Hidden hazards: Disinformation and waste in Hungary's battery boom

It was just another average day in Sándor’s life, just a new round between Komárom and Galgamácsa. The double-walled ADR big bags, (bags for transporting dangerous goods by road) were meticulously lined up in the back of the truck. He was transporting nearly 20 tonnes of hazardous waste, with the identification number EWC 060315*. On every trip he promised himself that next time he’d take his family to the Bear Shelter in Veresegyház, he knew the children would definitely enjoy it.

Gábor was not as lucky, as there was an accident on motorway M5, which meant he could only crawl along towards Szeged-Kiskundorozsma with the tanker transporting about 20,000 litres of hazardous waste (identification number EWC 161001*). The heatwave didn't make the slow traffic more tolerable, but what really overwhelmed him was the thought of having two more rounds ahead of him that week. He was hoping he wouldl have more luck next time, and finish the ride somewhat earlier. He was looking forward to kayaking on the shady side of the Danube Bend on his holiday.

Anita logged on to the real estate website again, but she knew exactly that since the phone didn't ring, there would be no message waiting for her there either. No one has even inquired about the house for sale (which was near an operating battery factory), even though she had already reduced the proposed price. It was once again painful to see that houses are no longer so easy to sell in this formerly attractive suburban area. There was nothing left to do but figure out what and where she could buy for her family if she lowered the price again and they were finally able to move.

Our characters and their names, thoughts and feelings are fictional, merely the figments of imagination. However, the code numbers for hazardous waste and locations are not. Unfortunately, these characters are completely absent from most pieces reporting about the battery factories in Hungary. Those who work in these factories and their suppliers, the officials who approve and oversee the factories’ construction, and those who finalise contracts with investors — these are the people in possession of this critical data. Without this information, it's nearly impossible to have a meaningful discussion about battery production and Hungary's role in the industry. This lack of data presents a significant challenge.

However, those who do have access to this data are generally bound by confidentiality and may not be interested in transparency or sharing the facts. There are a handful of researchers and experts who are bold enough to speak out publicly, and who thus expose themselves to the judgement that they are merely expressing a political opinion. And there is the majority who refrain from speaking up, either due to self-censorship and fear, or because they do not wish to express an opinion without data and facts.

Before being quick to pass judgement, it’s important to understand that these individuals do have an opinion. However, they hesitate to make professional statements because they feel it would merely be expressing personal views. Despite the fact that the growing number of battery factories is already having a significant environmental, social, and economic impact across the country—which will only continue to grow in the future—we’ve fostered an atmosphere that downplays these issues, framing them as merely local concerns. As one of the experts we interviewed put it, the consequences of today’s decisions will affect our grandchildren as well.

The withholding of crucial information, the decision-making being done without involving local communities, and the lack of transparency indicate that much of Hungarian society is being misled and subjected to disinformation about battery factories. This raises serious concerns about the sustainability of the industry and casts doubt on the overall green transition.

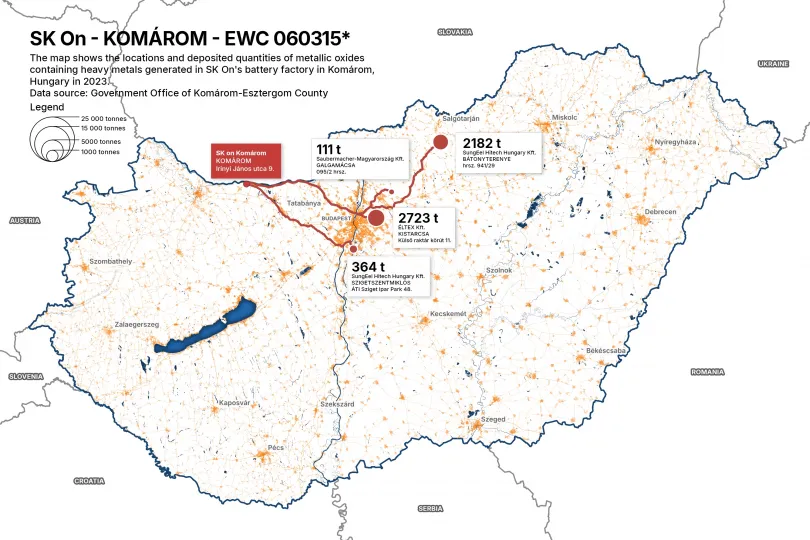

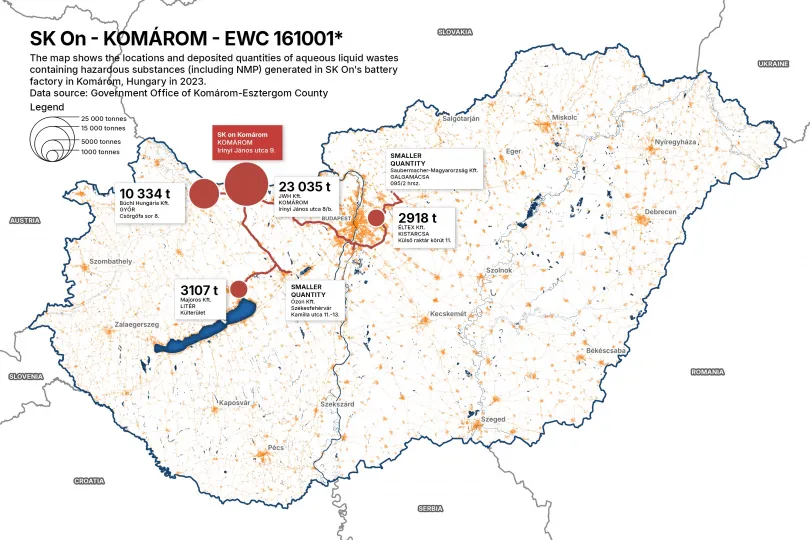

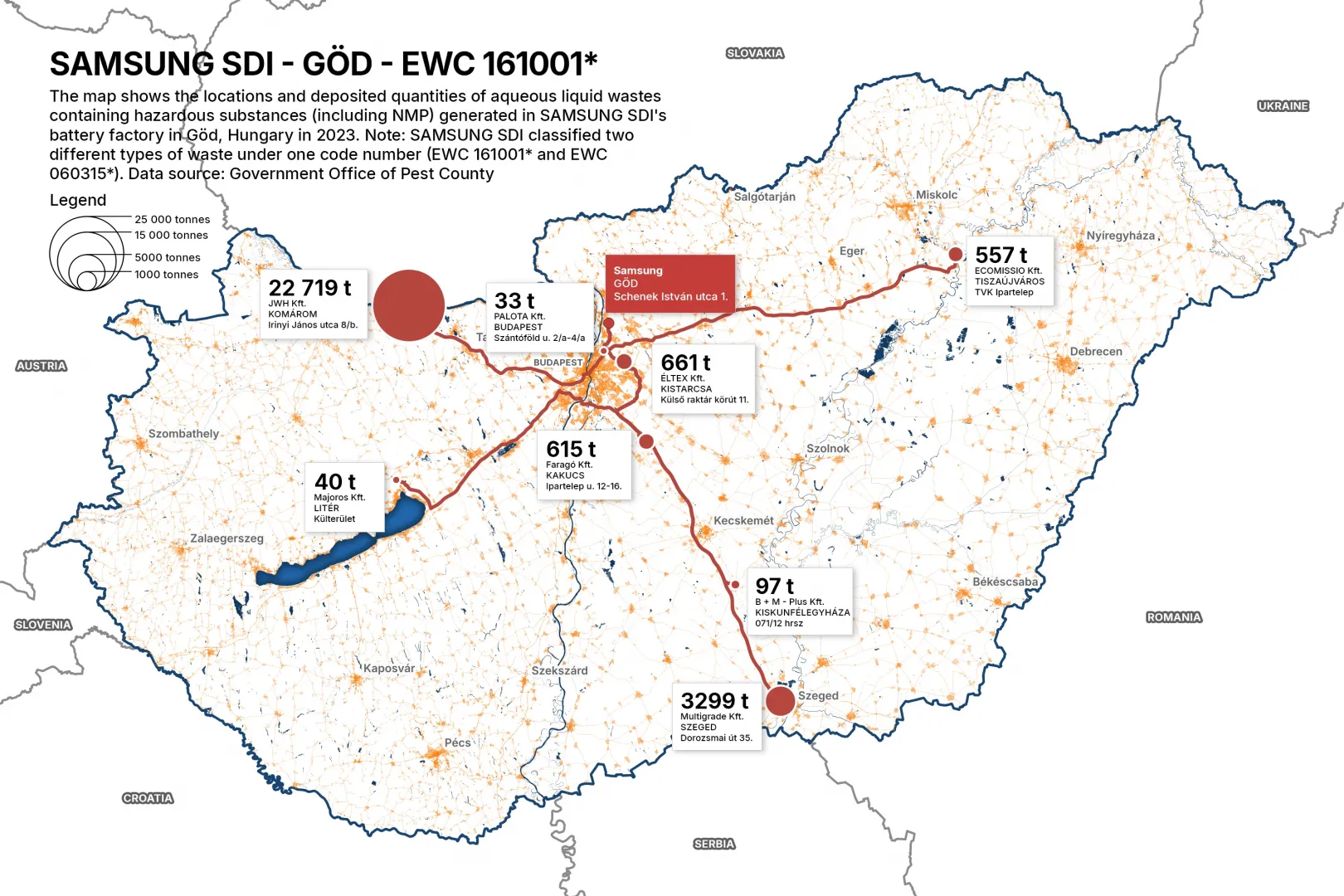

The only way to make a real difference is by gathering more data, analysing potential future outcomes through analogies and parallels, and understanding how we got here by uncovering past events. This article primarily focuses on the issue of hazardous waste, specifically EWC 060315* — metal oxide waste containing heavy metals — and EWC 161001* — aqueous liquid waste containing hazardous substances, commonly known as N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). Although this waste contains more than just NMP, it is the primary component produced by battery factories, so for simplicity’s sake, it will be referred to as NMP throughout the article.

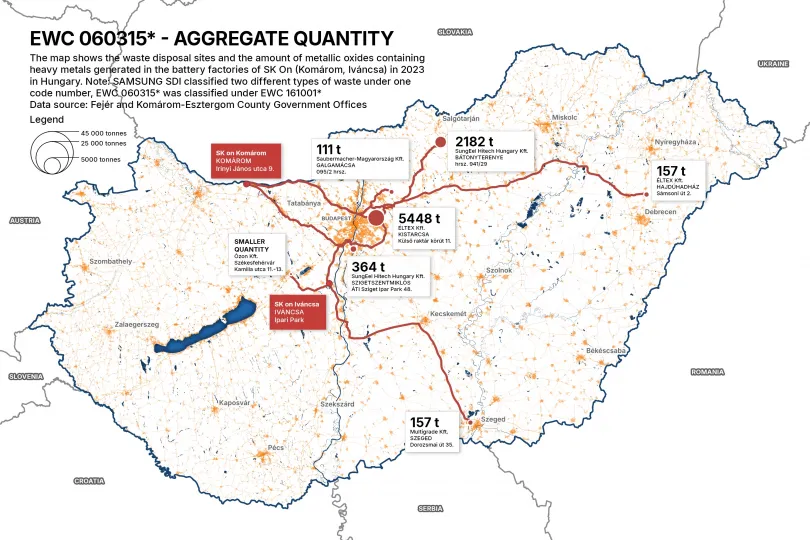

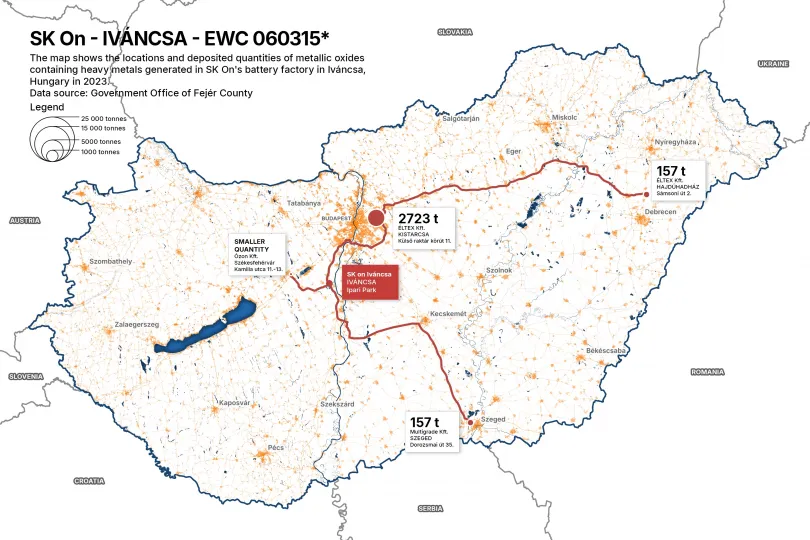

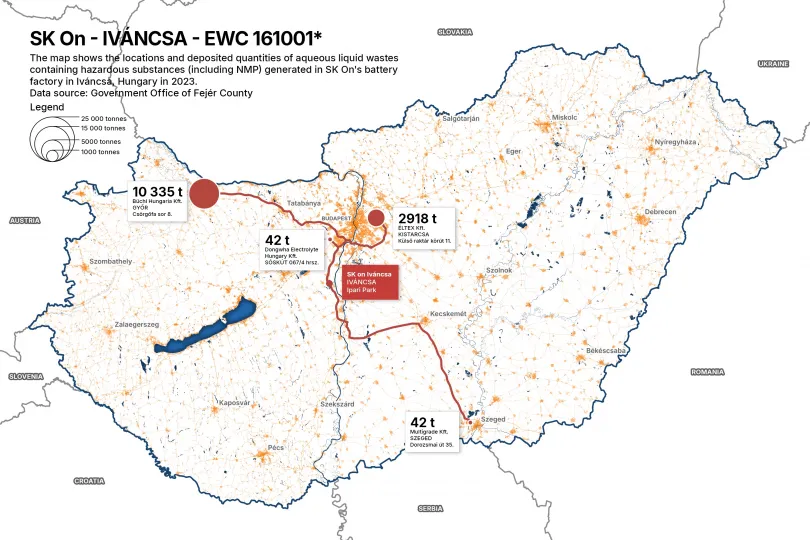

This investigation focuses on the already operating battery factories (Samsung SDI in Göd, SK in Iváncsa, and SK in Komárom). Using publicly available data which was requested as a matter of public interest and provided by county government offices, along with insights from our experts, we will reveal the amount of waste already being transported across the country, the routes used, and the potential environmental and health impacts—primarily through analogies.

This article will not examine the effects of these factories on water resources, energy consumption, air and noise pollution, or greenhouse gas emissions—not because they aren’t important, but due to limitations of space. We would have liked to explore the potential impact of these types of waste on soil, but soil science experts were hesitant to comment. We would like to extend special thanks to the experts who did agree to speak with us, given that it seems that in today’s Hungary, offering scientific and professional analyses can seem as a risky stance.

This article does not aim to determine whether lithium-ion battery production is inherently good or bad, but rather to discuss what actions we can take to improve the current situation.

Mapping the spread of toxic waste from battery factories across Hungary

It is not only during battery manufacturing that hazardous waste—such as heavy metals and NMP— are produced. What makes heavy metals and NMP particularly significant is their volume; given the expected increase in production once all planned and under-construction plants begin operations, it is almost certain that their quantities will rise significantly, even with the orders coming in from the global industry fluctuating.

A review of the publicly available national data on total emissions for both types of waste over the past eight years clearly shows how much these numbers have surged since the launch of domestic battery factories.

Since the public data for 2023 was not submitted to the National Environmental Information System (OKIR) by the statutory deadline, we reached out to the relevant county government offices (Fejér, Komárom, Pest) for environmental data of public interest. Below, we present the most recent data they provided, along with a map illustrating the amount of hazardous waste generated by the currently operating plants and the road transport routes used to move this waste (by tankers, lorries and trucks) within the country. While we don’t know the exact routes, the directions shown on the map were calculated using the Travel Time website.

We can see that the numbers grew at all three plants between 2021 and 2023, even though the SK battery factory in Iváncsa theoretically only did trial runs in 2023. Based on the authorisation documents, the Environmental Protection Department of the Hungarian Chamber of Engineers (MMK) estimated that – compared to 2023 – once it starts operating at maximum capacity, the Iváncsa factory could emit up to a hundred times more (129,250 tonnes per year) metal oxide waste (EWC 060315*) containing heavy metals. "The amount of the waste emitted during this time does not reflect trial runs, however under such a status, there are different rules and permits applicable to the plant," – added Zsófia Baloghné Gaál, environmental expert, vice president of the Environmental Protection Department of the MMK.

The fact that Samsung SDI has classified NMP and waste containing heavy metals under the same code number (EWC 161001*) in recent years, makes it difficult to disentangle the data. (It is important to point out that this data reflects what is reported and recorded by factories and authorities, but due to the increasing number of anomalies, we cannot say with a hundred percent certainty that it actually covers all generated waste of this type.)

The largest and only operational NMP regeneration plant in the country is JWH Ltd. in Komárom, so it's no surprise that a significant amount of waste is sent there. The plant's permit was not known for a long time but has now been submitted to the OKIR. Based on this information, we know that they are permitted to process 55,000 tonnes of waste annually. In 2023, they received nearly 48,000 tonnes of the two types of waste examined here, but they also accepted other waste types not covered in this article, so we cannot confirm whether they adhered to their permit. However, available documentation indicates that JWH plans to increase its processing capacity to 105,000 tonnes per year in the future, though no specific date for this has yet been provided.

Significant quantities of waste were also sent to Sóskút to the Dongwha Electrolyte Hungary Ltd., where the government plans to construct a processing plant. This is the settlement where the mayor had to be rescued under police escort following an outcry from the public at a hearing in January.

It appears that Hungary’s battery factories are already generating more hazardous waste than we are able to regenerate, neutralise, or recycle. The remaining waste not included in these processes is being disposed of in various locations – some of which are known and some which aren’t, and we have no information about the storage conditions or the future management of this hazardous waste..

Numbers and locations alone are meaningless. To make verifiable claims, we need consistent measurements, much more data, and greater transparency. It’s no surprise that public trust has almost completely eroded due to the industry's widespread secrecy, smoke screens, lack of data, and the deliberate withholding of information. This is detrimental both to the government’s re-industrialisation plans and to investors, as the public will likely also react with vehement rejection to the establishment of plants which do not produce hazardous waste but are somehow linked to battery factories. The primary concerns stem from the health risks linked to these factories and the hazardous waste they generate.

Dangerous or not? The legal framework vs. reality

There are at least two ways of determining whether a particular waste material is hazardous or non-hazardous. One is the legal approach, namely whether it is included in the Inventory of Wastes, and if yes, under which category. This may be changed at any time at the legislator's pleasure and discretion. For example, scrapped batteries (of which there still are a lot, but an especially significant amount was generated in the early production period) have been reclassified as non-hazardous waste. This distinction means that now they are subject to different – less stringent – rules.

And then there is reality. "Something is considered hazardous if it exhibits a hazardous quality. Being explosive, flammable, an irritant, carcinogenic – these are specific, measurable properties. If the waste exhibits these properties, it is hazardous. The question is when, under what conditions and at what dose it displays these characteristics. It is also a question of whether the waste contains substances or components which, because of their origin or concentration, pose a risk to health or the environment," says Pál Varga, chemical engineer, retired head of department of the (now former, no longer existing) National Inspectorate General for Environment, Nature and Water, chairman of the Environmental Protection Department of the Hungarian Hydrological Society, and former chairman of the Waste Classification Committee.

Since we lack continuous and publicly available data on this issue as well, reconstructing the type and extent of damage to health the battery factories have caused in Hungary will only be possible in the future by analysing Hungarian health data. "A workplace is examined retrospectively to see how workers were affected by exposure to toxic substances. The problem is that we will only receive data on battery factories later, which is too late. And we’re not talking about one or two substances, but about a dozen," said Béla Darvas, ecotoxicologist, doctor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS), chairman of the Hungarian Ecotoxicology Society. "Tumours caused by different compounds can take a decade to develop, they don’t appear after a month of factory work. People are not afraid of such exposure because the consequences are remote, it’s a bit like with cigarettes."

Factory workers and other personnel handling hazardous waste face the greatest health risks. However, due to the authorization process not ensuring adequate protective distances, residents in Göd, for instance, are also significantly impacted. Citing the ongoing lack of data and measurements, Béla Darvas is concerned that there are no guarantees these toxic substances will remain contained and not mix with domestic wastewater. While continuous data collection and monitoring could help, the monitoring well in Göd was buried with the knowledge and approval of the Hungarian authorities. "It’s nonsense, it’s no longer a professional matter," said Pál Varga.

While Tesla is already experimenting with battery cells that require little or no NMP and promises mass production this year, this is not yet the reality for large-scale production, particularly not in Hungary. According to Darvas, Mitsubishi has previously boasted about achieving an impressive 95 percent recovery rate for NMP at its plants; however, since this figure is based on self-reporting, it should be viewed with scepticism. Furthermore, given the volume of production, even a 5 percent NMP emission could be significant, especially once the plants currently being planned or under construction begin operations.

"The dose makes it poisonous. NMP does not accumulate; the question is for how long and to what extent someone has been exposed. If it only happened once, it is likely that there is no health risk. If exposure is continuous and chronic, then that presents a health risk, even though it is not an accumulative type of poisoning," added Darvas.

NMP does not enter the food chain, but nickel-manganese and heavy metal waste does, and can accumulate there, just like in living organisms. Lithium acts the same: As an example, Darvas brings up the lithium pollution in the vicinity of Shanghai, where the substance accumulated in the drinking water, and it was only later linked to a noticeable increase in heart muscle weakness among the population. In the case of heavy metal waste, some dust is sure to escape during the process of filling the bags, so soil and water should be constantly monitored. "Annual check-ups cannot be taken seriously, there should be regular measurements done at least every week or every two weeks, and immediately after accidents, of which there are many," says Darvas.

Stringent threshold limit values can help, but they do not solve the problem

Unfortunately, even if strict emission limits and threshold limit values (or TLV’s) were established for battery production in Hungary and adhered to, it would not be a perfect solution to the environmental problems.

"If we take a look at the environmental authorisation of CATL, the battery factory in Iváncsa, or the cathode factory planned at Ács, we see that the NMP limit will be the value the factory emits for the first time. This is insane. Why would it be the factory’s interest to set strict limits for itself?" asked Andrea Éltető, economist, senior research associate at the HUN-REN KRTK Institute of World Economics. Accordingly, there is no uniform limit value for example for NMP emissions in Hungary, because it always depends on the combination of the respective technology and the solvents used, added Zsófia Baloghné Gaál, vice president of the MMK Environmental Protection Department. But if there were, that alone would not be a definitive solution.

"The stringent limit value sounds good, but at such a high volume there are still brutal amounts generated. That’s why it’s not the limit that counts, but the load capacity. For example, how much and what kind of waste can be discharged into the Danube? A limit of 1 mg/m3 may be appropriate for a small plant, but not for such large factories. So it is possible that we are poisoning the Danube. The limit value alone only masks the responsibility, because the manufacturer can say that they have complied with it," says Dénes Parragh, biologist, president of the MMK Environmental Protection Department. "Whether 5 kilos or 5 tonnes of heavy metal waste enters the Danube every year makes quite a difference" he said, referring to the figures related to the scale-up of the Iváncsa plant.

Waning professionalism, prevailing legal attitude and an unprepared administration

In light of the rapidly mounting environmental issues, the question arises: was the professional and official administration prepared to support and accommodate the entire battery industry in Hungary? According to the experts consulted, the answer is no. This is not only due to a lack of intention but also because the process erosion that began before 2010 has only accelerated since then.

"It’s important to realise that the more complex a question is, the more professionals and experts are needed, but there is less time devoted to this and the demand is decreasing, while the environmental issues are very diverse. These problems cannot be swept under the carpet, because the clock of these environmental issues will continue ticking there too," Varga said to support the fact that over the years there has been a steady shift from a professional perspective and approach to a legal perspective. From what should be done to what can be done. He also said that during the years he had spent as head of department at the former Environmental Inspectorate General, the two parties (expert and legal) had the same weight, but this has now changed completely.

"Our profession is terribly distressed by the imbalance between the professional and the legal perspectives. We are horrified. We cannot take action, but we refuse to make baseless claims without data. Nowadays, in the world of rapid political decisions, we are seen as a nuisance. Even though we wouldn’t need to learn things from scratch, because back in the day we were able to escape from the similar thinking of the socialist era. Parts of our environmental legislation were already EU-compliant in the nineties, long before our accession," says Varga.

However, it’s not just politicians who can impede thorough expert investigations. Many Hungarian voters also believe that the industrialization of the country and the construction of new factories are essential for development and prosperity, and they worry that expert investigations could ultimately obstruct this progress. This mindset also strengthens the politicians involved in these matters.

"In the preliminary phase, it must be assessed whether the planned investment will have a significant impact. When assessing the significance of the impact, consideration should be given to the nature and scale of the particular investment, as well as the sensitivity and use of the area concerned. It is after these that the authority will then decide whether an additional detailed impact assessment should be carried out. It is clear that the battery factories that are already in operation are having a significant impact on the environment," added Varga. However, in some cases (e.g. Samsung SDI), the authorities have decided that no detailed assessment is required.

Even if there were a miraculous change in attitude in Hungary, we would still face singificant challenges due to the decreasing number of specialists. The Budapest University of Technology and Economics, where Varga still teaches as a retired lecturer, has discontinued its postgraduate training in impact assessment. Additionally, many waste experts are leaving for opportunities abroad because the profession is no longer appealing to them in Hungary. This highlights the significant work we need to do in terms of training and recruitment.

According to Dénes Parragh, problems and deficiencies related to battery factories have directed attention to long-standing cumulative problems: such as the lack of specialists in the state administration, the elimination of independent environmental monitoring bodies, the introduction of government agencies, the dismantling of regulatory laboratories that operate alongside monitoring bodies and the elimination of background institutions (e.g. the Environmental Protection Institute, the Water Research Institute (VITUKI)). For instance, the professional teams at the supporting and background institutions would have been able to assist in gathering the best practices from abroad. This, alongside the strategic review (which wasn’t carried out), could have aided the authorities in preparing to develop a protocol for authorization conditions for a highly complex and rapidly evolving industry.

No strategic environmental study was conducted. Such a study would have not only identified specific environmental issues but would have also examined the related infrastructure conditions, such as:

- The ability to meet high electricity and natural gas demands,

- Ensuring sufficient (high) water supply,

- Special wastewater treatment requirements,

- Infrastructure and environmental concerns associated with transporting large quantities of raw materials, finished products, and waste.

Considering the significant levels of air and noise pollution of these factories, along with the high volume of vehicle traffic, it would have been prudent to establish safety distances from residential areas. An examination of the locations reveals that nearly all of them are situated close to residential neighbourhoods.

“This not only raises environmental and public health concerns but is also a significant issue from a disaster management perspective,” Parragh responded to our inquiry. He noted that it was a serious indication of problems when high-level officials from the highly hierarchical and strict (as he described it, military-like) state Water Management Directorate expressed some criticism during the approval process for the CATL investment in Debrecen. He specifically referenced Dániel Kincses, the former director of TIVIZIG, who was removed from his position as a result. Despite this, many of Kincses' recommendations have been implemented since then.

Governmental priority investments, of which there are more and more in the country, have been criticised for a long time. An initiative for a national referendum to change the system is currently underway, but its success – i.e. whether it will receive the necessary two hundred thousand signatures – is highly questionable. A priority investment status exempts the central government and the investor from many procedures that are otherwise mandatory. At the same time, Parragh believes it is a misconception that environmental permits are not required for priority investments. These investments are also subject to the same procedural rules, except the procedure takes less time, which imposes an extra burden on the authorities. The main difference is that if a permit issued in such procedures is challenged in court, the investment does not need to be suspended until a court decision is reached.

The priority status is a bigger problem in terms of the location of the investments, as it can be used to designate the plant site against the will of the local government and the residents. "It is unacceptable to make decisions against local residents on matters affecting their place of residence, and such decisions cannot be taken without their consent. Especially in the case of investments of this scale and risk."

According to Parragh, the government's heavy-handed approach — focused on authority and control rather than persuasion, negotiation, and explanation — can be effective in the short term by accelerating progress. However, in the long run, this approach will struggle to address and resolve complex issues. And judging by the numbers, that long run is closer than we might think.

According to our anonymous government sources, there is no uniform optimism and enthusiasm for battery factories within the government and management circles either, even though little of this is visible to the public. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, led by Péter Szijjártó, along with the National Investment Agency (HIPA), headed by István Joó, have been leading efforts to attract investors to Hungary and finalise contracts. County governors involved have also been actively facilitating these projects. The role of the Hungarian Battery Association, led by Péter Kaderják, in all of this process remains unclear. We sought to interview him for this article, and while he initially seemed open to the idea, we were unable to reach him through any channel and received no response to our questions.

According to our governmental sources, among those less enthusiastic about these projects are Energy Minister Csaba Lantos and MOL CEO Zsolt Hernádi. However, at the end of last year, the conservative think tank (filled with former high-level state and government people) Green21 also published a 12-point list of recommendations regarding battery factories. The founders of the organisation include former Head of State János Áder, former minister László Palkovics, several former state secretaries and deputy state secretaries, such as Péter Kaderják, and Dávid Vitézy.

According to the recommendation, battery factories in Hungary cannot be subject to less stringent environmental regulations than those in force in Germany. Transparency and social awareness are also important: "It must be ensured that information related to the sustainability of battery industry activities is systematically collected, analysed and made available to citizens. This requires the establishment of the Public Environmental Monitoring and Laboratory Network and the Public Battery Competence Centre." The seventh proposal goes even further: "When implementing investments in the battery industry, special attention must be paid to involving local society at all stages of the decision-making process. The expected developments and the ways in which local communities are expected to benefit from the investments (tax revenues, jobs,et), as well as what plans the developer, the central as well as local governments have to mitigate any risks associated with the projects should be clearly communicated."

It’s clear that multiple efforts have been made to persuade the government to reconsider its current battery factory policy. The Environmental Protection Department of the Hungarian Chamber of Engineers has even prepared a specialised guide for experts and officials involved in the process. "Having experienced the difficulties in preparing authorisation documents and carrying out regulatory procedures, the Environmental Protection Department of the MMK has repeatedly consulted the deputy state secretary responsible for environmental protection at the Ministry of Energy. To date, this cooperation is considered useful and well-functioning, although the results have often not been reflected in the permits issued by the counties," said Dénes Parragh.

Will the Chinese do better?

Nearly all the experts we interviewed believe that the Hungarian government's approach to negotiations with battery manufacturers has been largely characterised by an urgency to bring them into the country. "Working capital is being used to compensate for non-refundable but frozen EU subsidies, but this is an extremely bad direction and makes no economic sense, as profits are unlikely to stay in the country. We will be lucky if they invest part of it here at all, but it is more likely that they will take it out and use it for their own companies at home or in other countries," Ágnes Szunomár, an economist and habilitated associate professor at Corvinus University in Budapest opined.

In her view, the opening to China did not begin in 2010 at all, but before that, already under the Medgyessy government (2002-2004), even though the “Eastern Opening” only became the government’s official strategy after 2010. Today, there has been a global decline in working capital investment, while the Chinese continue to invest actively, but many countries are reluctant to welcome this due to perceived economic and security risks.

All the battery factories currently operating in Hungary are subsidiaries of South Korean parent companies. According to our experts, these companies also have (and create) a lot of problems globally when it comes to safety or environmental regulations. However, Korean firms have gained such a competitive edge in innovation in recent years that they have managed to continue operations with minimal scandals (despite the issues), largely because they are in high demand and there has been little competition.

Szunomár said this could change – positively – with the appearance of CATL in Hungary. "Managing reputational risk is important for the Chinese, they simply cannot afford the fiascos and scandals we have seen with South Korean companies so far. China’s investment in the battery industry is also important because of its demonstrative effect, to prove that the Chinese industry is able to compete with European brands."

“It’s also important to note that Chinese companies, which are closely linked to the Chinese state in one way or another, don’t operate solely with a capitalist or profit-driven mindset. They plan 50–100 years ahead, viewing their efforts as part of a global race. This long-term strategy is how they are establishing a presence in Europe through Hungary,” added Zoltán Fleck, a law sociologist and university professor at ELTE’s Faculty of Law.

However, according to Ágnes Szunomár, if we do not negotiate more firmly, the Chinese are unlikely to bring some of their RDI departments to Hungary along with the fortune cookie machines they put out at events. Although CATL receives substantial state funding, – previously reported as 800 million euros – we do not know whether the government has asked for anything in return.

Not all of the experts we asked shared positive expectations about the CATL factory. "The problem is that even if CATL adheres to all limits and rules, it will still have a significant environmental impact, simply because of its size and planned volume. The amount of water vapour emitted alone will be able to change the microclimate in the Debrecen area," said Andrea Éltető. According to the expert, the water contamination from Halms, the Chinese battery supplier in Debrecen, which was covered up for months, is not a good sign either.

Although the Chinese submitted their NMP emission modification request to the government office in the summer, and have tightened the limits for one point source, in case of such a volume, as Dénes Parragh said, the emission limit alone does not provide protection, and it is important to determine the load capacity, i.e. the emission value (air pollution level, the concentration of pollutants in the air near the ground) based on the emissions of all plants, and to enforce them.

As Parragh said, the unclear legal regulation of airborne limits for NMPs, which are harmful to foetuses, and several official limit setting procedures that are not really legal, would deserve a separate study. The situation regarding the planned regeneration of the aqueous solution of NMP recovered during production is not reassuring either. Since CATL only plans to build its own NMP regeneration plant in the second phase in 2025, large quantities of hazardous waste (more than 50,000 cubic metres) are expected to be regenerated by an external company located several hundred kilometres away ( this could currently be JWH). Having tankers travel on public roads poses a significant disaster risk, with another problem being that we have even less insight into the operation of waste recycling and disposal companies than we do into battery factories. Their authorisation and inspection procedures show even greater shortcomings.

Some of these we will find out about – while we will only find out about others if someone reveals them. Zsuzsa Bodnár and the civil watchdog online newspaper Átlátszó have been persistently following details about heaps of hazardous waste being stored in dilapidated agricultural buildings or former Soviet barracks – illegally, without complying with safety regulations in Abasár, Iklad and Mohora (among others).

Could we really become a lithium superpower?

In 2022, compared to other regions of the world, the European Union had the highest rate of circular material use —11.5 percent, according to the 2023 report of the European Environment Agency. While that might sound promising, the reality is that progress has stagnated since 2010, with no significant increase in circular material usage, despite the EU’s high level of vulnerability in this area.

The EU relies heavily on imports of nearly all types of raw materials, from hydrocarbons (fossil fuels) to rare-earth metals, without which its economy would come to a standstill. Russian aggression in Ukraine has forced the bloc to work towards reducing, and eventually eliminating its dependence on Russian fossil fuels. The Critical Raw Materials (CRM) Act aims to mitigate these risks by diversifying the supply of key materials like nickel, cobalt, and lithium (used in battery production), increasing circularity, and supporting research and innovation in resource efficiency and the development of substitute materials.

The new EU Batteries Regulation, adopted last summer, emphasises that decarbonizing the energy sector necessitates energy storage solutions, such as batteries. This means we must maximise the extraction, retention, and recycling of valuable raw materials from all types of batteries that have reached the end of their life cycle. Consequently, the regulation outlines requirements for end-of-life batteries, including collection targets, material recovery goals, and extended producer responsibility.

"This is a significant change because previously there were separate rules for waste, for scrap and for end-of-life batteries. The latter will no longer be the responsibility of the manufacturer in general, but in an extended way: they will have to take them back, process them, or finance the associated tasks if they are carried out by someone else," said Pál Varga, who also stated that due to the production volume and the future return flow of batteries at the end of their life cycle – which will be migrated back to Hungary in large numbers – we may even become a lithium superpower.

Of course, only if we are prepared for it, as currently, we aren’t even able to deal properly with the hazardous waste we produce today. Béla Darvas also said that technological readiness would also be necessary if we are planning with this industry for the long term, because it would essentially mean that the country would have its own mine. In his opinion, it was precisely the new EU regulation adopted last year that would have offered the government the opportunity to renegotiate the contractual terms with existing companies and new investors. We do not know if this has happened or was intended at all.

Naturally, the situation is not that simple, because processing is just as polluting and dangerous as production itself – if not more. “How can we expect to have enough recycling plants when there’s already such widespread rejection and fear towards the industry?”, Andrea Éltető said, pointing to the lack of social support and trust.

However, as expired batteries are returned over time, the question arises: will Hungary become merely a massive storage site for waste, or will it address the issue differently? The government likely recognised this problem, which is why Minister for National Economy Márton Nagy recently announced that the MOL Group is actively exploring solutions in this area.

Government estimates we received indicate that the total water demand for lithium-ion cell production could reach a staggering 40,000 cubic meters per day, depending on the technology used. This makes innovation and the utilisation of treated wastewater crucial. According to our government sources, potential solutions are being explored with Brinergy in Spain and Hidrofilt in Hungary. Former Head of State János Áder is also advocating for the latter company.

As Dénes Parragh stated, Hungary's ambition to enter the battery industry and electromobility wasn’t inherently a bad idea; the issue lies in the proportions. "Are we sure we want to have so many factories and such a large production volume in a country where the necessary resources are not available? Hungary has (or could have) strengths in the food, pharmaceutical and IT industries for example. The added value is much higher in these areas, while the energy requirements are significantly lower, just like the environmental impacts. And these would probably not require a large number of foreign workers."

Andrea Éltető is also concerned about the lack of thorough thinking: "First we got the button, now we’re looking for the coat. We have not thought carefully about what this industry entails, and now we are rushing to catch up."

The opportunities and impossibilities of protecting ourselves

Given the existing and growing pile of problems, what can we do differently now, and what actions can individuals take until the situation improves significantly? As previously mentioned, rebuilding social trust — if it’s even possible — would benefit both the government and the investors.

Achieving this, however, would require radical changes in our current approaches to authorisation, operations, transparency, and dialogue with local communities. "We should be pro-Hungarian, not against the battery industry itself" said Zsófia Baloghné Gaál, referring to the disproportion between what these factories demand and what the country and local communities see in return.

Our experts suggest that we should advocate for investors to bring the best available technological solutions to Hungary, minimising environmental impact and resource consumption as much as possible. This would likely require additional investment and would lower profits for the companies in question, while negotiating these terms would be the government's responsibility.

We need consistent, reliable measurements, and this data must be made public. Facilities should operate within a truly closed system, isolating them as much as possible from public infrastructure. The costs of these measures, including ongoing monitoring, could be funded wholly or partially by the investors, with oversight and enforcement handled by the authorities.

While the experts we interviewed believe that the regulatory environment was fundamentally well-suited for managing the growth of the industry, it is crucial to keep legislation up to date in this rapidly changing field. This includes clarifying what is included on the waste inventory and under which categories, to prevent investors from exploiting any gaps. The authorities must available sanctions, whether that means halting production or prohibiting certain activities. Additionally, a significant increase in penalties is necessary, as the current fines lack a dissuasive effect; plants often pay these fines and continue operating as before.

"All stakeholders need to adopt a serious approach to the scale and seriousness of the problem. The first step is to actually face what is happening. What we are seeing instead is smoke screening and the creation of political and economic issues. This raises the question of who should be the one addressing these complex, challenging, and varied issues: the politician, the economist, or the expert?" added Pál Varga.

As recommended by the conservative think tank Green21, it is crucial to collaborate with local communities, foster dialogue, and genuinely share the benefits generated by the factories. Currently, the opposite is true. The law fails to offer adequate protection; for instance, the Samsung factory in Göd was supposed to partially shut down, yet this did not occur despite a court ruling.

This process is not only a feature of battery factories. In 2018, in Madocsa, near Paks, via a local referendum and in full agreement with the population, the local government overwhelmingly rejected the opening of a gravel pit on the outskirts of the village. With a participation rate of almost 80 percent, 98 percent said no to the investment. However, with the active support of the authority, the investor tried to continue the authorisation process for a long time as if nothing had happened. According to Dénes Parragh, such disregard for local self-determination is unacceptable and unlawful on the part of the authorities.

But those who expect that Brussels will save Hungarians from themselves (and from current governmental policies) are also chasing dreams. "The enforcement of environmental rules and the setting of penalties are all competences of the member states, so we can sabotage ourselves in a completely sovereign way," Ágnes Szunomár commented. Especially because the EU is also in dire need of batteries. It is no coincidence that German Chancellor Olaf Scholz even travelledto Serbia this summer, to show his support for lithium mining.

According to Andrea Éltető, the Ministry of Energy's July amendment to the law, which requires all companies involved in battery production to have an environmental permit, is an irrelevant procedure that resembles greenwashing techniques. "On the one hand, until now most of them should have had such a permit in accordance with the applicable Hungarian legislation and even an EU directive of 2011, and on the other hand, until now such a permit has always been granted as a formality to companies (even if waste management, wastewater treatment, air pollution monitoring could not be operated properly, see Samsung SDI)". Zsófia Baloghné Gaál also considers the amendment to the legislation similarly flawed and unnecessary, saying that where a certain quantity of e.g. NMP-type solvents has been exceeded, an environmental impact assessment would have been required (which was not the case). As a result, all assembly plants that do not use such hazardous materials, but are in some way connected to the industrial value chain, are also subject to this legislation.

So what can be done? Our experts, and even government sources, say that the only thing left is to apply political pressure. This brings us back to the issue raised at the beginning of the article: without data and transparency, meaningful professional dialogue is impossible. Many fear the stigma associated with expressing anti-government sentiments. But the voters who see the problems with battery factories, but do not want to be labelled as opposition sympathisers due to their opinions will also be hesitant to speak up.

For a while this situation is extremely favourable for the government, but only until the first serious problems emerge or when the general public becomes aware of them. It is true for any government: it is no coincidence that in Serbia, the Vučić government has been dismissing the persistent and increasingly angry waves of protests as nothing more than simple anti-government demonstrations. Earlier, he had added statements, perhaps familiar in Hungary, that the protesters were planning a coup against him on behalf of an unnamed Western country. He told journalists they had received this information through Russian intelligence sources. A good example of the very complicated domestic political situation in Serbia is the fact that some in the opposition even mix the protests against lithium mining with anti-EU sentiment, as they feel that it serves primarily the purposes of the European Union. Nikola Zdravković, head and editor of the Serbian scientific climate change and awareness-raising platform Klima101, said that there is incredible tension around the issue, and he isn’t ruling out the possibility of violence from the population if Rio Tinto starts mining, which he says will almost certainly happen.

It is unlikely that positive, systemic changes in battery industry policy will occur spontaneously in Hungary. According to our experts, the government — accustomed to a forceful approach — along with an already weakened administration that shifted its focus from professional expertise to legal matters, and the greater lobbying power that suppresses existing concerns within the government, can only undergo substantial change if there are political consequences for rule violations by these (and future) battery factories. Environmental impacts are already being felt, social issues are on the horizon, and potential health problems will emerge later.

In order to slow down the environmental and climate crisis and to adhere to the climate target set out in the Paris Agreement – which Hungary has also enacted in law – we must, among other things, almost completely phase out fossil fuels from the energy sector as soon as possible. According to all major international think tanks and organisations, be it the International Energy Agency (IEA) or the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), electrification on an unprecedented scale is key to this. With little exaggeration, almost our entire lives will be powered by electricity, optimally produced from renewable energy sources.

To balance production and consumption, energy storage and therefore batteries are currently essential. The price of which, according to IEA calculations, has fallen at one of the fastest rates among energy technologies over the last 13 years: from USD 1400/kWh in 2010 to a tenth of that, to USD 140/kWh in 2023. This can and should be welcomed, but we are paying or will pay a high environmental and social price for today’s cheap batteries both in Hungary and globally.

Shifting the environmental burden and human suffering back and forth in space and time will not solve the problem, nor will it provide solace knowing that other countries are managing the industry even worse, incurring greater environmental and social costs. Relying solely on waste figures — without analysing water and energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and air and noise pollution — indicates that this is already a national issue in Hungary, and it is poised to escalate.

Neglecting environmental and social justice issues can fundamentally undermine not only the Hungarian government’s re-industrialisation policy, but also, in the absence of public trust, the climate targets, which are in the interest of all of us. Otherwise – to quote and complement the opening speech of UN Secretary-General António Guterres from COP27 – it will make no difference whether we are driving a vehicle with a combustion engine or one powered by an electric drivetrain when we are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator.

—

In the second part of our analysis, we will examine the expected social impacts of the industry and the issue of guest workers.

We would like to thank our experts, Zsófia Baloghné Gaál, Béla Darvas, Andrea Éltető, Zoltán Fleck, Nikola Zdravković, Dénes Parragh, Ágnes Szunomár and Pál Varga, for helping us with their knowledge and insights in the creation of this analysis.

The map data visualisations were created by Mihály Minkó.

The article was produced with the support of the Heinrich Böll Foundation’s Climate Disinformation Fellowship.