No major act of election fraud, just a bunch of dirty little tricks

Even the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) declared Hungary's last parliamentary elections in 2018 to have been free from foul play (in a legal sense). However, the team of election observers found that the playing field was so tilted in Fidesz's favor that the election was far from a fair competition.

Problems highlighted in the 2018 OSCE report included: the state of the media not enabling voters to be properly informed, the ruling parties' ability to make use of public funds for campaign purposes, discrimination against citizens who were voting from abroad, fake political parties running simply for the subsidies, and a lack of transparency in campaign financing.

But how will the 2022 election compare?

The organization is monitoring the situation in Hungary again this year. In fact, it has deployed a full election-observation mission to Hungary, which is newsworthy given that Bulgaria used to be the only EU country considered to warrant such measures. 18 of the mission's long-term observers have already been in Hungary for weeks, and a further 200 observers are due to arrive for this weekend's elections.

They have already published a preliminary report, which, among other things, described a systemic political bias in the public media and pointed out that, "Election campaigning by public officials is not restricted in any manner by the law, and the use of administrative resources in the election campaign is not prohibited."

We've gathered together the critical points that are most often raised regarding the fairness of elections in Hungary, and here we'll explain what you should know about them.

Distribution of parliamentary seats

With its first two-thirds majority in 2011, Fidesz tailored the electoral law in its own image. There are plenty of things that could be singled out from these changes. They range from the electoral system having gone from two rounds to one round to the fact that the proportion of party-list seats has decreased compared to the number of single-mandate constituencies. But first, let's just focus on the following:

- The "winner compensation" mechanism was introduced, which earned Fidesz an extra 6 seats in 2014 and 5 seats in 2018, but this time it could even benefit the united opposition;

- The electoral districts were redrawn so that if the governing parties and the opposition had received exactly the same number of votes in 2018, the governing parties would have won 57 percent of them and the opposition only 43.

The issue of minority mandates should also be mentioned here. Only national minority self-governments may prepare a national list, and those who vote as a national minority cannot vote elsewhere but that one list, so in effect, minorities don't have a real choice (except when voting for individual candidates). Further, minority lists are subject to the influence of the side with more resources.

Currently, there is only one minority MP in the National Assembly, Imre Ritter of the German minority. He used to be a Fidesz politician and has consistently voted in line with the governing parties. Nevertheless, despite having asked the administration for help on an issue of importance to the German community, he hasn't received any support. Ritter is expected to be re-elected this year, but as the general assembly of the ORÖ (The National Roma Self-Government) was mired in scandal after the Fidesz candidate had not been voted in as list leader, no other minority will be putting forward a list.

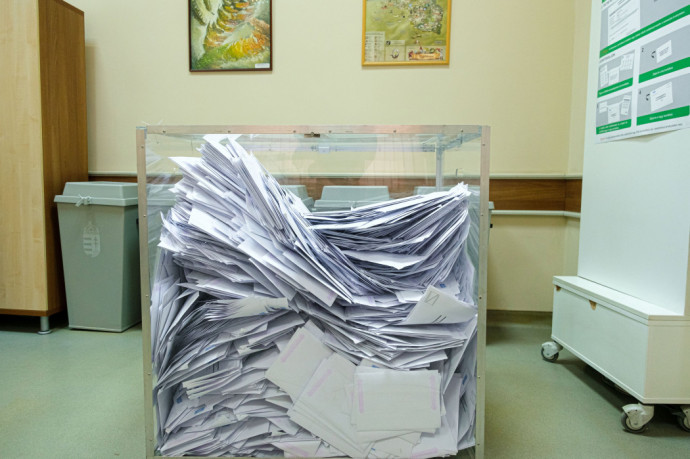

Mail-in ballots

With regard to citizens living or residing abroad, Hungarian electoral law distinguishes between two types of citizens with the right to vote: those who have a registered address in Hungary and those who do not. Participation is considerably more complicated for the former – they can only vote in person at a consulate, whereas the latter can cast their vote by post, but only for party lists, not for individual constituency candidates.

The turnout rate among Hungarians in the West is roughly one-sixth that of Hungarians living outside of Hungary who are eligible to vote by post.

According to the Constitutional Court, there are "reasonable grounds" for this discrimination, but it is also clear that the Fidesz-KDNP alliance, which currently enjoys a two-thirds majority in the government, would not be interested in creating an institution for postal voting for everyone. 95% of voters who cast their votes by mail in 2014 cast them for Fidesz, and 96% of them did the same in 2018. However, among Hungarians living in the West who have an address in Hungary, voters that are critical of the government are over-represented.

According to a February poll, only 11% of those living abroad would vote for Fidesz-KDNP this year, while 43% would vote for the joint opposition list.

Moreover, mail-in voting in its current form raises technical concerns. According to a Transtelex article, there are loads of loopholes. The system is not even capable of detecting if someone's ballot envelope had been subsequently opened and the ballot tampered with after having been sent out, or if votes were cast on behalf of deceased individuals. Moreover:

- In Serbia, it wasn't even the post office who delivered the ballot papers this year; rather, they were distributed and collected by activists of the local Fidesz affiliate;

- In Romania, the Hungarian People's Party of Transylvania (EMNP) advertized that it is not a good idea to rely on the post office to return the ballots, and it urged Transylvanians to entrust this task to EMNP representatives instead;

- The deputy mayor of Suplacu de Barcău (a member of the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania) went from door to door in his municipality to collect the mail-in ballots;

- And near Târgu Mureș towards the end of March, a journalist discovered discarded ballot papers that were already filled in.

Fictitious addresses and voter tourism

In recent years, dozens of fictitious addresses have been established in Hungary by people who also wanted to vote for a constituency candidate or possibly to influence the election of a mayor in parliamentary elections without actually living there. This had been illegal for a long time, but after more than a decade of NGOs regularly drawing attention to this kind of election result manipulation, a government majority adopted an amendment that changed the definition of residence last November.

According to human rights organizations, in practice, this in fact legalized "fictitious addresses" and gave the green light to organized voter tourism. András Milánkovich, a lecturer at the Department of Constitutional Law at the ELTE Faculty of Law, has an interpretation that is a bit more nuanced: the establishment of a fictitious address is no longer punishable as forgery of an official document, which means that it will not be a crime against electoral law if 50 people register at a single apartment – however, carousel voting will still be prohibited.

Fake political parties

With the replacement of the endorsement slip system with recommendation forms (which also has its issues), the door has been opened to so-called fake parties and business parties. These are entities that are not engaged in real political activity. They obtain at least some of the signatures they need to run for office illegally (e.g. by copying data from other parties' recommendation forms), and they try to put together a national list in order to receive hundreds of millions of forints in funding.

In 2018, 100 parties were registered for the parliamentary elections, more than half of which still owe the state their unearned campaign contributions.

The anti-vax, bodybuilding celebrity pharmacist György Gődény's party, Közös Formáció [lit. "Common Formation"] is one that has not repaid the 153 million HUF (roughly 415,000 euro) state subsidy for putting together a national list. However, this did not deter Gődény from putting up a new anti-vax party in this year's elections.

In addition to the Gődény-branded Normal Life Party, the Solution Movement of pornsite businessman György Gattyán (whose net worth approaches one billion euros) is also standing in the elections this time. Both parties have submitted suspicious recommendation forms this year, even prompting a police investigation.

The fake party phenomenon is designed to throw a wrench in the system. According to analysts, this works in Fidesz's favor, as it could mislead some voters who are less politically engaged and dissatisfied with the current government. Rather than supporting more promising opposition parties, said voters may waste their ballots on fake parties.

Non-stop campaign mode

Apart from the fifty-day campaign period leading up to the elections, there are no rules on campaigning, and the ruling parties can use public resources to promote their own political messages. As a result, Fidesz-KDNP has much more visibility to voters in between elections than opposition parties.

This includes the institution of the NER national consultation, government poster campaigns, and the so-called child protection referendum on election day this weekend, which keeps the anti-gay sentiment on the agenda (a campaign theme for Fidesz).

The disparity in funds between the governing parties and the opposition is also reflected in the fact that the government side spent eight times more on poster campaigns than the opposition. It is also important to note here that the publicly funded Civil Union Forum (CÖF) spent around 633 million HUF (~1.7 million euros) on Fidesz posters, which makes it clear why it is problematic that, with Hungary's current system, NGOs are not even subject to as much regulation as political parties. This in turn is a breeding ground for the practice of outsourcing campaigns to a grey area, as can be seen in the case of political advertising on Facebook.

Media dominance

In addition to direct campaigning, the extent to which voters have access to unconstrained, non-partisan information also plays an important role in judging the freedom of elections. Although the public media, which operates on 130 billion forints (~350 million euros) a year, is supposed to be non-partisan, instead:

- over the last four years, it has almost exclusively invited pro-government politicians on its shows, and during the campaign period it allotted all of five minutes to each opposition representative;

- leaked audio recordings prove that Orban's associates dictate the news to the state news agency, which suppresses stories that embarrasses the government;

- managing editors of the public media explain to their staff that they are to support the government during the campaign, and anyone who doesn't like it should hand in their resignation.

In terms of freedom of the press, Hungary was not excelling 4 years ago – during its last elections – and the situation has only worsened since then: according to Reporters Without Borders' World Press Freedom Index, Hungary has dropped 19 places and now ranks second to last among EU countries. We wrote a detailed article in our news section "Complex" about how Hungary's free media has been dismantled by authorities over the past few years.

Translation by Dominic Spadacene.

To stay informed about news from Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!