There's a strange-looking structure rusting away just a few kilometres east of Moscow, at the Russian Air Force's open-air aircraft museum in Monino. Its body resembles the remains of a giant turtle, but when photographed in winter, it looks like the wreckage of a stranded Walker from The Empire Strikes Back. This is the Bartini-Beriev VVA-14, a Soviet prototype built in the 1970s and intended to perform an unusual task for an aircraft: hunting down US nuclear submarines. More interesting than the plane, however, is the fact that its designer, Robert Ludvigovich Bartini – or Roberto Oros di Bartini – who most of the world thought had Italian noble roots, was in fact Hungarian-born.

Bartini’s amphibious airplane

The VVA-14 was inspired by the US Polaris ballistic missiles. When the US introduced this weapon on its submarines in 1961, in the middle of the Cold War, the USSR's command staff was immediately alarmed by the thought that America could now launch nuclear missiles while approaching the Russian coast. The idea of a submarine-hunting aircraft was born, and in the 1960s, work began at the Beriev Design Bureau under Bartini’s leadership.

The designer envisioned a universal aircraft that can operate both as a conventional airplane and a seaplane, but can also take off from a fixed position. This is what the VVA in its name stands for, it's an abbreviation for Vertikalno-Vzletayuschaya Amfibiya, or "Vertically Ascending Amphibious Aircraft". The number 14 indicated the number of engines, the idea being that the VVA-14 would have flown horizontally with its two large engines, and with 12 smaller engines working during the vertical take-off.

Bartini envisioned three prototypes, the first for aerodynamic tests, the second to be used for in-place take-off, and the third one would have included a submarine-hunting system. In the end, only the first two prototypes were built, and only the first of these ever flew, meaning that only conventional flight tests and tests of the seaplane mode were carried out, and the in-place take-off was never tested. The first prototype, however, underwent several modifications: its catamaran-like fuselage had two pontoons (when the retractable undercarriage was not lowered) and Bartini tested them in both rigid and inflatable versions. The VVA-14 was not small for a fighter aircraft: it was 26 meters long, had a wingspan of 30 metres and weighed over 23 tonnes when empty. It could fly at speeds of up to 760 km/h, at altitudes of up to 10,000 metres, and had a range of almost 2,500 kilometres. Its shape quickly earned it the nickname Zmey Gorinich, the name of the three-headed dragon of Slavic folktales.

The first flight of the prototype took place on 4 September 1972 on a conventional runway, followed by several tests in the following years. The development of the aircraft was slow and expensive due to its special requirements, and the engines necessary for the second prototype were never completed. In addition, other types of missile defense equipment was being developed and it was slowly becoming clear that the aircraft would never fulfill the purpose for which it was designed. For this reason, Bartini took the development in a new direction: he wanted to see how the VVA-14 could be used as an "ekranoplan", an aircraft that could fly a few metres above the surface of the water, taking advantage of the cushion effect.

Bartini didn’t live to see the results of these tests: the designer died in 1974 at the age of 77, which sealed the fate of the VVA-14. The second prototype was dismantled, the first one was used for test flights for a while (it was a great help in the development of the later ekranoplans), and after 107 flights and a total of 103 hours of flight time it was retired. In 1987, the prototype was moved to the Moscow museum of the Russian Air Force, but for unknown reasons, the machine arrived damaged. The museum's director told CNN in 2021 that it would cost at least $1.2 million to refurbish the VVA-14, but that money was not available for this single aircraft, no matter how special. It's been sitting in a corner of the museum ever since, with a few pieces of it scattered around it – its distinctive shape recognizable even on Google Maps.

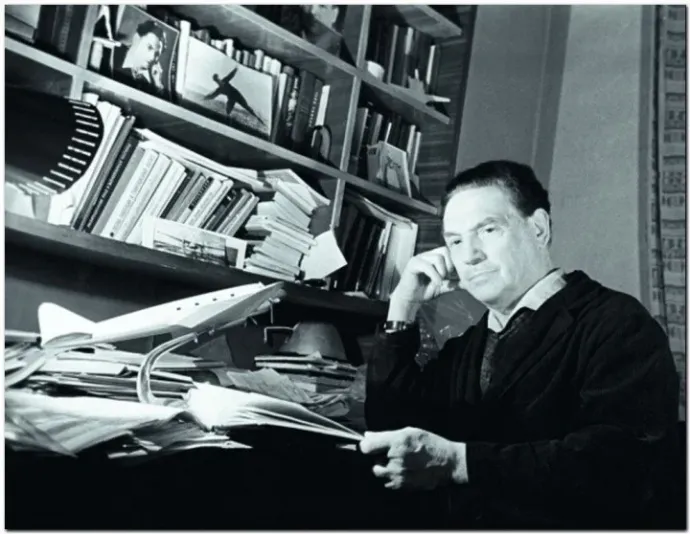

The mysterious Soviet Italian, who’s actually Hungarian

The CNN article also quoted Andriy Sovenko, a researcher of Soviet aviation history, who cited Nikolai Pogolerov, whom he had met in person. Pogolerov was Bartini's deputy during the design phase of the VVA-14 and he described his former boss as an unconventional-minded visionary. "He seemed to have come not from our time, but from another age – some might have called him an alien," Sovenko said, quoting Pogolerov, who said Bartini had many far-fetched ideas, many of which never materialised. The article, although it features many interviewees, makes one mistake: it consistently identifies Robert Bartini as Italian – when he is most certainly of Hungarian origin.

On the other hand, any mistake about Robert Bartini is understandable and forgivable. He is one of the most mysterious figures in the history of aviation, about whom little information has leaked from the Soviet Union, and much of the available data is false. Bartini was a great confabulator and, according to one of his biographers, he never told the same story twice. The reason for this is not entirely clear. Some of the deceptions probably served Bartini's own interests, but it is also possible that he wanted to protect his remaining family in Hungary, so that no one would get in trouble because of the communist relative, who was later awarded the Order of Lenin and the Order of the October Revolution.

The uncertainties begin with Bartini's birth and the name Bartini itself. The Italian name – Roberto Oros di Bartini – hides the clue to his roots: 'Oros di' actually refers to the Orosdy family, as the engineer was born Róbert Orosdy. He was most probably born in 1897, the son of Lajos Orosdy, a border policeman, but he was born out of wedlock and was raised by relatives in Miskolc until the age of three. A few years later, however, the man's wife agreed to the boy taking Orosdy's name, and father and son could met again. Róbert's birthplace was either Nagykanizsa or Fiume, (today's Rijeka in Croatia) but the grandson of Lajos Orosdy, Béla Orosdy, whom we managed to reach was not sure which one. "My grandfather lived in Nagykanizsa, but when he was promoted, they moved to Fiume, so both are possible," Béla Orosdy said. Nagykanizsa is perhaps more likely, as the move to Fiume took place in 1905.

So Róbert Orosdy was neither born Italian, nor was he born noble. "Our family is of Jewish origin, my great-grandfather was Kossuth's secretary under the name of Adolf Schnabel," Béla Orosdy said. – The Hungarianised branch became Orosdy, but only one side of the family could be called noble: a close relative of Lajos, Fülöp Orosdy, was made a baron in 1905." But Béla Orosdy has no doubt about Róbert Orosdy being a member of the family and the son of Lajos by blood: “This is clear from my grandfather's will. He wrote at length and with emotion about Róbert, whose choices in life he did not approve of.”

But then where does the name Bartini come from? There are several explanations for this as well. Some sources say that Róbert's biological mother committed suicide after the birth of the child, but others, including Béla Orosdy, say that she later married a man named Bartini. (The identity of the mother is not clear either, as she is sometimes described as the daughter of a poor noble family, but Béla Orosdy's grandmother told him that she was a low-ranking employee of the Hungarian governorate in Fiume.) So one explanation is that Róbert Orosdi later took his stepfather's name, and probably added “Oros di” to his name at the same time.

The other answer is much more unusual. In the October 2018 issue of the magazine, BBC History's Béla Kálmán wrote a lengthy article about Robert Bartini, in which he quoted the legendary aeronautical designer's grandson living in Moscow. According to the grandson, the coat of arms of one branch of the Orosdy family features a red and a black bird and a Latin motto: "Bella avis rubra terrorem infert nigrae", meaning "The beautiful red bird defeats the black one". The grandson says that Orosdy used the initials of the motto to create the name Bartini, which also became the name he used in the communist movement. This good-sounding story has not been confirmed by other sources (and there is no such bird among the Orosdy insignia on the web), but the constructor's epitaph is certainly a reference to this story of origin:

“In the land of the Soviets, he kept his oath and dedicated his life to making red planes fly faster than black ones.”

Genealogist Krisztián Skoumal sent us a birth certificate entry, which presumably records the birth of Róbert Orosdy, and two others, which indicate his relationship to Lajos Orosdy. According to these, the child was born on 14 May 1897 in Nagykanizsa under the name Ferlesch Róbert Frigyes, an illegitimate child. His mother, Mária Ferlesch, was a 20-year-old self employed woman from Nagykanizsa, born in Villach (Austria). In 1904, Róbert was adopted by Dr. Lajos Mihály Béla Orosdy, and the boy was called Orosdy from then on.

The path to the order of Lenin

The sources all agree that Róbert Orosdy served in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy's army in the First World War, and had most likely become interested in flying by then, probably due to the aviation advertising events he had witnessed previously. In 1916 he was captured by Russians and sent to an internment camp in Siberia. It was here that he met Máté Zalka, and likely became a convinced communist as a result. When he was released in 1920, he was transported to Italy because he was thought to be of Italian nationality. There he obtained his pilot's license and a degree in engineering from the Milan Technical School, although BBC History notes that the existence of the diploma is not confirmed. It is believed that he was spying for the Soviets during this time, and when things began to heat up around him in 1923, he moved to the Soviet Union, this time of his own accord.

By this time, he had even become uncomfortable for his family. "It was hard for my grandfather to accept that Róbert had gone to communism and embraced its values," Béla Orosdy said. Apart from the ideological difference, this could have been a problem because there were times in the 20th century when a Bolshevik relative could have brought trouble on one's family. As has already been suggested, it is quite possible that the many uncertainties around Bartini are partly due to this, and that he might have made a conscious effort to hide his roots.

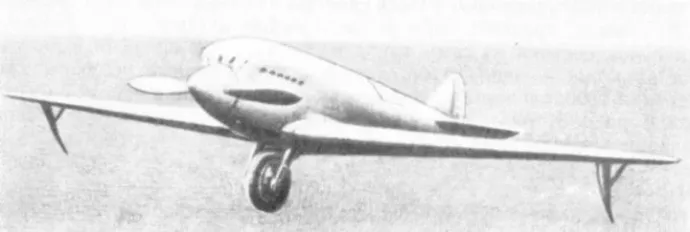

In the Soviet Union, he was already living under the more Russian name of Robert Ludvigovich Bartini, and became one of the most inescapable figures in Soviet aircraft design. According to a BBC History article, in 1928 he was already head of the experimental department of seaplane production in Sevastopol, and two years later, on the recommendation of Marshal Tukhachevsky, he was appointed chief designer at the Experimental Institute of Civil Aviation. It was there that Bartini designed the groundbreaking Stal-6 (aka Steel-6) experimental aircraft, which featured some unusual features such as the unicycle retractable landing gear.

The Stal-6 was significantly faster than the Soviet fighter aircraft of the time, so an attempt was made to convert it into a fighter jet under the name Stal-8, but this did not happen in the end. However, the Stal-7 high-speed passenger aircraft was developed, and later the DB-240 long-range bomber as well, which was used in World War II. This was not Bartini's design though, as he was in prison once again: the Stalinist purges of 1938 had caught up with both him and Tukhachevsky.

Two years later he was sentenced to 10 years in prison, which he actually served, and was only released from the Gulag in 1948. However, he had an easier time than most prisoners: he was sent to a sharashka, a special purpose camp for important people, where prisoners were better cared for and could work in their own profession. Bartini was sent to sharashka CKB-29 (for the first years in Moscow, later in Omsk), where the Soviet greats of aircraft design were gathered, such as Sergei Korolyov, who later developed Soviet space rockets, and Vladimir Petlyakov. The team worked under the leadership of Andrei Tupolev and by the early 1940s had created the Tu-2 bomber. Bartini was later given his own office in Sharashka and designed transport aircraft. In the years after his release, he worked for several design firms, designing supersonic delta-wing aircraft and nuclear bombers as well.

He was rehabilitated in 1956 and was awarded the Order of Lenin. The idea of ekranoplans was already on his mind in 1962, when he designed the MVA-62, which would have functioned as both a conventional aircraft and an ekranoplan – it was his experience in designing this that he used when he joined Beriev in 1968 and started designing the VVA-14. The submarine-hunting amphibian eventually became the Hungarian-born designer's swan song. His unexpected death was caused by arrhythmia.

He left behind a strange will, his former close colleague Leonid Fortinov told TopWar.ru. that Bartini had requested that all his works be put in a metal box and opened in three hundred years. The engineer's last wish was not carried out. “After Bartini's death, two huge bags of paper remained: calculations, drawings, formulas, notes. 'No one started boxing them up,' Fortinov said.' From time to time, colleagues fought with internal inspectors who kept demanding that they get rid of unnecessary papers. And when people who knew Bartini retired, his papers were simply burned.”