According to a recent decision, the Hungarian government will set up a new anti-corruption authority in addition to reviving the anti-corruption task force which had existed before. The measure is aiming to access the EU recovery fund, but experts who have examined the corruption in the country are highly skeptical about such an institution bringing about any meaningful change in the Hungarian system. If the country were to join the European Public Prosecutor's Office, actual results could for sure be expected, but there is still no mention of this option. Whether the current gesture will be enough for the European Commission is an interesting question for sure.

Our institutions haven’t been functioning properly

"Just like in Western European countries, there still are modern anti-corruption institutions in Hungary, whose function would be to ensure that public spending provides a competitive environment for the market. But none of them perform their task satisfactorily," János István Tóth, director of Corruption Research Center Budapest (CRCB) told Telex.

Tóth pointed out that it may look like everything is in place in Hungary for fighting corruption: the legal framework is EU-compliant, the Public Procurement Authority, the Economic Competition Authority, the prosecution and the police are all functioning. But these cannot be considered autonomous institutions in Hungary, so they cannot be expected to be effective in countering the corruption that pervades all levels of public spending. The researcher argues that, on this basis, the creation of a new institution is not going to solve the problem.

József Péter Martin, executive director of Transparency International Hungary, is similarly sceptical. He told Telex:

“There hasn't been a truly independent monitoring institution in Hungary in the last 12 years. If this were to happen now, it would be a huge breakthrough that would go beyond the fight against corruption, but the chances of that happening are slim.”

However, given the logic of the system, it is very difficult to imagine that the new institution would not be another NER-authority: a pretend independent but actually controlled actor that does not go against the government on substantive cases. (note: The abbreviation NER is short for Nemzeti Együttműködés Rendszere, which means “System of National Cooperation”. The term was coined by the Orbán government in the early 2010s and was originally used to refer to changes within the government that were to be introduced. By now the term is used in colloquial Hungarian to refer to Fidesz’ governing elite and the oligarchs around it – all of whom are profiting from the system.)

"The state was gradually taken captive by the government elite and the informal business group around it, and by 2015 at the latest, the independence of all institutions except the courts had been lost. In this system, the establishment of a truly autonomous anti-corruption authority would represent a paradigm shift, which I do not expect," said József Péter Martin.

According to the Official Gazette, the draft for setting up the anti-corruption authority is to be prepared by Judit Varga, Sándor Pintér, Antal Rogán, Gergely Gulyás, Mihály Varga and Tibor Navracsics. In other words, a real ministerial super-team is working on the legislation, which could be a sign that they are taking the matter very seriously.

However, the credibility of the effort is somewhat undermined by the fact that several members of this group have already been suspected of misusing public funds. To say the least, the companies formerly owned by Sándor Pintér are thriving on state contracts and subsidies, and Antal Rogán and his circle have been linked to the multi-billion dollar business of resettlement bonds, among other things. His office is also responsible for the state contracts most suspicious of corruption, Judit Varga used state support ( so-called "CSOK" state funds families can apply for and which are to be used exclusively for a family's first home) for her holiday home (which she had allegedly wanted to move into), and her former state secretary Pál Völner is involved in a colossal case of bribery.

International standards don’t amount to much in Hungary

Putting aside the background for a moment, the question of how the new institution will actually work in practice remains. As for the prospective operating principles of the anti-corruption authority, the recent decision contains strong promises: ministers will have to develop the legislative framework and the institution itself "in consultation with the European Commission, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and other national and international organisations, in line with international standards and drawing on the best practices".

According István János Tóth this sounds good, but the framework would only have real meaning if the real independence of the institution could be guaranteed. József Péter Martin of Transparency International said that the only acceptable option in his opinion would be to appoint a person with a background of expertise who is far from Fidesz and other political circles. In Martin’s opinion, we will know what we can expect from the new authority once its head has been appointed.

But why do people matter so much against the institutional background? According to corruption experts, it is because the practices built up within the NER-system are of a very different nature compared to what the European anti-corruption framework was designed to do. A good example is the issue of single-bid public procurements, which the Hungarian government has specifically highlighted as one of the indicators to be improved. Hungary is not doing very well in this area within the EU, according to the latest figures

39 percent of public procurements above the EU monetary threshold are tendered by only one firm.

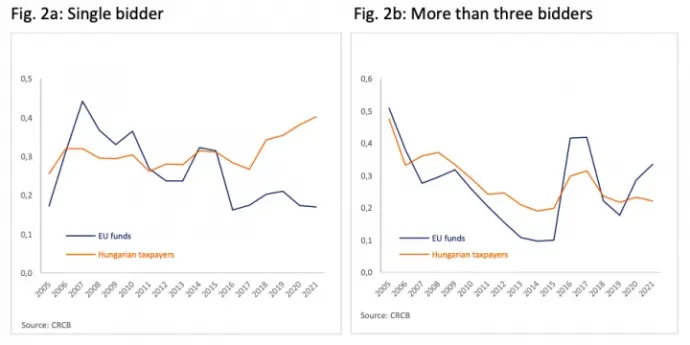

At the same time, the study conducted by CRCB (based on a different methodology) for the period between 2005-2021, found that since 2015 the gap between EU-funded and nationally funded public procurements has widened in this area. While competition has improved for EU tenders, the ratio of single-bid tenders has continued to increase in the case of Hungarian-funded tenders. This has been dubbed the Elios effect, because the phenomenon is attributed to Fidesz having burnt itself so badly over the Elios case that it no longer wants to confront the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) in an obvious manner.

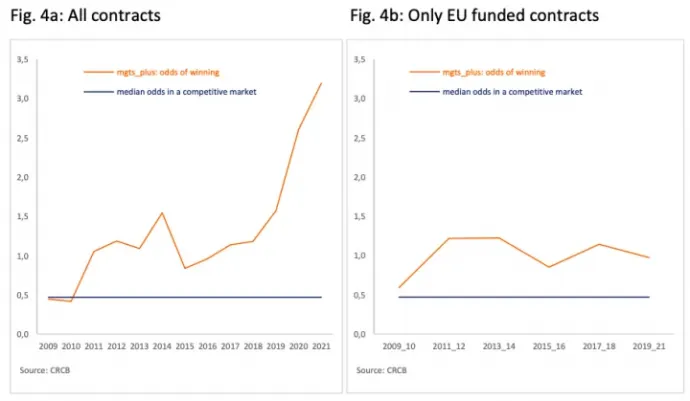

In the meantime, however, the chances of the companies identified as Fidesz's favorites winning all public contracts have not deteriorated, quite the opposite. "In a market-based system, a company's chances of winning a tender are 0.6 percent, while in Hungary the Mészáros Group has a winning rate of between 2 and 3, and Gyula Balásy's companies have a rate of over 70" István János Tóth told us.

Improving the indicator for single tender public procurements is therefore a good direction – in theory. However, according to József Péter Martin, it is not a panacea, as there are sectors where the market has been manipulated to such an extent that they are either partly or completely under the control of NER, thus excluding truly free competition. But even in the more market-based sectors, it will be difficult to restore confidence in the public procurement system, as it has been operating with marked cards for a long time.

In these cases, even multiple bidders are no guarantee for fair competition: János István Tóth and his team have specifically examined the phenomenon of losing bidders. In such cases, it is not only the winning firm and the contracting authority that are corrupt, but also the losing firms which are only bidding to keep up appearances. They are either set up to perform this function in the first place, or they are real companies that are later rewarded with subcontracting contracts for their involvement. For example, during its research, CRCB found a company that had competed in 72 public tenders in the reviewed period and lost 68 of them, which is statistically abnormal – it is quite likely to be the kind of company described above.

Internationally used corruption indicators were not designed to describe systems like the Hungarian one, János István Tóth explained. In the market economies where they have started using them, corruption is an occasional anomaly, while in Hungarian state practice it is part of the basic logic of the system. Therefore we cannot expect any structural change by lowering an indicator.

Why not the European Public Prosecutor’s Office?

In light of all this, it is not clear how convincing the European Commission will find the creation of a new authority. The stakes are high: the Hungarian government has been wrestling for months to finally access the 2,300 billion forints the country is supposed to be entitled to from the EU recovery fund, which – under the current economic situation – is needed even more urgently than before. Had the country submitted a proper plan last year, the money would have already been granted without any conditions, but it has now become subject to negotiations, with Tibor Navracsics, the Hungarian Minister managing the process. He said that if an agreement cannot be reached with the European Commission, it will not be because of the Hungarian government, and he has recently said that he no longer sees questions of policy as the obstacle to reaching an agreement, but rather political will.

One of the European Commission's requests is to decrease the level of corruption in Hungary, and the government's intention with the establishment of the anti-corruption authority is a gesture to this end. The only flaw is that there is actually no need to set up a domestic institution in this area.

There is an already existing EU body that could fulfill this role if the Hungarian government were serious about handing over control to an independent actor: the European Public Prosecutor's Office.

Joining the institution led by Laura Codruţa Kövesi has been rejected by the Hungarian government every time so far. The issue was present in the public discourse in Hungary for a long time because opposition MP Ákos Hadházy collected signatures in favour of joining (the target was one million, of which 680,000 were collected).

Accession to the European Public Prosecutor's Office cannot be imposed by the EU, as it falls under the category of so-called "enhanced cooperation", and nation states must decide for themselves whether to participate. Informally, however, the Commission could request of the Orbán government to do so during the negotiations for the recovery fund, Martin added. The intriguing question then is, whether they will instead accept the setting up of a Hungarian authority, which is likely to be less effective.

József Péter Martin predicts that this alone is unlikely to be enough, but as part of a larger package the EU may agree to this measure. István János Tóth believes that the impact of OLAF investigations has proven that the European institutions could effectively curb corruption in Hungary, and if it were to settle on this reform, the Commission would be revealing unpleasant facts about itself.

We have asked the Prime Minister's Office and the Ministry of Justice why, if they intend to entrust the area to a truly independent institution, the country should not join the European Public Prosecutor's Office. If we receive a reply, we will publish their answer.

If you enjoyed this analysis, and want to make sure not to miss similar ones about Hungary in the future, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!

The translation of this article was made possible by our cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.