There was a time when Hungarian buses traversed the Sahara where Mercedes buses had broken down

Around sixty years ago, Hungary made a very special entry into Africa. On the afternoon of 31 March 1963, an expedition was launched involving two Ikarus buses and two Csepel trucks. They set out from Dakar, the capital of Senegal, and travelled 20,000 kilometres, passing through Nigeria in their way to Accra, the capital of Ghana.

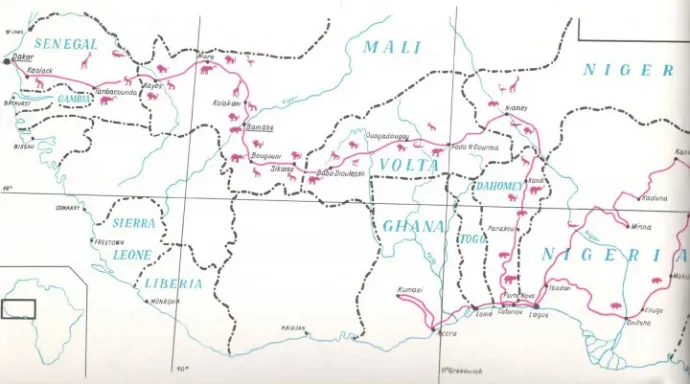

The route, as shown on the map below, led through eight countries. The terrain was not easy, with few paved roads, while temperatures were above 35 degrees Celsius almost everywhere, with frequent rain, not to mention the desert sand that could easily ruin the engines.

This was not the first tour of this kind, as the Czechs had already travelled 30,000 kilometres from north to south across the African continent with Škoda and returned to the Mladá Boleslav factory with valuable experience. The Hungarian Csepel company had already tested its vehicles in Tibet in 1956 under unique weather conditions. The mission actually ended on 23 October, so the mechanics and drivers had to spend several days idly and helplessly waiting to find out how they could return to the country in the midst of the revolution.

Ikarus had already sold buses to Guinea in the early 1960s, but now they wanted to show the locals how these buses could operate in extreme conditions. They had more confidence in demonstrating what they could do on site than in sending out brochures. Sixty years ago there was no GPS and one could only rely on Michelin's precise maps. The tour was not without dangers, as some of the more hostile tribes could have also attacked the Hungarian team. Still, as they later reported, they were generally received in a friendly manner. The French did not recommend the trip in their former colonial territories, saying that the famous Mercedes buses had not been successful on this challenging terrain and got stuck in the desert, so the Hungarians had better not go. (The Paris-Dakar rally was not held until 1979, and today, the rally is no longer run on the continent.)

This did not affect the determination and courage of the Hungarians, who specially adapted the vehicles for the desert and savannah conditions, for example, the windows were fitted with mosquito nets – mosquitoes and bugs were the most feared – and extra fans were installed to better withstand the heat. They also took along planks for building emergency bridges, and a rubber mat, which was essential for driving in the desert.

The yellow-and-black striped Ikarus 631, Ikarus 311, Csepel D-344 and Csepel AMG-450 trucks (nicknamed Red Arrow) set sail from a port in Poland. The crew flew under the guidance of Chief Engineer Ágoston Körmendy, head of the factory's pilot plant, and György Pallér, Sales Manager of the foreign trade company Mogürt, and met the vehicles again in Dakar. The vehicles were driven by János Varga, János Badacsonyi, Tibor Moldován and Mihály Tóth, all of whom were experienced mechanics and test drivers from the Csepel Automotive Factory.

The finishing touches were added in Senegal's capital, where they repaired minor damage sustained during the journey. Badacsonyi impressed the French company (Traveaux Publics) with the very first demonstration, as, according to reports, he exhibited extraordinary skill as he drove the Csepel over a bumpy, hilly and of course mostly sandy test track, which had previously only been completed by Berliet from France, Volvo from Sweden and Mercedes from Germany. Not only did the Hungarian team's performance attract the attention of the Hungarian press but also that of foreign journalists.

They set off from Dakar, and on the first day, they covered 182 kilometres, with their first stop being in Fatick. Temperatures reached as high as 36 degrees in the shade during their journey. A relatively short stretch followed the next day, and on the third day, the second of April, the convoy had 282 kilometres to cover between Kaolack and Tambacounda. This distance was a great test for both the vehicles and the men, as the laterite pavement was so grainy on this stretch that they had to leave a two-kilometre distance between their vehicles due to the stone dust that was kicked up. Also, frequent road closures meant that they had to take detours on the savannah bypasses, sometimes 20 or 30 kilometres-long, before they could get back on the main road.

The locals were shocked, as they had never seen buses like that before, and were even more impressed to see the Ikarus easily covered a steep, 12-metre downhill section. The buses and trucks could cross rivers reliably, even when there was no bridge. Sometimes, when the four-wheel-drive trucks were looking for the shallow section, crowds of up to a thousand people gathered to see how the experiment would end. The Hungarian convoy was often held back by heavy rain. After a thunderstorm, some sections of the road were closed, because if heavy vehicles drove on the wet, weak roads, they would sink up to the axle and make the roads impassable for a long time. There were several occasions when the rainfall caused at least 12 hours of enforced stoppages.

Sometimes they spent the nights in hotels, but they also had to sleep in the open air, often on top of the buses in sleeping bags. They parked their vehicles in a rectangular shape and could cook in the relatively enclosed area between them, with Tóth being the best cook among them. Minor injuries were apparently sustained; one mechanic was stung by a scorpion, and the local wizard from the village was called in, who poured a special substance on the swollen skin, spat on it and danced the bad luck away. The man was cured by the third day. According to reports, they saw a lion once and had more reason to fear the crocodiles inhabiting the rivers, but they were never attacked. However, they had to fight off monkeys all the time, as these animals would immediately pounce on their food.

According to Badacsonyi's 2002 interview in Veterán Autó Magazine, they were even able to provide technical assistance to stranded locals during the trip, who were mostly hampered by frequent belt breakdowns. So they often just hung the belt on the rear-view mirror and didn't put it in the boxes, because they suspected it would be needed soon enough. They were also able to buy ice in small villages, and because there were special compartments in their vehicles, they were able to transport it, so they never lacked water.

Sometimes they had to be clever, because at border controls it was found strange that the bus had a number plate beginning with the letters PR. In the end, the number plate got lost on one of the bumpier sections. This is how Badacsonyi recalled one incident:

"When they refused to let us through despite the gifts of flags and badges, our leader told them that PR stands for president and that we were taking the cars as a gift to their president. The border guards then saluted and let us through without a word."

Once, near Kolokani in Mali, they ran out of fuel and by the time they were able to get some, it was dark and they didn't get back to their companions until nighttime. They noticed that there were a lot of black men lying around the Hungarian camp. However, it wasn't a beating that made them unconscious, but the hidden stash of Hungarian cherry brandy they had found. Incidentally, the team had not taken any weapons with them, because they believed that the best weapon against any attack was the gas pedal.

The team successfully completed the expedition, returning home in August after 184 days on the road. The vehicles were again loaded onto ships and returned to the Csepel factory via Poland, where they were thoroughly tested and detailed analyses were carried out to see how well the parts could withstand the climate.

The management hoped that African countries would buy the buses and trucks. How much exactly the expedition itself boosted sales is not known. But we do know that while

- there were 1,298 lkarus buses sold in 1963

- in 1964, the figure rose to 2,060

- and in 1967, to 2820,

- while a year later sales exceeded 3,000 vehicles.

Truck sales also doubled within three years. In the desert of Mali, the Ikarus buses were the first to make it through the desert, coping even with 48-degree heat in the shade.

Ágoston Körmendy, the mastermind behind the tour, who also made the film footage for Hungarian Television, died in 2011, but not much is known about the other members of the mission.