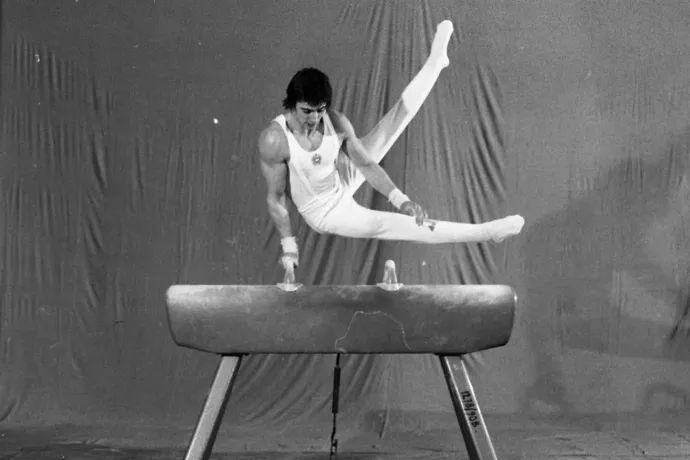

13 May 1973 was an important day for Hungarian gymnastics: it was on that day 51 years ago that Hungary won its first gold medal at the European Championships. This was not the only reason why Zoltán Magyar's victory on the pommel horse was special, but also because it was there, at the competition held in Grenoble, France, that he first performed the Magyar Travel, which no one had ever done before. While there were several innovations on the pommel horse at the beginning of the seventies, and the gymnasts started going beyond parallel movements, the movement tailored to Magyar was something nobody else was able to perform.

Magyar, who had grown up in Budapest's Ferencváros neighbourhood, had already tried circling above the pommel horse at the 1972 Olympics, but at that time, by his own admission, he was not yet ready to perform the move at world class level – neither mentally nor physically. The particular difficulty of the circuit was that he put his hands between the two handles as he moved from one end of the horse to the other.

He fell off the apparatus in the qualifier, but was successful at performing the routine in the individual compound final, scoring high points. His real breakthrough, however, came in 1973, when he was able to perfectly execute what he had been preparing to do. It was an innovation that nobody could emulate for years, even though the Japanese, a major power in the sport, had filmed his technique and later tried to pick up on the nuances.

At the time, a Soviet sports paper wrote that they had previously thought that Poland’s Wilhelm Kubica was the only one who posed a threat to the two Soviets, Andrianov and Klimenko. The Pole did beat the Soviet aces, but he didn't stand a chance against the 19-year-old Magyar, who was the only one to score above 19 points (19.05), while the Pole's performance was rated at 18.8.

“His impressive routine testified of an amazing sense of balance”

– one of the Soviet coaches said. The adjective "acrobat" was also used alongside his name. After the European Championships, Magyar was invited to Brazil for a demonstration tour to showcase his skills. (While there, he lost his first European gold medal, and he didn't get it back until later.)

After he performed his routine, the French sports newspaper L'Equipe wrote that it contained more transpiration (sweat) than inspiration. László Vígh didn't fully agree with this statement, and said that a lot of practice had gone into Magyar being able to move between the handles with such elegance. Vígh, who graduated as a specialized coach from the College of Physical Education (TF) in 1968, was himself a gymnast and an excellent theoretician. He argued that Hungarians were not technically inferior, but their fitness needed to be improved, and he attributed the mistakes they made to their inferior stamina. He explained the key to performing the Magyar Travel to his other students as well, but most of them fell off the horse. Magyar's deltoids, pectorals, shoulder muscles and triceps, however, were all above average.

A year later, Vígh shared a real trick of the trade in his 15-page treatise in the TF magazine. The piece was richly illustrated with photos and diagrams to aid understanding. According to this, they used two types of pommel horse in the exercises, one more slippery than the other. Magyar wasn't able to go through with the routine on the slippery one, because he was unable to properly support himself, while he could execute the envisaged movement perfectly eight out of ten times on the other one. Vígh also admitted that after a while – out of simple defiance – Magyar refused to practice on the more slippery horse.

The always critical coach also made no secret of the fact that Magyar had made a mistake in his routine when he won his first gold, but since it wasn't anything glaring, and his routine was so difficult, the judges had no intention of marking him down.

At the 1974 World Championships in Varna, Magyar performed a perfect routine and became the world’s best. He also won the European Championships in 1975, but made sure to perfect one more element prior to the Montreal Olympics – so that in case someone else had figured out how to perform the Magyar Travel, he would still be one step ahead of the rest of the world. This was the spindle.

In 1976, many thought he would receive 10 points for his routine, as did Romania's Nadia Comăneci in the women's event, but in the end, the scorekeepers were not so generous with Magyar. Nevertheless, his score of 9.9 meant that he still finished with a tenth better score in the final than the Japanese Kenmocu, the Soviet Union's Andrianov and East Germany's Nikolay and won his well-deserved, first ever Olympic gold medal, which was also the first gold medal for the Hungarian delegation that year. According to recollections, went to the pommel horse he was pale, but sat down pleased afterwards. He said he had never been as nervous as he was then.

His winning streak continued after the Olympics, and he remained undefeated at both the European and the World Championships. According to Vígh, he performed his best routine in 1977. At the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, the Soviets wanted to have him declared winner in a tie, but the captain at the time, Dezső Bordán firmly refused this. He didn't care about incurring the disapproval of the higher echelons of the party, and simply refused to allow professionalism to be tarnished. Team leader István Buda said that if they dared to give less points to Magyar than he deserved, the Hungarian delegation would pack up and go home.

Then, in the qualifying round, both captain and athlete had to endure dramatic moments, because the judges deducted 75 hundredths from him without a valid reason, leaving him in fifth place. The Hungarian leadership immediately protested, which was upheld, and the 75 hundredths were added to Magyar's score, which put him in first place right away, thus allowing him to start the final from the top position.

Magyar's routine in the final earned him 10 points, which was the maximum amount one could receive back then. The judges either overlooked one of his minor mistakes or didn't notice it. Decades later, when speaking about that day, he said that he wanted to stay on the pommel horse at all costs, because it would have made him look bad if he had made a mistake at his last competition. It was his head, not his hands that helped him out in that tenth of a second. Dityatyn and the two East Germans, Nikolay and Brückner all received a tenth less points than him. That competition, which was his last, was the crown on an unparalleled winning streak.

"I just can't take the mental pressure of big tournaments anymore. I'm retiring. There might be some who'll say that I’m running away. I don't want to argue with them, but perhaps even they can understand someone wanting to go out on top," he said after winning the gold medal and defending his title. To this day, he's the only Hungarian gymnast who managed to defend his title of champion.

Another statement from 2013 captures his character well: “I got ten points for that, even though it's well known that there is no such thing as a ten-point routine. But it was a way of seeing off a retiring gymnast, and the judges granted me that honour.”

According to Vígh, the first to replicate Magyar's 1972 routine was a Chinese gymnast in 1981. The fact that an Olympic final is now unimaginable without the Magyar Travel shows very well just how timeless his innovation was.

After he retired, Magyar earned a degree in veterinary medicine and was elected president of the national gymnastics federation in 2011, a position he still holds at the age of 71. In 2012, he was inducted into the ranks of the immortal gymnasts of the world for changing the sport. In 2015, he was elected "Athlete of the nation" in Hungary.

Sources used: The book “Az első Vándor”, and Virtuális Sportmúzeum.

If you enjoyed this portrait of an extraordinary Hungarian, and want to make sure you don't miss similar stories in the future, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!