Are sexual minorities the 'new migrants' of Hungary?

Recently, there has been more and more political censuring centered around the issue of sexual minorities. Given current international trends and Poland’s presidential election this year, it may be that we aren’t just witnessing some random flare-up, but rather the lead-up to 2022 (the year of Hungary’s next parliamentary elections), and this will be one of the central campaign issues. This article delves into the background of the matter.

The flying of rainbow-colored flags and their removal. The shredding of books on the one side and their procott on the other. Psychologists rebuking one another and the collection of signatures both for and against. A political smear campaign against a convention on combating violence against women. A law abolishing the legal recognition of transsexuals. The labelling of gay people as pedophiles.

If you feel that gender and LGBTQI have been all over the news lately, you are not alone:

the topic of gender roles and sexual minorities has been slowly making its way to the center of public discourse. Although we have often seen various parties and groups stigmatize these issues for political gain, there are a number of signs indicating that this time it’s not just about some story propped up by a few marginal characters that will blow over in a few weeks.

Right-wing populists all over the world are finding this to be a fertile ground for gathering votes. Most recently this was observed with the open attack on sexual minorities in a campaign launched by Poland’s Law and Justice party – a party whose political views closely line up with Orban’s. The 2022 Hungarian parliamentary elections are fast approaching, and after the dominant issue of 2018, migration, Fidesz may be in need of another „us and them”-type of juxtaposition. Though numerous and diverse, the worldviews and social movements that the right shoves under the umbrella term „gender ideology” are the perfect candidates for the job.

This article was originally published on 21 October 2020, the translation was contributed by Dominic Spadacene.

Since the original publication, the Hungarian Parliament had adopted a bill on Tuesday barring non-married people from adopting children unless they acquire a special permit from the Minister for the Families, effectively closing the only available loophole for same-sex couples to have children and shutting the door on hundreds of singles as well – according to the Hungarian Statistical Office's 2018 report, approximately 10% of eligible, vetted prospective adopters are not married.

The explanation attached to the bill claims that the reason for this is to ensure adopted children end up in a "stable environment," but speaking to Telex, Tamás Dombos, the leader of LGBTQ organisation Háttér Társaság, said it's clear the bill aims to shut the door on same-sex couples looking to adopt:

"It seems that informal and unlawful pressuring did not work, as the experts working in adoption only cared for the interests of the children, and if a same-sex couple was found to be right to adopt, they approved. Until now, professionals were in charge, but from this point forward, Minister Katalin Novák will call the shots over which unmarried people get to adopt."

Also on Tuesday, the the Parliament passed an amendment to the Fundamental Law that proclaims “children's right to a Christian upbringing and an identity corresponding to their birth sex,” while also making a constitutional declaration that “the mother is a woman, the father is a man” to drive home the point of the already existing constitutional restriction of the family's legal definition, which assesses that a family is based on the consensual marriage of a man and a woman, banishing even the possibility of same-sex marriage from the Hungarian legal system.

Commenting on this, Amnesty International, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, and Transgender Europe have issued a joint press release condemning the provisions curbing the rights of and stigmatizing sexual minorities.

"Today is a dark day for the Hungarian LGBTI community, for human rights, and for everybody who holds human dignity and equality important. These homophobic and transphobic regulations are the new chapter in the Hungarian government's crusade against LGBTI people."

They expressed concern for the health and safety of Hungarian trans children and adults and called on Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the European Commission to include these developments in the Commission's upcoming rule of law report and have it reflected in the ongoing Article 7 procedure against Hungary. (ZK)

More and more mudslinging

The shredding of the children’s storybook and the events following it is just one example of the LGBTQI issues closely covered by the media that has rendered society much more polarized.

The most recent public rally on the topic of gender and homosexuality began last year with a famous statement made by László Kövér, when the Speaker of the National Assembly expressed the idea that homosexual couples who wish to adopt a child are morally no different than pedophiles. Shortly thereafter, Fidesz representative István Boldog made international news by announcing a boycott of Coca-Coca in protest of the gay couples displayed on its posters.

Earlier this year, the Istanbul Convention on preventing domestic violence, considered to be a „Trojan Horse for gender ideology” in Fidesz circles, had been described by Minister of Justice Judit Varga as political hysteria. The government has had no intention on ratifying it for some time now. It was right in the middle of the first wave of the coronavirus that Parliament triggered a public outcry when it voted to pass a law making the legal recognition of the transgendered impossible – as if the nation’s leaders had nothing more important to do than to pick on a sexual minority made up of at most a few thousand people.

During the summer, several mayors from oppositional parties hoisted rainbow flags in front their offices as a sign of Pride support, but these were subsequently taken down by the Mi Hazánk (Our Homeland) party’s Vice President Előd Novák and a group of Ferencváros club soccer ultras (known as fradistas). Not only did Fidesz opinion leaders not distance themselves from the events, they later made a celebrity out of Novák. The ruling party’s politicians didn’t go this far (although it is telling that László Kövér described Karácsony’s gesture as scandalous), nevertheless, on a symbolic level an initiative originally launched in 2011 has entered the public sphere as a kind of counter-flag operation: Fruzsina Skrabski, founder of the Three Princes, Three Princesses Movement (a Hungarian civil organization promoting childbearing and the traditional family model), encouraged municipalities to put the foundation’s ‘baby flag’ on display. „Originally, the flag would be put on display whenever a child was born, but now we are encouraging everyone who agrees with our goals to put one out,” Skrabski requested, effectively using a symbol expressing the joy of childbirth to challenge the ideas expressed by Pride. A number of Fidesz mayors immediately joined her initiative, and later even Gergely Karácsony promised to put out the baby flag in September – despite the homophobic association, it likely would have been relatively unpleasant from a political point of view to be forced into the role of „the oppositional mayor of Budapest who is indifferent to the birth of Hungarian babies.”

Then in the fall came the scandal surrounding the children’s book Meseország mindenkié (A Fairy Tale for Everyone), which featured main characters from minority and disadvantaged groups (including LGBTQ).

The Mi Hazánk party deputy leader Dóra Dúró shredded a copy of the book since her party considers it an attack on Hungarian culture and homosexual propoganda aimed at children. The tsunami of opinions and counter-opinions that followed was of an intensity rarely seen, even for this subject matter. A signature collection was launched against the book on the right-wing Christian petition platform CitizenGo (the petition’s creator claims to have received death threats as a result; at the time of this article’s writing the campaign had gathered nearly 90,000 signatures). Those in support of the book, on the other hand, began to order copies for themselves, and as a result the publisher promised to reprint thousands by October.

Emőke Bagdy, a psychologist known for her conservative views, explained that the storybook could trigger a crisis within children, to which a thousand of her colleagues responded by signing a petition expressing that they didn’t consider the book dangerous. As a counter-response, yet another petition was launched, this time in support of Emőke Bagdy. Human rights activists organized a public reading of some of the book’s tales, however even its online format faced difficulties due to extreme right-wing protesters yelling on the street outside the establishment. The mayor of Csepel (a district of Budapest) banned the book from local preschools. At a government press conference Gergely Gulyás, the Prime Minister’s chief of staff, spoke about the „dangers posed to children” by the book.

Propaganda operations are well underway, but even Orbán has spoken up

Meanwhile, not only has there been a growing number of such events, the topic of gender and LGBTQI has also received a lot of attention in public discourse and right-wing publicity. Even back in his memorandum regarding the need to revamp the European People’s Party, Viktor Orbán had already set the issue side by side with that of migration: „We gave up the family model based on the matrimony of one woman and one man, and fell into the arms of gender ideology. Instead of supporting the birth of children, we see mass migration as the solution to our demographic problem,” he wrote.

He again brought up the issue in an essay dedicated to the start of the fall political season: „Schools should protect the ideal and values of the family and should keep minors away from gender ideology and rainbow propaganda.” In an interview, the Prime Minister commented on the commotion surrounding the children’s storybook: Hungary is tolerant and patient with homosexuals, but „there is a red line – leave our children alone.”

And that is just the stigmatization of the issue at the highest level of government. Besides this, there is also the propagandistic press and the domain of countless satellite organizations associated with Fidesz. At Origo, Pesti Srácok, 888, and the public media outlet Híradó.hu and its peers,

the topic of gender and LGBTQI is frequently portrayed in a negative light. A keyword search attests to the fact that such articles have become more common in recent months.

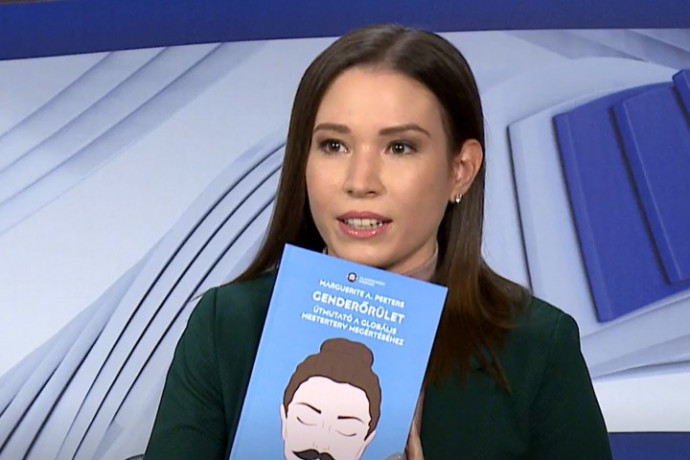

The Center for Fundamental Rights, an organization disguised as an NGO but is in fact financially supported by Fidesz funds, regularly takes a stand on the matter. Moreover, they recently published The Gender Revolution, which they earlier had announced as the counter-book to A Fairy Tale for Everyone. As expected, they received press support from public television.

This pattern of events can be further extended, but perhaps the main idea is already apparent from this: the idea of „gender ideology” is currently making its rounds among Hungarian right-wing groups, and it is slowly approaching the same level of demonization that migration has reached. But why are the groups that fight for gender equality or for the rights of sexual minorities such popular targets? It is by no means just a trend affecting Hungary. It is comparable to the stigmatized issue of migration in that its political beneficiaries seek to paint a picture of a culture war taking place between certain minority groups and the „average, normal” majority – and based on their record, they’ve been quite successful.

The right’s effective execution of a left-wing strategy

In the West, the root of the whole conflict dates back to the late 1960s, when liberals and those on the left began to realize that when it came to the pursuit of the great common goals (freedom, equality), the stakes were different for different people. The everyday problems faced by those of various ethnic, sexual, and other minorities are often completely different from those faced by society’s majority (even if they can be grouped into the same political camp from a macro perspective). So the problems encountered by a female, gay, or black worker aren’t identical to those of a white, male worker, not even if they happen to work in the same factory. As a result, there’s value in taking into consideration the distinctions between the disadvantages of various origins and giving a voice to minority experiences. This gradually led to a shift in focus from the greatest common denominator to particular group interests and identities. The dominant social movements of the following decades were no longer based on wealth or class (as was customary in classical left-wing politics) but rather on culture and identity.

Minorities were no longer (or at least not only) demanding equal rights, but also recognition and respect for their diversity, especially since it became clear that the theoretical institutionalization of various social and civil liberties could not eliminate their disadvantage in practice.

The triumphant procession of identity politics was underlined by the fact that traditional left-wing parties were losing their footing by the 1980s: social developments and a phenomenon known as the Neoliberal Turn was slowly destroying the classical framework of class politics, welfare state institutions began to deteriorate, trade unions were becoming less and less influential, and the Soviet Union had weakened and finally collapsed. In pursuit of new objectives and electoral base, the parties made a logical shift compatible with basic left-wing principles to endorse minority rights in a more prominent manner.

But many argue that this shift in identity politics ultimately led to the left losing touch with the working class, i.e. their traditional base, or the much more fragmented group that takes its place today. (It might be noted that the extent to which the rise of identity politics is to blame for the failure of left-wing politics or the deterioration of democracy is still intensely debated in academia and the public sphere;although manyinfluential thinkers support this idea,there is an interpretation that actually all politics is identity politics, so there’s no use passing the buck to it and abandoning marginalized groups.)

In the meantime, the populist right came up with a good idea of how it can take advantage of this political reset and has been making use of identity politics much more effectively lately than the left or liberals.

The gist of their technique is to exhaust the toolbox of the original movements of identity politics in order to come up with a message, which is then used to engage the social groups that they feel lack representation. This is what led to the creation of some successful political identities, which, when you stop to think about them, are actually quite bizarre: the white population turned minority in their own country, the young people professing traditional family values who will soon need to feel ashamed for their heterosexuality, and the men who can no longer pursue romantic interests for fear of being labelled a chauvinistic predator/rapist. As for those marked as enemies, we find such exaggerated stereotypes as liberals who wish for an Islamic caliphate in Europe, adolescents who begin to feel attracted to the same sex as the result of all the sensitization measures, or gender activists whose reaction to a little boy playing dress-up in a skirt is to snatch him up and snip off his willie.

The right-wing identity politics emphasizing Christian, national, white pride – whose roots date back to the Identitarian movement in France in the 1960s – reinforces and ultimately forms a strong group identity out of such fears whose seeds are present in many people but without deliberate stimulation, wouldn’t necessarily spring up with such intensity. Psychological research has demonstrated that while many people have a predisposition to be intolerant of any kind of otherness, for this to manifest itself in practice (especially so that it becomes a strong sense of identity) requires external stimulation.

„It’s as though some people have a button on their foreheads, and when the button is pushed, they suddenly become intensely focused on defending their in-group … But when they perceive no such threat, their behavior is not unusually intolerant. So the key is to understand what pushes that button,” a psychologist researching the phenomenontold the Guardian.

The strategy has paid off in Poland

When it comes to who’s pressing the matter, it can hardly be a question these days in countries where politics based on fear tactics against various minorities has been proliferating at a perceptible rate. Whether it’s Donald Trump or the Brexit campaign, there are many examples of right-wing populist politicians exacerbating social tensions for the sake of votes, but let’s stay close to home and take a look at Poland, where gender and LGBTQ was the hot topic of the recent election, something that the government has been relishing since its victory.

Poland is considered to be particularly religious in comparison with the rest of Europe: Catholics make up over 90 percent of its population. According to church statistics, more than a third of them actively practice their faith and attend church on Sundays. With such demographics, it is obvious why Poland is not a stronghold for contemporary feminism, homosexuality or transgenderism. But what has been happening in the country on this front in recent years is extreme for Europe. The situation there, which is slowly degenerating into aculture war, is of particular interest to Hungarians because some rather strong parallels are beginning to appear between the two countries.

According to reports by local human rights organizations, the quality of life of sexual minorities has been deteriorating in Poland ever since the right-wing populist, openly homophobic Law and Justice party (PiS) came to power in 2015.

In recent years, municipalities encompassing about one third of the country have adopted resolutions symbolically declaring themselves „LGBT-free zones”,

which by no means provides gay people living there with a sense of security. The government also continues to bring up from time to time the issue of further tightening one of the toughest abortion laws in Europe (although mass demonstrations have been successful thus far in beating it back). The 2019 elections saw the anti-gender, anti-LGBTQ enthusiasm shift into a higher gear:

Some analyses indicate that PiStried to compensate for its loss of popularity due to corruption scandals by honing in on homosexuals and those representing „gender ideology”.

It was in this context that the ruling party condemned an opposition-led sex education program in Warsaw that included a discussion of sexual orientation with students (which is in line with WHO standards for that matter). Although the extent to which this rhetoric played a role is not known, PiS ended up winning the election in 2019, and Poland’s government and its president have since been actively expressing their views whenever possible. For example, President Andrzej Duda recently publicly called „LGBT ideology” „worse than communism” and something that „children must be protected from.”

This past spring, the Polish Parliament was presented with a bill that would ban sex education in schools and equate homosexuality with pedophilia (it was ultimately not voted on but passed on to a parliamentary committee for further elaboration). In the summer, Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro proposed that Polandwithdraw from the Istanbul Convention on combating domestic violence because he considers it to be harmful and simply spreading gender ideology under the pretext of protecting women. On top of all that, the matter of toughening abortion lawscame up again in the fall.

Is Fidesz testing the waters?

Similar declarations may become more and more commonplace with Hungarian politicians too. While the majority of the truly harsh forms of expression (taking down flags, shredding books) may still be linked to the overtly far-right Mi Hazánk party, it seems that

leading Fidesz politicians are also venturing more and more boldly and frequently into the openly homophobic camp that considers the concept of gender as dangerous.

It is enough to recall such events as House Speaker László Kövér’s comparison between same-sex couples wanting to adopt and pedophiles, Head of the Prime Minister’s Office Gergely Gulyás’s statement regarding the „endangerment of minors,” or Viktor Orbán’s declaration that „they should leave our children alone.”

Furthermore, one might question the political independence of Mi Hazánk considering that Fidesz often helps the party in a particularly visible manner to keep its topics on the agenda, and we may now be seeing this strategy in action with anti-gay legislation. The book-shredding Dóra Dúró was even invited to a venue that often hosts public events for Fidesz’s media outlets, the Polgári Mulató, for a talk with a state news presenter and the creator of a CitizenGO petition to ban the book A Fairy Tale for Everyone.

It’s also worth noting that the book shredding and the gig that accompanied it by no means mark the end of the Mi Hazánk party’s activities: party leader László Toroczkai recently announced that a national campaign would be launched „against LGBTQI-etc propaganda”. Dúró, meanwhile, called on parliamentary leaders to support her proposed resolution to „ban homosexual propoganda in schools”. We had asked Máté Kocsis and István Simicskó (the parliamentary leaders of Fidesz and KDNP) how they would respond to this, but we still had not received a response by the time the original article had been published.

Something else that reveals the efforts to probe the topic is the survey that was conducted by the pro-government Századvég Foundation utilizing the children’s book scandal. They concluded that „most Hungarians believe that LGBTQ sensitization is not appropriate in preschools or primary schools.” The results of the survey received coverage across all right-wing media outlets. Similar to Poland, Hungary’s „anti-gender” discourse places a lot of emphasis on the protest against the „brainwashing” of children, which is no coincidence: fear-based group identity tactics can be much more successful by creating the sense that the most vulnerable are at risk. The change of tone, the more frequent remarks, the experimentation with the issue, and its constant reference in the media give away the fact that the government is trying to see whether the Polish strategy could work in Hungary.

A warning sign: the increasingly hostile rhetoric

We asked Tamás Dombos, board member of the Háttér Society (one of the oldest and largest LGBTQI NGOs in Hungary), about the growing anti-gay atmosphere and how they view the development of Hungary’s situation. According to Dombos, the government’s recent homophobic statements are not so out of line with the current trends, as the government’s position on the issue, evidenced by the occasional newspaper headline, has been consistently dismissive since 2010.

The only thing that changed last year was that discourse became more hostile: the administration didn’t attempt to distance itself from László Kövér’s comparison with pedophiles.

The only comment at the government’s press briefing was that every child has the right to a father and a mother. According to Dombos, it’s not so much in the legislative measures – like last year’s anti-transgender law or steps toward banning same-sex adoption – where this intensification can be seen. The history of those measures stretches back years and is filled with bureaucratic battles. They don’t fit into the familiar political scapegoating pattern whereby the government picks out an issue, stirs up the political discourse surrounding it, and finally offers a simple solution, such as it did with the issue of migration.

Dombos believes that the reason for the transgender law coming out this past spring, for example, might have more to do with the fact that after authorities had suspended the processing of gender change applications on multiple occasions for long periods of time – officially because they were waiting for a new piece of legislation – many people were suing the state and winning their cases. As such, some action had to be taken. However, the government, with its Christian-Conservative values, wasn’t about to pass a law codifying transgender rights, so instead, it opted to make gender change legally impossible. Amendments to the adoption laws were on the agenda even four years ago, after the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights had established that public authorities had acted in a discriminatory manner when they prevented a woman living in a lesbian relationship from adopting.

For the Háttér Society, it is rather in the more hostile words that they perceive a change: previously, leaders of the ruling party would barely comment on LGBTQI matters, and even then, it would be only in response to a direct question and much more reserved. Viktor Orbán is always sure to position himself between the two extremes – it’s important to him that there’s always someone standing further to the right than him on the issue. But the extreme statements of the far-right have extended this middleground, leaving more room for the Fidesz party to slide further to the right, Dombos said. At the same time, he believes it would be premature to say whether this is a long-term political strategy similar to the migration discussion, and it is up in the air whether this topic will remain on the agenda in the coming months and years.

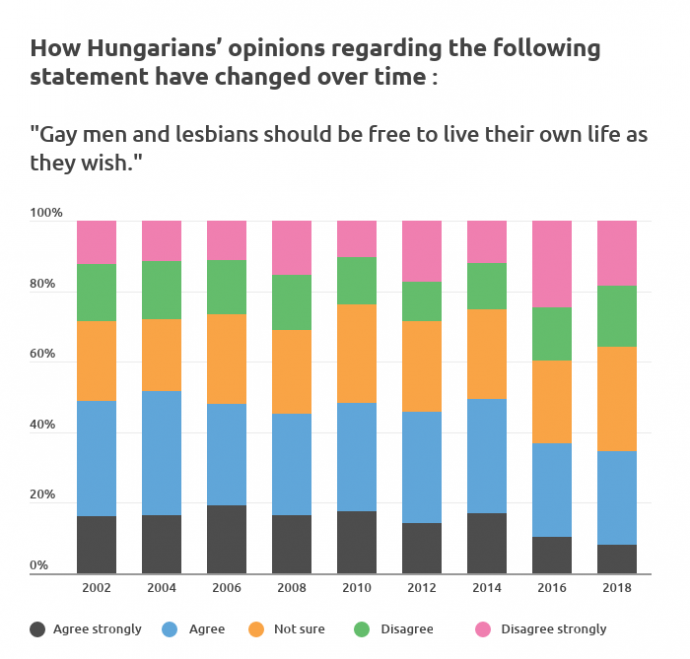

Tamás Dombos also mentioned that the domestic acceptance of LGBTQI individuals started to deteriorate long before the current push to incite the public.

The latest data from the European Social Survey and Eurobarometer surveys also shows a shift in attitudes after 2015: although the situation had been slowly improving and a growing acceptance could be seen, the 2016 data shows a significant decline. According to their analysis, this may be related to the fact that the campaigns against the various minority groups (migrants, Roma, homeless) not only increase intolerance towards the given minority, but also a more general intolerance in society.

It is worth noting that with the backsliding of recent years, Hungary has ended up in the bottom quarter of EU countries in terms of tolerance towards virtually all sexual minorities. If the current trend in discourse continues and the topic continues to be treated in a tone similar to the present one until 2022, the situation could further worsen.

But what is gender ideology?

As a matter of fact, there is no such thing as a unified „gender ideology” – this concept was coined by right-wing populists as a label for groups with whom they don’t see eye to eye regarding matters involving sexual orientations, gender identities, and gender roles. The word ‘gender’ is generally translated in Hungarian as ‘társadalmi nem’ (lit. social gender), and the concept has nothing to do with the denial of biological gender. Gender researchers start from the idea that the biological differences between men and women alone do not explain their place in society. These differences are not what bring about gender inequalities, but rather the fact that communities determine what forms of behavior are considered feminine or masculine.

The way individuals grow up is that they act, socialize, and acquire the roles associated with their gender all within this system of norms which is perceived to be natural. As largely social constructs, however, even these roles can undergo changes. For example, it is thanks to such changes that women can now vote, attend university, etc. Moreover, the „gender ideology” label tends to be used to lump together groups having completely different worldviews, striving for different goals, and in some cases, maintaining strongly opposing perspectives. If someone is a feminist or supports gay rights, it is by no means certain that they support transgender rights as well. Recently, for example, passionate women’s rights activist J.K. Rowling made statements about transgender people that cause quite a stir internationally.