With the headlines dominated by epidemiological data and news of the vaccine rollout, there is not much light on how marginalized groups are affected by the pandemic. Hungary's segregated Roma communities living below the poverty line are at a disadvantage in multiple aspects.

The housing quality in Roma estates is dismal; households are overcrowded, allowing the virus to spread like wildfire in these closed communities. In many places, there is no city water or sewage system.

- On average, people living in these communities have poorer health due to their social circumstances; they live shorter lives than the majority society, smoking, alcoholism, and obesity are more prevalent, while they have worse access to healthcare.

- Poor education, a lack of information, and a mistrust of the healthcare system make these communities fertile grounds for misinformation and conspiracy theories, creating negative attitudes towards vaccination. If someone does want to get vaccinated, they have little access to information on how and where they can do so.

- Many lost their jobs due to the pandemic, a majority of students were left out of digital education, which only increased the existing inequalities.

It is no accident that the European Commission called attention to their situation in a statement published on International Roma Day:

"We must do everything possible to address not only the current crisis affecting them but also to bring real change on the ground."

In a recent report by Reuters, Aladár Horváth, the Chairman of the Roma Parliamentary Association, said that people in the ghettoes do not have money for medication, and even basic hygiene conditions are sometimes lacking. According to what he heard, the coronavirus tore through Roma communities in small towns, Budapest, and the estates as well. "Our people are dropping like flies," said the Roma rights advocate who recently lost his 35-year-old nephew.

According to statistics, there are 1300 segregates inhabited mainly by Roma people in Hungary. The population of these segregated communities is around 200,000 people, 2.8 per cent of Hungary's population.

An outbreak in a Roma estate can have catastrophic consequences

"I haven't really heard about any families in Nagykálló where nobody got infected. At one point during March, I had twelve relatives in hospital,"

A Roma rights activist based in Nagykálló, Zsanett Bitó-Balogh, told Telex. She didn't see many cases during the first and second waves, but this spring, the pandemic exploded throughout her community.

How Covid-19 affects people varies widely by individuals, but as she said, local general practitioners were unaware of their patients' pre-existing illnesses in many cases. The activist says there are three reasons behind this. First, in poverty-stricken villages, a healthy diet is next to impossible due to a lack of money; people rarely eat fruits and vegetables. Secondly, work and household chores often take preference over a visit to the doctor, even in case of severe symptoms, so serious diseases are diagnosed late, if at all. But there is also a fear in Romas: Bitó-Balogh says they are often wary of doctors and hospitals, "they are afraid that once they go in, they would never come back out."

"I've been parroting this since the start of the first wave; An outbreak in a Roma estate will have catastrophic consequences. Sadly, I was proven correct; many people around me have died in recent months."

In the segregates in Bag and Dány in Pest county, where the BAGázs Association is active, the first outbrakes also appeared at the beginning of the third wave. Emőke Both, a founder of the group, told Telex that ever since the beginning of the pandemic, they were worried that the coronavirus could have dire consequences once it started infecting families of Dány and Bag. Luckily, most who caught the disease eventually recovered, although there were some severe cases and deaths just like anywhere else in the country. Working with local GPs, the municipalities were doing their best to inform the locals about the preventive measures and the dangers of the pandemic. They were amongst the first to feel the economic effects; many people lost their jobs in the autumn and ended up in difficult financial situations.

You get your results at the post office

What was shocking is how difficult it was to organize the testing. In some cases, it took weeks for an ambulance to finally show up to test for suspected infections; in others, they only tested a single member of a family despite others also producing symptoms. An added difficulty in the estates is that not all households have phones, making it next to impossible to notify people about when the paramedics come to take the sample. They tried to solve this by using the numbers of neighbours or employees of BAGázs.

Another absurdity is that since many people do not have e-mail addresses, they had to pick up their quarantine enforcement orders at the local post office, as letters are not delivered to the segregates. Emőke Both said:

"You could clearly see that the system was unprepared to deal with people without phone numbers or e-mail addresses."

At the same time, some were reluctant to get tested despite showing symptoms; they were afraid that they would not be able to work or lose their jobs once they are quarantined, jeopardizing their entire families' livelihood.

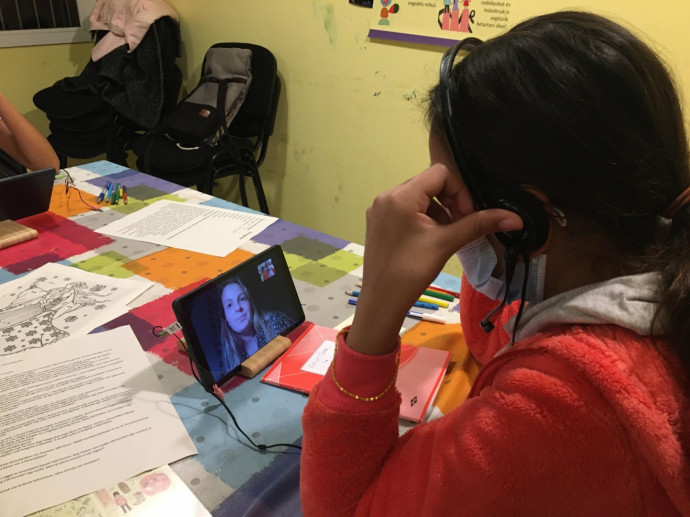

Digital education was another big issue, as BAGázs experienced, and distributing the necessary devices among families in need hardly remedied this. Disadvantaged children have a tough time participating in online classes, and their parents cannot offer much help either, especially if they have to go to work. "In families where the parents cannot read or write, managing online education platforms is no mundane task," Both explained. Volunteers of BAGázs tutor these children 3-4 times a week, however, they cannot replace in-person education, and in the past year, these children have fallen behind irreparably.

Even though the government made internet access free of charge for students and teachers, this opportunity fails to help those who need it the most, given that cable services are often unavailable in their homes. If anything, people in poor towns tend to use mobile data connection, but that is not subsidized.

Unemployment is raging

Krisztina Tasi, a local program coordinator of the Hungarian Charity Service of the Order of Malta, works as a psychologist and social worker in Tiszabő, a small village inhabited by roughly 2000 people. The coronavirus epidemic peaked there around November and December, infecting nearly everyone – some with light symptoms and others with severe ones. Krisztina Tasi was in the latter group; she had a stubborn fever. She hasn't heard about many deaths and only a few hospitalizations, and by the time the third wave rolled around, weathering the coronavirus outbreak was almost routine.

Many people in Tiszabő had lost their jobs during the pandemic, but as unemployment was high even before, sadly, that was nothing new.

The village finally having its own GP did help a lot with curbing the virus, and with the help of thorough social work, the town could mitigate the situation well; they distributed vitamins and medicine among the families, Tasi told us. They found that older people are more willing to get vaccinated, the youth do not take the pandemic and its dangers as seriously. Tasi said that it happened that someone changed their mind about the vaccine halfway to the doctor.

Ernő Kadét, a fellow at the Roma Press Centre and the founder of the 1 Hungary Initiative told Telex that there is no data on how Covid-19 affected Roma segregates. They do not know the number of cases or deaths, so it is impossible to compare their situation to that of the entire country. For that reason, he would not say that Romas are "dropping like flies," as others claimed. However, he said that during one week, several people he knew have died of the virus in their 30s and 40s, adding that poorer general health could in itself be a reason for the higher death rates in Roma communities.

Preventive measures are sometimes disregarded

Tibor Béres, an employee of the Autonómia Foundation, works with schoolchildren in a segregate of Gyöngyös, Heves County. Though he has no exact data, in his experience, there were more cases during the first two waves than in the third one, and the second wave took the most victims. A well-known member of the local Roma community has also died of Covid-19, which caused a major uproar at the time.

What spreads faster than the virus in these communities, Béres said, are misconceptions. A lack of knowledge and information contributes to this; people are not aware of what an epidemic entails, how viruses spread. They are also mistrustful of the healthcare system; they do not know how it works, and they are often afraid to visit the doctor.

Because of this, they take the pandemic light-heartedly, playing down its dangers. Many turn down the vaccines, too, fearing it would make them sick. Various forms of misinformation further strengthen these attitudes, for instance, it was widely rumoured that a well-known Roma person died because of the vaccine, but that was, of course, unconfirmed. On top of that, since few households have internet access or a computer, those who want the vaccinate have a hard time registering. Even where there is internet available, it mainly facilitates the spread of fake news and false information. Still, people mostly obey the preventive measures, although Béres added that increased police patrols could be playing a significant role in that.

However, that is not the case everywhere; masks are a rare sight in the streets of Nyírpilis, and people often have to be reminded of the mask mandate in shops as well. "I think this is really sad. It doesn't matter if we agree with the rules or not; we have to follow them," Rudolf Turgyán, a client of the Kiútprogram (A Way Out Program), told us. He hasn't heard of many cases in Nyírpilis and only knows about a single death in a nearby town. He said that even though the vaccine rollout had begun in their village, many do not think it is particularly important and would only get the jab if made mandatory.

NGOs start vaccination campaign

The aggressive spread of fake news and misinformation related to Covid-19 and the vaccines in disadvantaged Roma communities was a returning element in all of our interviews.

Ernő Kadét thinks misinformation is at least as big of a problem as the virus itself. Due to a lack of information, lower education levels, and closed communities, Roma segregates are even more susceptible to fake news and conspiracy theories, leading to higher levels of vaccine refusal.

Like Tibor Béres, he also mentioned the mistrust towards healthcare institutions caused by fear, information deficit, and prejudices against Romas. At the same time, Romas have less access to healthcare: many disadvantaged communities do not even have a general practitioner and roads are in such a bad state that ambulances take much longer to get there.

To improve Romas' attitudes towards vaccination, NGOs are launching a countrywide campaign called "Vaccines for life."

The organizations participating in the initiative are aHang, Dikh TV, RomNet, the Roma Press Centre, the Civil College Foundation, the 1 Hungary Initiative, and the National Roma Council. The campaign aims to get as many people vaccinated as possible. To that end, their volunteers will visit over a hundred segregates, helping locals register themselves for vaccination, hoping to reach around 100,000 people.

This article is a direct translation of the Hungarian original published by Telex on 13 April, 2020.