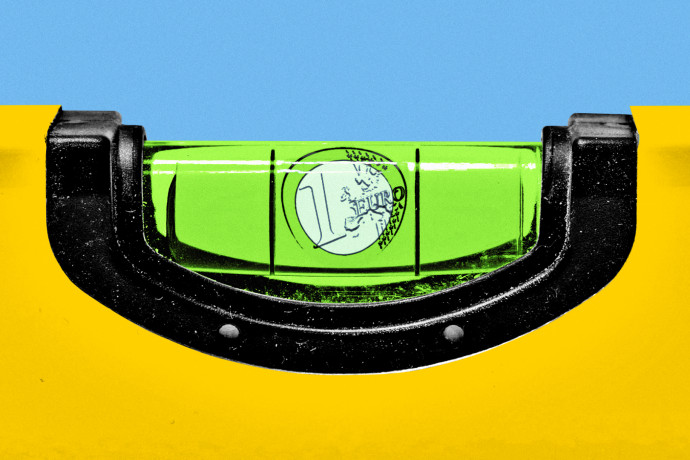

Huge amounts of EU money are at stake, a credit line that can lead to negative interest rates, large-scale government plans, the threat of indebtedness, but also the watchful eyes of the European Union institutions; just what is the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF)? What does it have to do with the mystery of the rule of law, and why does the Hungarian government not ask for ‘free money?’ A quick look at the political dimensions of the EU Reconstruction Fund.

The news exploded like a bomb a few weeks ago, but contrary to previous announcements, the Hungarian government is not yet asking for a 3.3 trillion forint (circa 9.52 billion euros) loan from the EU's Recovery and Resilience Facility and is submitting a new, revised plan for only the non-refundable cohesion funds from the RRF.

The European Commission now has two months to assess the formal recovery and resilience plans it has received from national governments on the basis of the 11 criteria set out in the regulation.

According to the official timetable, the European Commission will process the Hungarian plan by the beginning of July – it will have to evaluate the plans submitted by 26 other Member States a little earlier in the previous two weeks – and the European Council will have the final say.

It is expected that this will result in a non-refundable amount of around 326 billion forints from the new EU support fund around September, which Hungary, like virtually all Member States in the post-coronary economic crisis, may desperately need.

Presumably, the decision on resources has already been confirmed by the Hungarian Parliament in order for the Commission to be able to borrow on the financial markets and to make it as easy as possible for Hungarians to receive the share of the EU fund.

At the same time, this means that the first payments could actually be made as early as mid-2021 with the approval of the Hungarian plan. If all this happens, Hungary will be entitled to receive a 13 per cent pre-financing of the National Recovery and Flexibility Plan: a gigantic amount of EU funding right at the beginning of the election campaign.

But if the hurry is so great, why did the RRF consultation drag on until spring?

RRF funds should be used for pre-defined purposes, such as at least 37 per cent of spending should be spent on investments and reforms in support of climate policy objectives, and 20 per cent on the digital switchover, and there should be continuous EU monitoring of its use until 2026.

That is why many were not surprised that Viktor Orbán finally announced that they were not asking for the RRF loan but preferred the RRF non-refundable cohesion grants.

Recently, the opposition has sharply criticised this decision stating that the RRF framework could inject the Hungarian economy with 3 trillion forints in 2021 and 2022.

In the long run, giving up the RRF loan could leave Hungary owing a considerable amount of interest – potentially in the hundreds of billions of forints – if it borrows from elsewhere, such as countries to the east.

Compared to other conventional international loans, Hungary could borrow from the RRF under much more favourable conditions, with an interest rate of zero per cent (or even negative interest rates) in the long run.

Despite this criticism, the cabinet does not want to increase public debt, so they will not take out a loan, and a nine-component plan has been put in place, taking into account previous promises.

Goals of Hungary and the EU are mismatched

Of course, it may have been clear in the past that many of the investments planned by the Orbán government would not be eligible for RRF funding; the domestic project plans did not meet the objectives of EU programmes, such as the restructuring of higher education institutions. According to many, this is one of the main reasons why the cabinet is trying to get credit from elsewhere, especially if it wants to stick to the ideas it has already agreed to in writing and promised several times domestically.

The RRF plan published in mid-April still included the intention to draw down 3.384 trillion forints (9.8 billion euros) in EU loans although at that time a plan to use the loan was written exclusively for the green, sustainable transport components.

However, out of the total 5.8 trillion forints (17 billion euros) made available to Hungary from the RRF fund, several other goals would have been financed that would not have been approved by Brussels.

To be clear, the RRF money can only be used to support measures that fit into the so-called six-pillar policy areas of European importance. These are:

- green transition;

- digital transformation;

- smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, including a well-functioning internal market, economic cohesion, employment, productivity, competitiveness, research, development and innovation, as well as strong small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs);

- social and territorial cohesion;

- enhancing health, economic, social and institutional resilience, including crisis preparedness and response;

- and policies for the next generation, children and young people, such as education and skills.

All of this was quite difficult to fit in with the original plans, regardless of the fact that the Orbán government was constantly consulting with the European Commission in the background, even during the budget veto, so that an agreement could be reached as soon as possible.

Another aspect may have been the EU's watchful eyes, which, for example, already gave the Budapest metropolitan municipality the opportunity to hold the Hungarian government accountable for failing to comply with its obligation to consult under EU law at the time of the RRF planning.

However, this time money from the EU – the MFF (the EU’s long-term budget for 2021–2027) and the RRF – can only be spent under the ‘shadow’ of the rule of law. This will require a much more serious contribution and source of constant attention: the Orbán cabinet is apparently preparing for the European Commission to monitor the use of EU money much more strictly than before.

The threat to the application of the rule of law mechanism, i.e. control over spending, could therefore have been a real consideration in the government’s tendency to abandon certain ideas.

No matter what came out of it

The draft Hungarian RRF, originally submitted and later withdrawn, calculated an amount of 1.66 trillion forints (4.8 billion euros) for the modernisation of higher education, of which 1.14 trillion would have been from EU support. The largest item, 878 billion forints, was included in the plan entitled ‘Complex Infrastructural, Organisational and Training Development of Higher Education Institutions’, but it simply disappeared from the new version.

After all this, the Minister of Innovation, László Palkovics, promised that the government would add 1.3 trillion forints from other sources to the development of higher education institutions. For the time being, however, it is not clear where this money would come from; although in addition to the model change organised into foundations, university decision-making bodies have just been won with the promise of giga-improvements.

Based on the new draft RRF, approximately 800 billion less would be allocated to green and sustainable transport than previously planned. According to the press close to the government, the budget for the development of fixed-track transport in the Budapest agglomeration accounts for about 77 per cent of the budget, but the opposition said the cabinet did not engage in a wide-ranging dialogue on the previous or current version and ignored the metropolitan municipality's proposals.

Government communications in recent weeks have also stressed that health care will be given a prominent role in the allocation of resources. However, according to the project descriptions, within the framework of all this, it is not mainly infrastructural developments and equipment acquisitions that are expected but the increase in GP salaries promised and announced last year.

The plan would spend 857 billion forints on various health care purposes, of which 300 billion would be medical payroll. This is a long-term employment cost that the RRF Regulation alone would not allow to be financed, but as the government has submitted the relevant ideas to the Commission under the heading of the ‘gratitude withdrawal’ development plan, it is expected to accept a real reform effort, especially in Hungary’s performance with the COVID-19 crisis.

They attack, but in the meantime, they would agree

It is clear that government officials are working to obtain RRF cohesion funds as soon as possible. It could also be questioned that while the EU's priority is to support digitisation and green transition with the RRF fund, the previous 284 billion forints budget for digitisation has simply disappeared from the Hungarian government's new draft, at least compatible objectives are now implied in other chapters.

Nonetheless, Brussels is unlikely to raise any major obstacles, and if the Hungarian plan meets the statutory criteria, at least on paper, they will approve the ideas. Incidentally, the intention of the agreement was also expressed in writing by the Hungarian side in the new draft, as compared to the original plans.

The cabinet has doubled it, so it would already spend 24 billion forints on the implementation of EU country-specific recommendations, which the European Commission expects from all Member States.

Although it is clear from the transformations how many pitfalls the adoption of the original government plan could have been, Szabolcs Ágostházy, the State Secretary to the World Economy for EU Development, recently spoke about the government's decision, jointly examining the borrowing of the RRF loan.

In his words, the loan product offered by the EU does not fit in fully with the objectives of the Hungarian government, moreover, the government also aims to keep the level of public debt stable,

intending to relaunch the economy with the lowest possible public debt.

Of course, this is somewhat contradicted by the fact that the government turned to the international foreign currency bond market back in November and quickly raised 2.5 billion euros from there by issuing bonds and bringing not only receivables but also the public debt to historic highs due to last year's crisis.

Meanwhile, the cabinet says the EU loan is not necessary, but it does not reject future loans from the east, which are more expensive, with higher interest charges and other constraints; let us not forget the recent case of Fudan University in Budapest.

For the time being, only Romania, Poland, Greece, Italy, Slovenia and Portugal have applied for the RRF loans although the other Member States, such as Hungary, still have the opportunity to do so until 2023.

This article and its Hungarian original was created as part of a cooperation between V4 media outlets coordinated by Visegrad Insight, with the participation of the Czech Denik.cz, Slovakian DennikN.sk, Polish Res Publica Nowa and Onet.pl, and Hungarian Telex.hu. The English version of this article was first published on Visegrad Insight.