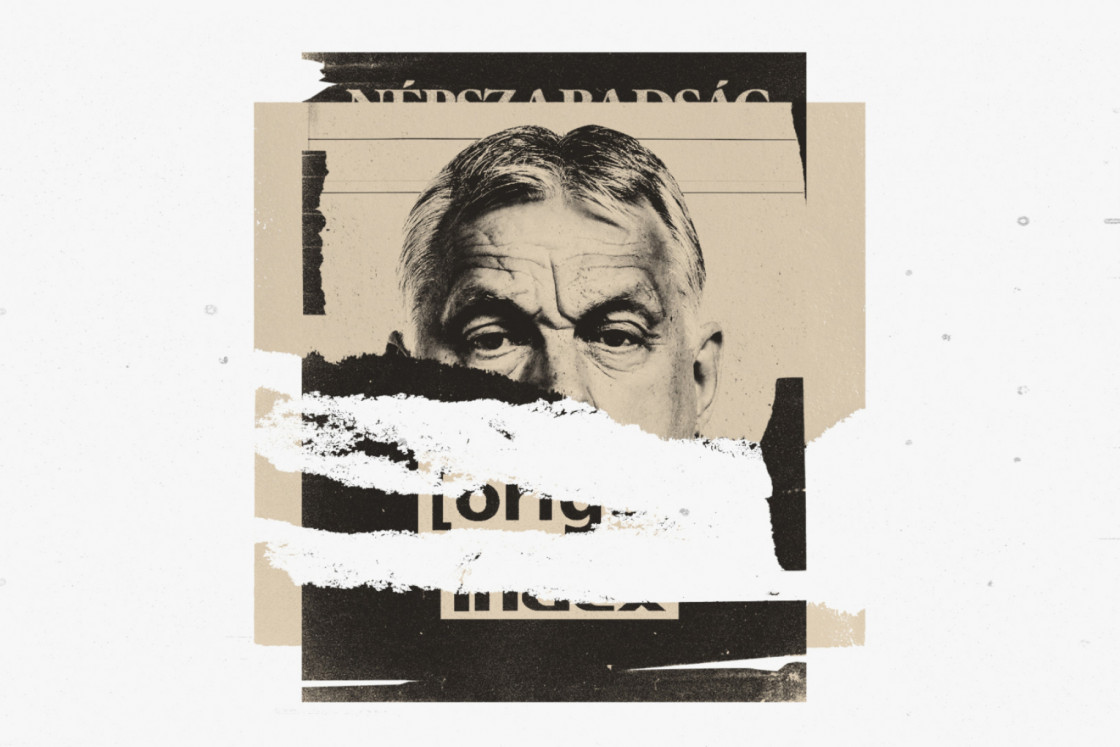

The shredding of the free press in Hungary

For 30 years Viktor Orbán and his old political colleagues have held the view that the press is against them, that journalists always help their opponents. If Fidesz loses, they think, the power of the press has won. If Fidesz wins, it does so in spite of the media headwind. The same line was taken in Orbán’s 2019 governmental press conference— when he told members of the Hungarian and foreign press that more journalists were against him than for him, “but even in such circumstances it is possible to win” — as in the analysis of the 1994 election result, where Fidesz’s defeat was blamed on a media superiority stacked up against the party. However, the party did not always view the press this way. Translation by Charles Hebbert.

In this article we look at the development of the Hungarian media over those 30 years. Today, Hungary is in a dismal 92nd position in the World Press Freedom Index, which is put together by Reporters without Borders (RSF). How did it reach the point where ownership of most of the Hungarian TV, radio, printed and internet media is in some way tied to the government and its politicians.

Orbán burst into the public awareness in 1989 with his speech at the reburial of the 1956 leader Imre Nagy. In the early 1990s he was popular among journalists. “Viktor Orbán only had to lift his little finger and the press fainted,” one political commentator said. In its early years Fidesz’s star rose because its politicians were younger, cooler and more dynamic than those of the other parties. When they entered Parliament, they realised this gave them a public platform for their brand of politics. Within a couple of years Fidesz was by far the most popular party in the opinion polls, frequently scoring more than 40 percent. It looked like it might be able form a government on its own after the next election.

However, this sudden popularity proved volatile. Fidesz only just made It into Parliament in the 1994 elections. With only two MPs, it was the smallest party in the chamber. There were several reasons for this decline. The party kept its distance from the Democratic Charter — a popular movement in 1991-92 among the opinion-forming intelligentsia against the gathering strength of rightwing elements around the government — because it did not want to share a platform with the former Communists.

Then Fidesz’s clean image was sullied when news leaked of a secret property deal its leaders had signed with the ruling party that brought a whiff of corruption. And finally, the party started moving to the right, and increasing internal strife between Orbán and Gábor Fodor led to Fodor leaving the party, which the press deemed a mistake.

These were all separate issues, but the party leaders felt there was a common thread: that the media was against them. Their election post-mortem blamed the “concentrated campaign” in the press against the party for its poor performance: “We did not solve the problem of how to get the real content of our political message across to voters in a media environment that was almost exclusively hostile to Fidesz.”

Fidesz’s leaders felt it was unfair that the other parties had economic and cultural resources which gave them a strong presence in the media, while Fidesz had access only to billboard adverts through the Mahir advertising company that had come under its sphere of influence. (They viewed the acquisition of state assets by members of the Hungarian Socialist Party — the MSZP, which had been formed out of the old Communist party — as particularly dishonest.) Orbán and Co.’s antipathy was fuelled by the disparaging attitude of the media elite. The party’s leaders were gauchely defiant boys from the provinces and the metropolitan intellectuals made it clear that these lads should be happy to play football on the grown-ups’ pitch. Orbán complained in one 1993 interview that journalists had overstepped the mark when they started telling him what he should do in his debate with Fodor.

“We’re going to throw you back where you belong, in the rubbish heap where we pulled you up from,” a well-known journalist apparently said to a Fidesz leader at this time, which became enshrined by Fidesz as the media’s view of the party.

You need money and your own media to achieve a stable political presence

The Fidesz elite concluded that they needed money and their own media to become a regular political player. This was the point made by Lajos Simicska, an old friend of Orbán’s and an expanding businessman, when he said to the newspaper Népszabadság: “In politics, like in war, you only need three things.”

The first attempt to acquire a footing in the media came in early summer 1994, between the two rounds of the general election, when Mahir leased the publishing rights for three newspapers from the state publishing company Hírlapkiadó. This was an attempt to keep the newspapers out of the hands of the MSZP, which was expected to win the elections. However, the new Socialist government of Gyula Horn quickly took back control of the papers and dismissed Gábor Liszkay, the head of Hírlapkiadó (he later became a key figure in Fidesz’s media world).

Between 1994 and 1998, Fidesz had enough financial clout to start the daily paper Napi Magyarország, but it was only after Fidesz won the 1998 elections that the big moves came.

Once in power, Orbán announced that he would create a level playing field politically in the media. Fidesz set about replacing leading figures in public service broadcasting who were considered left-wing (although the “Fideszising” of the media fell a long way short of what we see today). It also seized control of the huge media portfolio of the newly nationalised Postabank and shut down Kurir, a newspaper that had given publicity to some awkward issues for the party.

The other key moment in the first Orbán government’s handling of the media came when Fidesz merged Napi Magyarország with the established daily Magyar Nemzet, which handed it a readership of 60-70,000. This “brutal newspaper occupation” drew protests from figures such as Ferenc Madl, a former minister whom Fidesz later nominated to be the country’s president, and Péter Boross, the former conservative Prime Minister. The government’s defence was the same argument it uses today: a strong and effective rightwing press was needed to offset the left wing’s dominance in this field.

Fidesz also offered an escape route for the more moderate journalists who had been forced out or had resigned from Magyar Nemzet (only 20-25 of the 70-strong work force was left at the Fidesz-controlled paper) by setting up a weekly magazine, Heti Válasz, under István Elek, an adviser to the Prime Minister. This was presented as a moderate conservative publication, and for this purpose to government set aside 1.5 billion forints in the 2000 budget, according to the magazine Magyar Narancs. When it came to pumping up its own media, the first Orbán government wasn’t mean-fisted either. In the first half of 2002 the top 10 advertisers were all state companies, and in the six months up to the elections in April 2002 the state-owned gambling service Szerencsejáték spent 211 million forints on advertising in Magyar Nemzet and the Prime Minister’s Office spent 133 million forints.

However, even the influence gained through having the control of a strong daily and weekly papers and the public service media couldn’t help Fidesz win the 2002 elections.

This was how the defeated prime minister explained his defeat:

“Our mistake was not that we were confrontational, but that we did not defend our decision cleverly enough. We should have showed more effectively to the public that the aims which we were confrontational about were good aims. The government’s communication was not clear enough. We should have spent more time and money on this in places that were not part of the dominant liberal media. We should have created more space in the printed press, the electronic media and so forth. We should have opened up more channels of communication, which is not just a media question. It was good to set up Heti Válasz, but we should have started more newspapers. We missed that chance.”

This disadvantage was well expressed in a quote attributed to the Fidesz leader László Kövér: “We were in government but not in power,” i.e., the strength of the left-wing liberal mainstream in the economy and the media prevented the Fidesz government from realising its plans. The Fidesz leadership had once again reached the conclusion, as in 1994, that it needed more media outlets of its own to realise its own politics. The next eight years in opposition confirmed this view.

If the right wing wants a television channel, it should buy its own Orbán focused on the media right from the start in opposition. He addressed a demonstration by the Alliance for the Nation group in front of the Hungarian Television building in August 2002, calling for a new Media Law that divided the public service broadcaster into two equal parts, one for the left and one for the right wing. He said if this did not happen, he would organise a referendum on the matter. To which Prime Minister Péter Medgyessy replied that if the right wing wanted a television channel, it should buy its own. Fidesz took his advice. The former government spokesman Gábor Borókai and 20 others set up Hír TV at the end of 2002, which fell into Simicska’s hands within 18 months.

For Orbán, for Fidesz to have its own media was important, not merely to get its message across to its supporters, but also to defend its members and — crucially — to launch political attacks.

On 17 June 2002, Orbán visited the offices of Magyar Nemzet, to meet the editor, Gábor Liszkay. The next day, Magyar Nemzet broke the story that Medgyessy had been an informer for the Ministry of the Interior, code number 209, in the last years of Communism— according to the account by Dániel Rényi Pál in his book Triumphal Coercion.

Magyar Nemzet was to operate as an attack dog for Fidesz: in less than one year 95 libel actions were launched against the paper, three times more than were filed against the three left-wing papers. It lost most of the cases and paid out millions in fines.

Fidesz and its press was to use the same trick in the run-up to the 2018 elections. The government-backed media published a stream of allegations about its rivals, for example that opposition leader Gábor Vona was gay and was a member of a Turkish terrorist group. Fidesz constructed whole campaigns on these claims. After the election was won, the media published a string of apologies, but it was worth it. At the cost of a few million forints in fines and the shredding of the media outlets’ integrity the party won another two-thirds majority in Parliament, which gave it continued access to unbridled power.

The party’s media played a vital role in another important event, when Orbán wanted to tune his supporters into the imminent leaking of the infamous Őszöd speech by Ferenc Gyurcsány, the Prime Minister. (Gyurcsány was speaking to a closed meeting of the Socialist parliament party after the election, calling for radical reforms. He said the public had been misled for too long by politicians; Orbán successfully presented the speech as meaning the Socialists had been lying to get re-elected.)

Orbán had advertised his campaign of falsehoods in a speech at Tusnádfürdő in the summer of 2006. The campaign took the form of a series of articles and full-page adverts in Magyar Nemzet before the leaking of the speech on 17 September. When an angry mob besieged the Hungarian TV building in Budapest the next day — one of the defining moments of post-1989 Hungarian politics — the Fidesz-friendly Hír TV was the only channel to broadcast the siege live. A million people watched the events, footage of which was used by the world’s press, including CNN and the BBC.

The publication of the Őszöd speech was a turning point for Orbán. After his second successive election defeat in April 2006, he was fighting for his political life as clamour grew on the right wing for a change in leadership. Now Simicska’s Magyar Nemzet gave Orbán a lifeline. In January 2007 an anonymous article in Magyar Nemzet accused moderate Fidesz politicians of planning to set up a new party, and told the “plotters” that Orbán’s position as leader of the right wing was unassailable. Certainly Orbán’s tight grip on the right-wing media through his old friend was going to make any challenge to his position almost impossible.

Another important chapter in the party’s empire building came in 2009, when the Fidesz, Christian Democrat and Socialist members of the ORTT, the supervisory body for television and radio, agreed to divide the frequencies of the two main national commercial radio stations between left and right wing.

By the end of eight years in opposition, the party had on its side a campaigning national daily, a weekly magazine, a free weekly paper with a print-run of 1 million (in a country of 10 million people), its own news TV channel and commercial radio, to name only the key components. Orbán’s circle had done their homework well.

Once he had won a two-thirds majority in Parliament in the 2010 elections, Orbán moved up a gear.

Changed media consumption

Hungary’s standing in the World Press Freedom Index has changed markedly over the past 15 years. In 2006 it was in 10th position; by 2010 it was down to 23rd, and today it is 92nd, below all the other EU countries save Bulgaria. His thumping parliamentary majority gave Orbán far greater room to shape the media to suit his own political aims. The 2010 Media Law was first major step in the restriction of press freedom, and we can trace the successive steps of this process right up to the closure of Klubrádió this year.

- The shaping of the public service media has reached the point where editors in this 118 billion forint (£272 million) machine tell their staff: the government must be supported in the election campaigns — and anyone who does not like that can resign. An important feature that is often overlooked is the state monopoly of news. For the Hungarian News Agency (MTI) is a part of the state media and since 2012 has been offering its services free. As a former head of MTI, Mátyás Vincze, pointed out, taxpayers’ money is being spent on putting out free “pro-government” news, making it impossible for independent news agencies to survive on the market.

- The public service media has played a determining role in the subjugation of television and radio, since MTVA, the state media conglomerate, has seven TV channels and five radio stations. The state distribution of radio frequencies has meant that almost all stations are in government-friendly hands. Next, it was the turn of the commercial TV stations. The TV2 channel belonged to the German company ProSiebenSat1 until 2013. It turns out that Lajos Simicska, who by then had fallen out with Orbán, had a chance to buy the channel but it was snapped up by Andy Vajna, the pro-Fidesz film producer, and is now in the government stable.

- In autumn 2018 the government set up the Central European Press and Media Foundation (KESMA): this strategic body has a portfolio that includes Hír TV, the Origo website and the newspapers Magyar Nemzet, Blikk and Bors, as well as all the regional dailies. The state has not had such a stake in the media since pre-1989 state socialism in Hungary. Such a concentration of media, with a total of more than 500 media outlets in one centrally controlled foundation, is unparalleled in Europe. KESMA was set up by members of Orbán’s inner circle and, while in private hands, is mainly supported by public money.

Furthermore, both the online and the printed press market have been reshaped, as the examples of the websites Origo and Index and the national daily paper Népszabadság show. The placing of the government yoke on Origo in 2014 and the burial of Népszabadság in 2016 were two symbolic milestones in the “Nerification” of the media — the terms takes its name from the System of National Cooperation, or NER, the political regime introduced by Fidesz in 2010. The former had been a pioneer in the online market and had a big readership, while the latter was the national daily with the largest circulation, even if its print-run had fallen to a mere 37,000 by the time it was closed. Looking at the fate of these two outlets, a certain pattern appears.

“I think it was high time that Népszabadság closed down unexpectedly, in my humble opinion”

This interesting statement was by MEP Szilárd Németh, vice-president of Fidesz, when he heard that the paper was closing. It was indeed unexpected when couriers arrived at the homes of the newspaper’s journalists to tell them Népszabadság was not moving but was closing down. In the previous months there had been much talk about how the government wanted to bring the paper’s publisher into its sphere of influence. It was thought that maybe the government had its eye on the portfolio that included 13 regional papers, rather than Népszabadság itself. It didn’t offer much hope that the newspaper had already become a business-political toy when it was sold off by the publisher Ringier to Heinrich Pecina in 2013.

In the case of Origo, it subsequently became clear even before the departure of the website’s editor-in-chief in 2014 that dark clouds were gathering. In an analysis by the website 444.hu the game was up for the news website in 2013. When Magyar Telekom, Origo’s publisher, was in tough negotiations with the government about mobile phone networks, Kerstin Günther, the new German boss at Magyar Telekom, arrived with the task of smoothing out any conflict with Orbán. In the end the company paid 35 billion forints for extend its operation until 2022, and it also sacrificed Origo.

Both Origo and Népszabadság had been giving publicity to stories that were causing difficulties for Fidesz.

Origo had been writing embarrassing stories about expensive foreign trips made by János Lázár, who was at the time a junior minister. Lázár insisted that the costs were all above board, but after Origo’s revelations he paid the money back rather than reveal who he had been holding secret meetings with abroad.

The front page of the last issue of Népszabadság had two such stories: one concerned the divorce of György Matolcsy, the head of the Central Bank, and his relationship with a staff member, and the other was about the helicopter rides that Antal Rogán, Fidesz’s propaganda minister, had made to go to a wedding — which he denied until photographic evidence was produced. (Revealingly the press conference that Rogán gave on that story more than four years ago is the last time that he has appeared in front of the press. The man who used to be constantly in the tabloid press has almost been in hiding.)

Orbán and the other Fidesz leaders repeatedly pin the blame for their own political failures on the “liberal left-wing dominance” of the media. Curiously, the axe fell on Népszabadság just six days after the government’s embarrassing failure to win a much-heralded referendum against the EU and its migrant policy on 2 October 2016.

Naturally, the official line never mentioned silencing voices critical of the government or evening up the balance of media power. In both the cases outlined above, and later in the case of Index too, the publishers presented their actions as economic rationalisation or restructuring. In 2014 Miklós Vaszily, the CEO at Origo at the time, firmly denied that there had been any political pressure to dismiss Gergő Sáling. He referred to realising integrated content-production strategy and to changing patterns of “media consumption” — a phrase that is regularly trotted out. When Népszabadság was closed down, it was initially said to be making a loss and negatively affecting the overall company results of Mediaworks. Therefore publication was to be suspended until a new approach had been worked out — but it has never appeared again.

At Origo there was a gradual replacement of staff, and at the end of 2015 Magyar Telekom sold the news site to New Wave Media, a beneficiary of hundreds of millions of forints from the Matolcsy-style Central Bank foundations, before it ended up in the KESMA.

In neither company did the journalists accept the story that was fed them. The Origo staff said publicly that they did not agree with the dismissal of Sáling and that they did not feel that their continued work was secure. The wave of resignations that followed was no surprise. The staff at Népszabadság had no choice. On the newspaper’s official Facebook page they wrote: “Dear followers, the editorial team heard at the same time as the wider public the news that the paper is being closed down immediately. Our first thought is that this is a putsch. We will report back soon.”

In spite of claims that simple market forces were at work, the paralysing of the two news outlets aroused a strong response, with protests on the streets. The government’s embarrassing affairs did not completely go away. Many people wanted to hold Lázár to account for both his travel expenses and the changes at Origo.

In this article we have concentrated on the “Nerification” of the media There are other issues that define press freedom and freedom of information that have not been the focus of this article, but are nonetheless important:

- How a government finances its own media through state adverts. (The distorting effect on the market of state spending did not begin in 2010, but on the basis of revenue about 80 percent of the media is financed by Fidesz-related actors in 2019, according to the estimates of media watchdog Mertek Media Monitor (Mérték Médiaelemző Műhely);

- How the independent media are given restricted access to government figures, state officials and public information;

- How the right of freedom of information is rendered hollow when the already very lax timescales for responses to requests for information can be extended without any justification;

- How the independent press is branded as part of the opposition;

- How troll media such as Pesti Srácok and Pest TV are used to terrorise the opposition and the independent media; connected to this is the training of a right-wing internet army and the question of the spending of public money on social media adverts.

It took ten years for the government to capture Index

One of the most important — and most drawn-out — chapters in Fidesz’s conquest of the media was the annexation of the Index news portal. Since all the staff at Telex, including the authors of this article, used to work at Index, we watched the events from the inside and can give a detailed account of what happened.

Index was one of the first Hungarian news websites and went from a garage operation to being a dominant force in the Hungarian media market by the early 2000s. The appearance of internet media wrought changes in both media consumption and advertising and raised questions about how viable an internet newspaper was as a going concern.

The news portal was set up by a group of individuals who invested in the operation and development of the website. However, the bursting of the dot.com bubble worldwide made it difficult for internet companies. The first stage in the news site’s loss of economic independence came in 2002, when Wallis, an investment company, bought a 31 percent stake in Index. A series of steps led to the CEMP media group taking 100 percent control of the website. It soon emerged that the real head of CEMP was Zoltán Spéder, a banker who was close to Fidesz. Spéder had had good relations from the 1990s onwards with both Fidesz leaders and left-wing figures such as the economist András Simor and the Socialist politician Gordon Bajnai.

Spéder and the editorial team had their conflicts from the start. Prior to 2010, these mainly revolved around the entrepreneur wanting run the publisher as a traditional company, while Index was structured in a more relaxed and less professional way which had a beneficial effect in terms of the newspaper’s content and the writers’ development. In the run-up to the 2010 elections, however, the atmosphere around Index became more tense as it became clear that Orbán was not only going to win, but also stood a good chance of getting the two-thirds majority that would allow him to rewrite the constitution,. In 2009 Spéder was told would not be able to keep Index because of his economic exposure, according to Index’s editor-in-chief, Péter Uj.

Indeed, once Orbán was back in power Spéder got word from Fidesz circles that things needed to change. The tension ran through the whole company, with rumours going round that Spéder was about to sell up to NER investors. In 2011 several senior colleagues left, and Uj resigned. Events strengthened the belief that the government was exerting control over the portal in some form, but the editorial team retained its autonomy in spite of more attempts to apply pressure.

In February 2014 Orbán’s old ally Simicska acquired — it was not clear how — first refusal on Index. (There were rumours at the time, but the editorial staff and the public only learnt that this had happened later, in 2017.) His relations with Orbán were cooler by then, so it was ambiguous whether he acquired rights to Index to help Fidesz or quite the opposite. After the elections later on 2014 war broke out between the two old friends and all the publications that Simicska possessed turned on the government. At the same time, Orbán commanded his circles to annexing the Hungarian press at an unprecedented rate. A bitter campaign was launched by the government against Spéder, who had considerable economic clout and media influence. As a result, Spéder sold his bank, with its public utility interests, and his property portfolio to government supporters; his media empire, however, did not fall into Fidesz’s hands.

Government figures were keen to know who owned Index. Even though Orbán dismissed criticism of Fidesz’s growing media control by claiming that the government had no interest in privately owned media, his own minister Antal Rogán took a different line in response to a question from Index at a local forum. He said:

“I think Lajos Simicska is the owner of Index”.

The government reckoned that by playing the Simicska card, the editorial team would implode: there was no need for direct government intervention to weaken Index. However, Simicska didn’t keep Index. Through another opaque deal he sold it to a foundation, while the editorial team carried on its work. This move infuriated the government, which openly expressed its disappointment. Fidesz’s youth groups organised protests against Index, and almost every day leading Fidesz politicians stated that they did not respond to the Simicska media.

After its election victory in 2018 — a third successive two-thirds majority — Fidesz moved up a gear in its shredding of Index. Simicska laid down his weapons and handed over everything to Orbán’s men. Spéder sold off the company that handled Index’s advertising — half of it was bought by József Oltyán, a provincial businessman who belonged to the KDNP, the Christian Democrat party that is Fidesz’s junior partner in government. While Index still belonged to the foundation, financially it was at the mercy of a politician-entrepreneur who was close to the government. While there were various theories about why Oltyán had got involved, the real question now was this: since the government’s people had got hold of the company that published Index, when would they begin to interfere editorially?

Index’s fate must have been sealed at the time of the 2019 local elections, according to informed sources. The campaign was dominated by embarrassing scandals that dented Fidesz’s clean image and played a role in the party’s poor performance. One view was that Index’s coverage of these scandals was the final straw. Another government source said that the opposition’s gains and the victory of Gergely Karácsony in Budapest convinced senior party figures that the Index problem needed to be “solved” before the next election.

Miklós Vaszily, who had become the NER’s media supremo, thereupon acquired half of the publisher responsible for Index. At this point, events speeded up. Citing financial issues resulting from the pandemic, the publisher began negotiations on how to cut back or restructure the editorial staff. One of the aims may have been to interfere in the content of the website, whether by controlling resources or by breaking up the structure of the team. When word of these secret talks reached the staff, they moved their “independence barometer” to the danger zone. In response, the editor-in-chief, Szabolcs Dull, was dismissed for confidential reasons. The staff asked for his reinstatement, and when this was not forthcoming, they resigned en masse. Most of the team stayed together and set up Telex in autumn 2020.

Telex has a small amount of advertising income but relies heavily on reader contributions. If you believe that a free and fair press is important, please support the website.

This piece is part of a content series on threats to independent media in Central Europe in collaboration with IPI.