The Hungarian doctor who was mistaken for Mengele, the feared Nazi doctor, and who translated Winnie the Pooh into Latin

August 08. 2022. – 04:59 AM

updated

Sándor Lénárd is not a household name in Hungary, even though the adventurous writer, linguist, musician and doctor gained worldwide fame a few decades ago. He had the unusual idea to translate Winnie the Pooh to Latin, and his work became a popular textbook in several countries, and even made it to the New York Times’ bestseller list. Although Lénárd was in many ways like Albert Schweitzer, at one point, he even had to deal with being mistaken for the infamous Nazi doctor, Josef Mengele.

Lénárd grew up in a Jewish family. Since his father worked for transportation companies, at the age of nine he moved to Fiume (modern-day Rijeka, Croatia), and a year later, in 1920 to Vienna. His talent for languages was obvious even at this early age: in high school he was translating the works of Hungarian poets to German, while working on the translation of Goethe’s Faust into Hungarian, as well as writing his own poetry in German. In 1928 he was admitted to the Medical University in Vienna. He later said that he chose medicine because the administration for registering for other faculties was too complicated. He spent 14 semesters at the medical faculty, but there is no proof that he ever graduated. Of course, this did not stop him from practicing medicine later on. After university he was a teacher in Austria, but didn’t stay too long. Following Austria’s attachment to Germany in 1938 and the growing antisemitism, he fled to Rome.

Three miserable years followed. He was practically homeless, often went hungry, and took odd-jobs to survive. He worked as a kitchen help, but once he even played the piano in exchange for a meal. During this time he continued learning more languages. Other than Italian, he learned Spanish, Norwegian and Dutch, so eventually he was able to make some money from interpreting and translation as well. He even worked as a ghost writer and wrote a few doctorates for others. He was equally at home in medical subjects and topics related to art history or archaeology. He spent hours upon hours at libraries, and for a long time believed that the only way to avoid fascist propaganda was to stay away from materials published more than two hundred years earlier.

During the Second World War he was part of the antifascist movement and helped hide British officers from the Germans. After the war he worked for the U.S. army as an anthropologist: he exhumed the bodies of fallen soldiers and put their skeletons back together. In 1947 he became the doctor at the Hungarian Academy in Rome, where he met several members of the Hungarian literary elite of the time. Among others he became friends with Sándor Weöres, Tibor Déry and Ferenc Karinthy. They unsuccessfully tried to talk Lénárd into moving home. The doctor continued publishing German poems and various translations, and in 1952 eventually – for fear of a new world war breaking out – moved his family to the faraway country of Brazil which he considered safer.

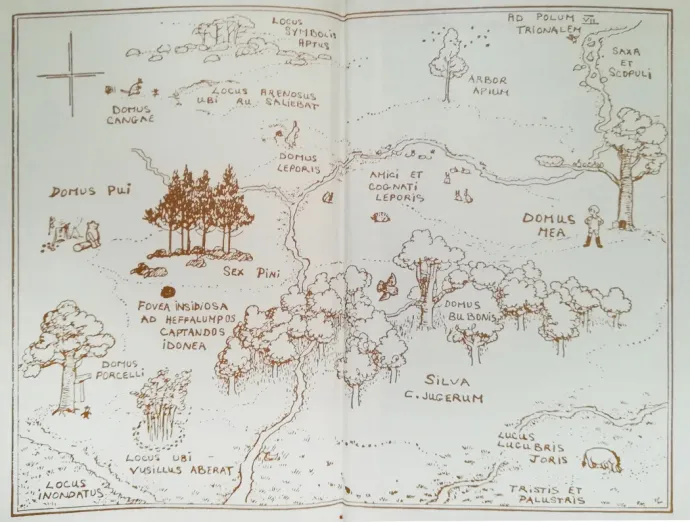

Eeyore speaks like Cicero

The Lénárds didn’t stumble upon paradise and their new life began quite adventurously. His career in Brazil started in a lead mine where he worked as a medic. Although they didn’t recognize his medical degree, he was a GP, pediatrician, trauma surgeon and obstetrician – all in one. The poisonous lead was destroying the miners’ health fast, so Lénárd sent anyone he could to a one- or two-month medical leave and encouraged them to leave the mine. This did not make him popular with the owners, so barely six months after arriving, he left as well. In these few months, however, he got the idea for translating Winnie the Pooh into Latin and he couldn’t get it out of his mind. French mining engineers had asked him to teach their daughters English, history, mathematics and Latin. He had successfully used Winnie the Pooh for teaching English before. Since his students struggled with Latin, Lénárd thought that Milne’s book might be of help with this language as well. He started working on the translation right away, and the first few chapters were an instant success.

“The young ladies received the words of Cicero gladly – as long as they heard them spoken by Eeyore.”

– he wrote in his autobiography. It wasn’t the first time Lénárd reached for Winnie the Pooh for help. In 1943 he used it to teach a member of the Italian resistance English, so he could communicate with the American allies. He finished the Latin translation when they moved to São Paulo, and – using a postmodern method – added some guest texts to Winnie the Pooh, thus making the book’s protagonists quote classic texts at times.

"I was reading Horace and Petronius, Apuleius and old Cicero – all of whom I used to find so boring before – slowly and with infinite delight. They have all obligingly provided words and phrases for Mr Milne's zoo," Lénard wrote.

He first self-published Winnie the Pooh’s Latin translation entitled Winnie ille Pu in 1956 in just 110 copies. He sent the books to linguists, classic philologists, libraries and various publishers, and many were excited to see the Latin version of Winnie the Pooh, which had been becoming an almost antique piece. This gradually snowballed: at first a Swedish publisher printed two thousand copies of Lénárd’s translation in 1959, and then they ordered two thousand more. Then a publisher from Stuttgart printed 50 thousand copies of Winnie ille Pu, and the book slowly began taking off in English-speaking countries as well. One hundred thousand copies were printed in London, and the book made it to the New York Times’s bestseller list. To this day it is the only foreign-language book to have accomplished this.

Lénárd’s book made Latin popular. Some argued in vain that a child can never know enough Latin to read such a book, and an adult would never be interested in Winnie the Pooh’s story. Literary historian László Szörényi mentioned in an interview that an American professor once told him how thankful he was that the Hungarian author saved the teaching of Latin in New York state – as this is why he was still able to learn it. “The second edition of the Latin Winnie the Pooh had just been published in two hundred and fifty thousand copies. It took the book market by storm, and every parent and child wanted to read Winnie the Pooh in Latin, so the language was put back in the high school curriculum” – Szörényi said.

Winnie ille Pu did not get published in Hungary until much later, in 1992, where it was also used for teaching Latin. Nowadays one can only find a few scattered copies in antiquarian bookstores.

One more question about Bach?

It was Winnie ille Pu that brought success for Lénárd, but it was a quiz game that brought him financial security. In the program called “The sky’s the limit”, the players had to answer questions on a topic of their choice. Lénárd chose Johann Sebastian Bach, as he was a big fan of his music and knew it well. Week after week, the Hungarian doctor answered every single question correctly, which attracted the viewers’ attention to both the composer and to Lénárd. When he played, the streets were empty. He excelled even when he had to guess the piece based on a ripped up sheet of music. Not only did Lénárd provide the name of the piece, but he sat down at the piano and played it on the spot. His Italian wife Andrietta later said that these appearances were very taxing on her husband, so he stopped at around 200 000 Crusiedos (this was worth around 2500 USD at the time). He used his winnings to purchase a pharmacy near the jungle, in Donna Emma. Lénárd lived a quiet life and treated the local Swabian settlers and botokud Indians free of charge, and at times – just like Albert Schweitzer used to do in Africa – played classical music in the local church. Starting in the 1960’s he focused more on writing. He wrote a few autobiographies, but being a polyhistor and a keen cook, he also wrote a book about Roman gastronomy.

He’s a doctor and speaks German? Then he must be Mengele!

Probably the most absurd thing to have happened to Lénárd – who was of Jewish descent and had to move twice due to the spread of extremist views – was when, at the end of 1968, he was mistaken for the infamous doctor of Auschwitz, Josef Mengele. It was a former police interpreter named Erich Erdstein, who began suspecting that Lénárd was Mengele since the man going by the name of Alexander Lénárd was a doctor and spoke German, and even squinted half an eye – just like Mengele. Erdstein assumed that he must be hiding his wealth in the jungle. The fact that the scientist’s housekeeper was also German, and that she used to work at the Hermann Göring Works only increased suspicions. Erdstein got the police involved, but they were unable to arrest Lénárd as he was teaching a university course in the US at the time. He later commented on the incident with killer humor:

“On the night of December 16, thirteen men armed with machine guns surrounded my house with their cars and planned on capturing me at dawn. And they would have, if I had not been in Charleston at the time. So instead, they questioned poor Mrs. Klein again. They demanded that she tell them how she made the nuclear bomb (she does make excellent dumplings), searched the house and found a portrait of Bach (Hitler in disguise!), and a postcard with the handwritten text: “I will take care of the seeds for the flowers and the crops” (a secret, coded message). They looked in vain for gold and diamonds…”

An even steeper part of the story was when Erdstein, the fraud, ended up publishing an article in a German newspaper claiming that he had shot Mengele and included a photo of Lénárd. In response to this, the Hungarian scientist published the story from his perspective in Stuttgarter Zeitung. Although he takes a humorous approach in the article, people who knew him say that Lénard was traumatized by the smear campaign and his already poor health deteriorated even further.

When Lénárd died at the age of 62, in 1972, his life’s work was mostly unknown in Hungary. When his autobiographical work entitled “Valley at the end of the world” was published in Hungary in the 1960’s, he briefly became popular but later disappeared from the mainstream – even though just a few sentences of his writings will convince the reader that he was indeed a great writer. And one doesn’t even need to know Latin to see this.

If you enjoyed this story and want to make sure not to miss similar content in the future, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter! It's free and only takes a few seconds to sign up for!

Sources used in the article:

Magyar Napló, 2005, (17. évfolyam, 11. szám)

Kurír, 1990, 1. évfolyam, 124. szám

Magyarország, 1969., 6. évfolyam, 9. szám

Élet és Irodalom, 2010, 54. évfolyam, 11. szám

Siklós Péter: Budapesttől a világ végi völgyig – Lénárd Sándor regényes életútja

Berta Gyula: Egy magyar orvos, aki megtanította latinul Micimackót

The translation of this article was made possible by our cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.