"There he was, walking with his backpack, and then my kid shouted to him something in English. I later asked him, "Dávidka, what did you say to him?" He says, "Mummy, I told him to run because the police are coming. I mean, he was as young as me", Júlia tells me in the local pub in Csongrád-Csanád County's Domaszék. Although the territory of the village near Szeged doesn't lie directly on the Hungarian-Serbian border, almost all of the local farmers have encountered the backpacking strangers fleeing from the border hunters and the police.

Júlia lives on a farm outside of Zákányszék, next to Domaszék, and says they have found tents and sleeping bags on their property before. "There is an acacia grove on our farm, not far from the house. As soon as the leaves fell, we went out to get firewood, and that's when we found the sleeping bags, it was obvious that they had camped there. My husband said:

“Look at that, I guess we've been having coffee with them every morning.”

Because we usually sit outside, in front of the house for coffee, and from there it's some thirty-fourty metres to the acacia grove."

All locals agreed that the number of those who make it across the border has been on the increase again in recent months. Speaking on Kossuth rádió at the end of August, György Bakondi, the Prime Minister's Chief Adviser on Internal Security, said that "groups of 140-180 people are coming over the fence using ladders in the area of Ásotthalom and Mórahalom and are trying to overrun the defence forces. In addition, people smugglers have also been active, working to move those who have made it through". According to the Chief Adviser, "the police and the border protection forces are in a state of war" and the migrants "regularly attack the technical barriers, police vehicles, as well as the police officers with wooden sticks, stones and metal balls fired from slingshots. He added that seven officers have so far been injured this year".

Abandoned cars all over the place

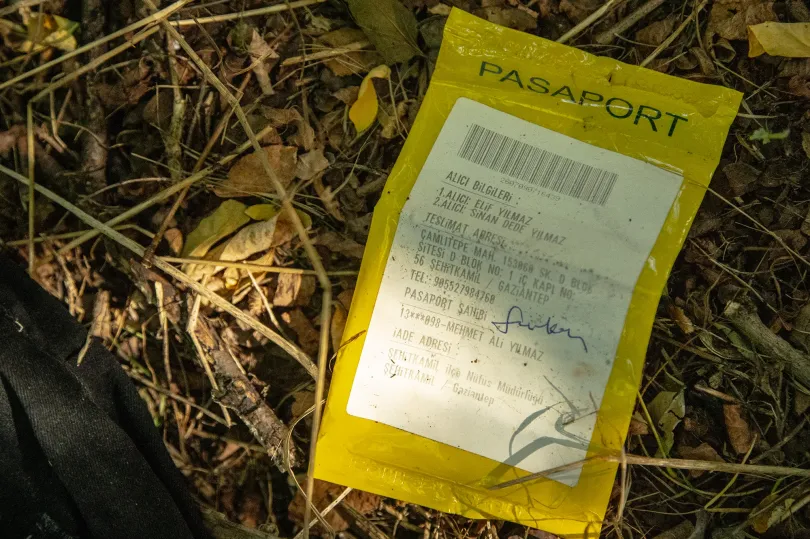

Nobody has seen such aggression further inland from the border, in the areas around Domaszék, Zákányszék, Ruzsa and Öttömös. The most obvious signs of the migratory situation here are cars and minivans left on the side of the road. These vehicles are usually left behind by people smugglers or migrants who have crossed the border and are being chased by the police. They decide to flee on foot, hide in the nearby forest and leave the car behind. Eventually, locals and parts dealers from other parts of the country begin dismantling them.

According to the mayor of Ruzsa, Gizella Sánta, there must be at least 40 to 50 abandoned cars scattered along the roads in her village alone. These cars are usually fresh purchases from some foreign car dealership or were rented from car rental companies abroad. These companies often turn up to claim their property, but by then the tyres have usually been punctured and the more valuable parts removed. There are many such more valuable parts, as the cars left behind include a fair number of vehicles worth between 5 and 10, even 15 million forints: Mercedeses, Škodas, Mazdas, Chryslers and of course a lot of minivans.

"Sometimes it feels like all of Hungary's old Ford Transits and these single-deck minivans are in service around here, making someone a lot of money," the mayor says.

Locals are divided on who exactly is sitting in these cars. Some consistently called the vehicles people smugglers' cars, but many also said that the people smugglers only give their clients the keys and the coordinates of the car still in Serbia, and the migrants then appoint a driver from among themselves. However, not being familiar with the area, they are more likely to abandon the car when pursued by the police.

Most of the wrecks are on roads that belong to the local municipalities, so in principle it should be their job to find the owners. But this is time consuming, as the license plates are usually removed from the vehicles, and the chassis number would be the only way to find the owner – however, the chassis numbers are in registries that are difficult or impossible for ordinary Hungarian municipalities to access.

"By the time you do all the correspondence, report it to the police, find the owner, call the owner to remove the car from the public area – and then they either do it or they don't, usually the latter – it's a pretty long time, during which nothing has happened. By the time this is done, some clever folks have already removed the wheels, taken out the battery, maybe even tipped the car over, and they've removed a whole bunch of other parts." This is why the municipality of Ruzsa is now working on establishing some sort of procedure for this. For example, they will set up a section on the municipality's website where they will upload photos and details of the abandoned cars, hoping that this way, the owners will come forward more quickly.

According to the mayor, there have been cases in the past of people driving around with trailers and simply taking such cars away. While this seemingly solves the situation, it still amounts to theft, as the municipality is obliged to keep the cars for six months.

Noone should be roaming around here

The locals don't judge those who remove parts from the smugglers' cars. A woman from Domaszék tells us that after they found two cars identical to their own, she and her partner asked the border hunters if they could remove the handbrake and the hood, because they needed new ones. And the border hunters said: sure.

"Well, listen, we've got to drain these filthy criminals somehow, since they're here all the time! The locals should at least get something out of this," says a man who introduced himself as G., pointing to a Mercedes stuck in the sand at the border near Mórahalom. The car got stuck under a grove of acacia trees because it couldn't reach the paved road. More and more farmers in the area use their disk tillers on certain sections of the dirt roads. Tractors and combine harvesters can still get through, but the vans and cars used by the traffickers get caught in the deep, soft quicksand. According to the man, the reason the farmers are making the roads impassable is not because they want the cars and want to set traps, but because

"nobody wants them roaming around here, that's the main thing".

According to G., another problem is that those arriving from across the border damage the crop, sometimes they harvest some of it, and even more frequently, they trample it underfoot. Local farmers say that the biggest problem is that clothes are often left in the fields, and when harvesting, a pair of jeans or a sleeping bag can seriously damage a combine harvester. “They leave things everywhere, you pick up the carrots, put them in the wash, and then a Huawei mobile phone falls out.”

The dogs are constantly barking

"Last year, they picked the melons for pickling, but those can't be eaten raw, so they threw them away over there," says József, whose farm is located along one of the dirt roads connecting Ruzsa with Ásotthalom. According to locals, this is one of the busiest smuggling routes, and indeed, there is a white Volkswagen van with Romanian plates parked on the edge of the forest just opposite József's farm. “It was forced down one morning three weeks ago and it's been there ever since.”

At first József says that all he can sense of the migration crisis is that "the dogs are constantly barking", but later it gradually becomes clear that his life has changed, and not only because of the steep decline in property prices in the area since 2015. For example, three of his puli dogs were poisoned, probably by people smugglers, because they barked a lot. He suspects smugglers because he has no neighbours who might have been bothered by the dogs. Since then, the house has been guarded by a young German shepherd, but they also tried to catch him – József once found a belt by the fence and the dog was dragging his leg.

He and his wife were fortunately unharmed, but one time an immigrant jumped into their garden at night, with police cars with sirens on his tail. “My wife was the only one home, she called me at 2am to tell me what had happened, but I think I would have also been scared in that situation.”

Many of the farmers in the area have installed cameras, and an acquaintance of József's was worried about his beautiful horses, so he bought two huge dogs. "That's one place they won't be going to anymore," he says.

There are foreigners coming and going

According to Gizella Sánta, there have been no cases of refugees hurting anyone in Ruzsa. Despite this, locals, especially those living alone on the outskirts and farms, sometimes complain about not feeling safe. “My mother is 85 years old, she lives in the street at the end of the village. Her back garden overlooks the farmland, and she says the dog is barking all the time and she doesn't feel comfortable. It's impossible not to think about it, we know that there are foreigners coming and going there, and they're not tourists. And okay, they aren't coming in, and we hope it stays that way. But hoping is not the same as everything being OK.”

At the same time, the mayor says that the locals, who see those fleeing from the police every day, do feel sorry for them. "Obviously, it's easy to judge and huff and puff until you meet them in person. But here we do see them. Once, on a Saturday morning, while I was doing my shopping at the market, a smuggler's car rammed into one of the houses. Those poor people scattered within three minutes. Obviously, they were later picked up by the patrolmen, but one doesn't forget the barefoot man in a long-sleeved shirt and jeans, holding his scarred belly not completely covered by the shirt. I could see that he was suffering.

Obviously, in such cases, one sees that this is a wounded man standing in a village at the end of the world – it's the middle of our world, of course, but the end of the world for him, – not knowing which way he is facing, or whether he will even be treated, what will be given to him, and what won't. Such encounters are still very moving. At the same time, it is our simple little lives that are being disturbed. So it is a very ambivalent thing, you know.

I do feel sorry for them, I really do, but who will feel sorry for the people who live here?"

According to the mayor, the situation in Ruzsa has started to improve since they hired two patrolmen. It seems that since then, many of the smugglers started moving through the surrounding villages instead. Truth be told, the situation of the patrolmen is not easy either: they can intercept the migrant groups, but all they can do is call the police and wait. “Obviously, it's happened on a few occasions that they‘ve had to guard a group for half a day. I don't think, of course, that it was on purpose that the policemen took so long to come. Rather, they were likely called to two other groups and just couldn’t get there soon enough.”

Parallel worlds

Everyone agrees that the biggest threat to both locals and migrants was the increasing number of car chases. In almost every village, we were shown houses that had been hit by cars, and in many cases it was really down to luck that no one was hurt in these accidents. The mayor of Ruzsa says that a few days ago a car coming from Szeged was zipping through the village's central crossroads, when it tore up the road signs and " completely covered the Father's car with soil". In the pub in Zákányszék we were told that one of the roadside crosses had recently had to be renovated because it had been knocked over by a foreign car. Other than this, there is little physical contact between the worlds of the refugees and that of the locals. As Gizella Sánta puts it:

“It's so interesting by the way, knowing that there is another world existing parallel with ours. These things do happen here, but they aren't happening to us. Although this world is also here, in a way, yet it’s completely different, and we don't know when it's going to pop and spill onto us.”