What can we learn from the data on the Hungarian victims of Covid-19?

Since the start of the pandemic, more than 25,000 people fell victim to complications of Covid-19. The vast majority of them had underlying medical conditions that, in many cases, contribute to a more severe outcome of the disease, though this is not specific to the coronavirus; the prognosis for any acute illness is worse for chronically ill patients. The official statistics on the pre-existing medical conditions of Covid-19 victims reflect the poor general health in Hungary and reveal that hospitals' administration is far from standardized.

A returning staple of the press conferences of the Hungarian government's Coronavirus Task Force is that the people dying of the coronavirus are "mostly elderly, chronically ill patients." In part, that is true, but the third wave, characterized by the prevalence of the Kent variant, saw more younger people affected harder by the virus or even dying, even without any underlying illnesses. Still, the Hungarian statistics show that a vast majority of the first 25,000 victims of the pandemic in the country had one or two comorbidities.

To interpret that, we have to define what we call a "chronic illness," which is not entirely clear. The textbook definition is that

A chronically ill patient is anyone who sustains a disease for more than six months.

Infectious disease expert András Csilek, the Chairman of the Hungarian Medical Chamber's Borsod-Abaúj-Zempén county chapter, says that in daily practice, they classify diseases as chronic if their root causes cannot be eradicated, but can be treated. Such a chronic illness, for instance, is hypertension: Blood pressure can be set to proper levels with medication, but its root cause, arteriosclerosis, cannot be fixed.

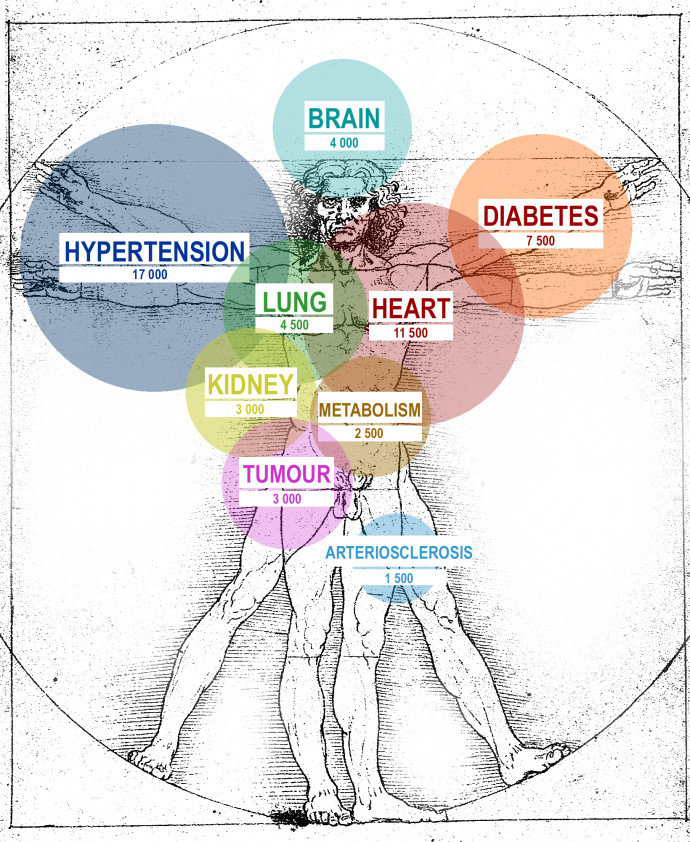

Until 18 April, 25,184 Covid-related deaths occurred in Hungary; the chart below contains the most frequently mentioned comorbidities or the organs affected by these comorbidities. As the statistics often note more than one underlying condition in individual cases, the total adds up to more than 25,000.

As we browsed the data published on koronavirus.gov.hu, we noticed that the denomination of illnesses is not standardized; many times, the same comorbidities were mentioned under different names, even disregarding the typos and other spelling errors. Csilek says this is no surprise: "Hospitals must provide such an immense amount of data that required them to allocate medically qualified teams to enter them. Still, they cannot be aware of every possible technical term; hence there are sometimes differing denominations. There is such a thing as the ICD, the international classification of diseases and health issues, but not everything can be coded. The same condition sometimes gets classified differently; heart failure, for instance, can be described in a number of ways. Medical language has become a mixture of Latin, Greek, Hungarian, and English, which can also lead to confusion. Calling a disease differently can also come down to cultural differences. If an older colleague says "bárzsing" in Hungarian, they only get confused stares from younger coworkers, even though it used to be a common medical term for the oesophagus."

Csilek also noted that there were no other diseases before the coronavirus where doctors had to draw up such detailed reports of the comorbidities. Since it is unclear what underlying conditions are relevant, hospitals report everything they find when a patient gets admitted or what they learn from the anamnesis.

Csilek thinks that the underlying conditions of Covid-19's victims correlate to what is typical of the general population. "A large part of those who died were of old age, and the most frequent underlying conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular problems are quite common with those above 40; therefore, it is no surprise that the statistics look as they do. Covid-19, though, does not pick and choose: being healthy does not mean that its chance of killing you is zero."

The expert illustrated how an underlying condition might affect the outcome of a Covid-19 infection with an example: "If you ask a 70-kilogram and a 120-kilogram person to run on the track, the first one might be able to run a kilometre, and the other would be out after 200 metres because his body is under larger stress. Covid-19 and the inflammations it causes also stress the system, which needs to release energy to fight back. In the case of a patient with a chronic kidney or liver disease, that becomes much harder, just like it's harder to maintain the oxygen supply of vital organs when lung tissues are damaged. A completely healthy individual may not even notice a temporary drop in their lung capacity."

A US study suggests that the risk of death is the highest with Covid-patients who were previously diagnosed with hypertension, diabetes, a heart condition, cancer, or chronic kidney failure. Chronic kidney disease increases the risk of death by threefold, primarily due to immunological problems. The risk doubles with heart conditions, while diabetes and tumours grow the chance of a fatal outcome by 50 per cent.

Why is the data fuzzy? Our methodology

The detailed data about coronavirus-related deaths on the official government website koronavirus.gov.hu is not searchable, and the dataset cannot be downloaded in a single file. The only way to harvest the data is to go page by page, copying the data of 50 cases at a time. At the time of writing this article, there were 504 pages. The dates of the deaths are unavailable, and victims are only marked by a number. Diseases do not only appear under different names (such as the Latin denomination or several different Hungarian variations); spelling mistakes and typos also make assessing the data more difficult. There are 65,000 different comorbidities assigned to the 25,000 victims, we cleaned the data to the best of our abilities, but our numbers are only approximate.

The general health of the Hungarian population is not particularly great, and the country usually ranks rather badly in studies comparing health in the 37 OECD member states. In 2017, Hungary was only second after Lithuania in the number of deaths caused by cardiovascular problems (575 deaths per 100,000 people). These appear a lot in the coronavirus mortality data too: two-thirds of the victims were diagnosed with hypertension (which is the most frequent comorbidity in Hungary), and 44 per cent had some type of heart condition. We must stress that there is a significant overlap between the two groups.

The third most frequent underlying health condition among the Hungarian Covid-victims was diabetes; at least 33 per cent of the deceased were diabetic. Csilek emphasized that diabetes does not only increase the risk because it is often accompanied by hypertension and kidney problems, but also because it induces complex immunological problems. The compromised immune system has a tougher time fending off coronavirus.

Hungary is in the top 10 countries most affected by diabetes, and the same is true for metabolic disorders. We are second after Mexico in mortality caused by liver failure. The rate of respiratory diseases is also high; Hungary ranked fourth four years ago.

The expert says that the coronavirus mortality statistics may reflect the general poor health of Hungarians. "While there are differences between Hungarian and Western hospitals, I do not want to believe that we would be worse at healing, patients are getting the same medications, and they are connected to the same kind of ventilators as anywhere else. These numbers are no accident if we do not exercise and just eat all day.

Coronavirus is no different from any other acute illness; even salmonella can defeat people if they have other health conditions."

Csilek says that they should pay special attention to obesity (mentioned at 5% of the victims) as it puts patients in the high-risk category. "It is a touchy subject since it is difficult to define obesity as a disease; diagnosis doesn't work as it does with hypertension. Few people go to the doctor over it, and it hardly makes it onto the anamnesis, only in extreme cases. But, surely, we underestimate obesity's role in cases turning more severe."

According to the 2017 OECD survey, 30 per cent of the Hungarian population is considered obese, even more extremely obese.

One could say that Hungary is Europe's fattest nation.

Alcoholism also gets underrepresented in the statistics; there are only 123 mentions. If an estimate by well-known addictologist Gábor Zacher is to be believed, there are 800,000 alcohol addicts in Hungary, and based on that, alcoholism should show up 10-15 times more in the data than it does. This low number, of course, could be attributed to the latency that is typical of alcohol problems, even if the organ failures specific to the disease do get identified.

We also asked the expert why dementia can increase the mortality risk of Covid-19, as it is not usually associated with the failure of vital organs. Csillek says dementia may not alter how the infection itself plays out, but it can cause practical issues that contribute to a patient's turn for the worse. For instance, disturbed consciousness may disable the patient from recognizing that they have fever or shortness of breath.

The chart above shows the ratio of patients who died with no comorbidities or whose data is incomplete. From last November to this March, there were several days when no deaths occurred without comorbidities; however, after 10 March, there is a noticeable spike. There have been four times as many deaths occurring with no underlying health conditions as there were in the period before.

Recently, this ratio has increased significantly, reaching as much as seven per cent on some days. Not even researchers know what the exact cause-and-effect relationship is behind Covid-19-related deaths, but they usually attribute this spike in the mortality of patients with no underlying health conditions to the Kent variant of SARS-CoV-2, which was the dominant strain spreading in Hungary during the third wave.