Tracing the bomb threats in Hungarian schools: all of Europe is targeted, generating panic and testing among likely goals

- The series of mass school bomb threats, which reached Hungary in January are part of a coordinated operation that has been ongoing since last spring.

- Most of the countries targeted last year and this year are NATO member states, with some having been targeted more than once.

- In addition to generating panic and confusion, the likely purpose of the operation might be the testing of a country's administrative systems.

- The Islamist threat is just a cover.

- There may be a state actor behind it all, applying hybrid warfare.

- Both Russian and Ukrainian traces can be identified in the operations, but Moscow is the only one with a strong motive.

23 January will be a memorable date in Hungary. There was no mass disaster, no natural calamity, no violent crime that shook the whole country, yet the lives of many were disrupted when students were evacuated from their schools all over the country due to a mass bomb threat. According to police data, 292 educational institutions received threatening emails in a single day, which indirectly transformed the day for thousands of people.

After evacuating and searching the schools, the students had to be accommodated. State and local government institutions took on extra tasks, parents had to rush away from work, which meant that companies had to scramble to replace them for the day. In the end, no bombs were found in any of the schools, the threat was a false alarm.

Political actors commented on the events in line with their own interests. Some of the opposition blamed the state and the government, while the pro-government press mainly focused on amplifying the narrative of the threat posed by migration and Islamists, attempting to illustrate the dangers facing Europe.

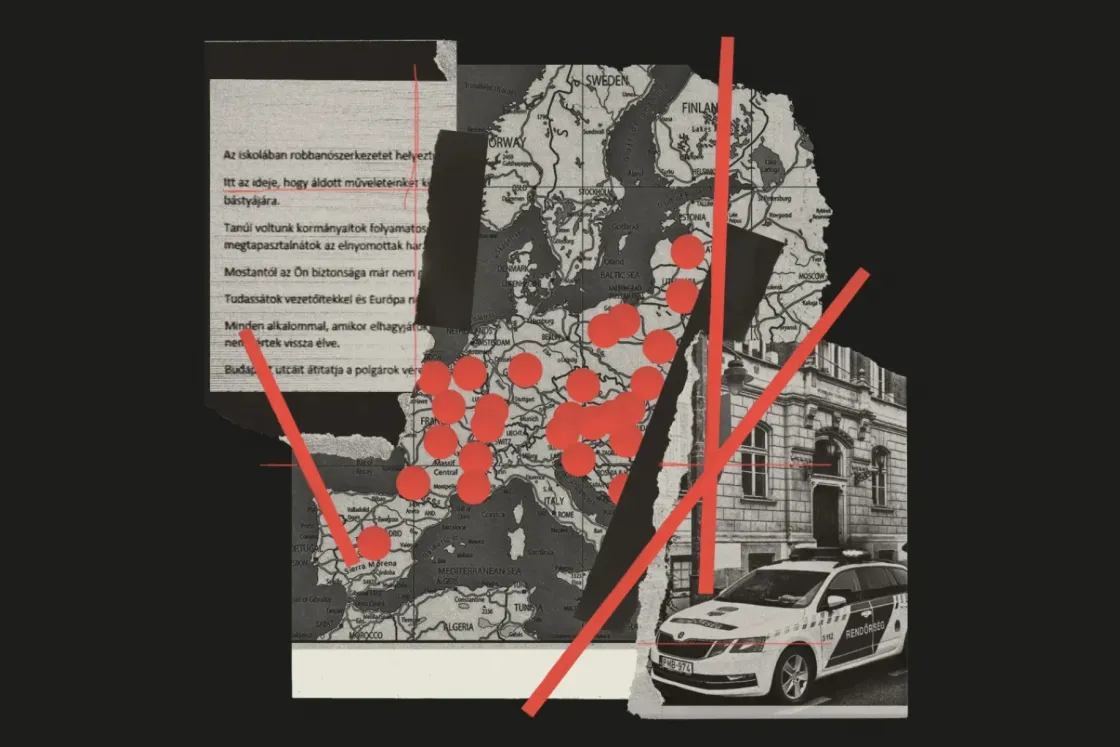

Although the previous reports had said that this type of threat was primarily affecting the Central and Eastern European region (Bulgaria, Slovakia and the Czech Republic were mentioned in addition to Hungary), the data collected by us indicate that the situation is more serious. Telex's research from open sources makes it clear:

the perpetrators are targeting the entire continent, the operation has been in full swing for several months and for now, there is no sign of it stopping.

The operation, which appears to be coordinated and is designed to create panic and confusion has been ongoing since last spring – with the exception of the summer period – targeting schools and other institutions across Europe. Apart from schools, the most frequent targets are courts, prosecutors' offices and shopping centres. A side effect of the operation is the emergence of followers who copy the method or are inspired to carry out similar threats, but are amateurs.

There are some common elements in the bomb threats against schools:

- with a few exceptions, the perpetrators are professionals;

- the content of the letters is always fabricated, it only pretends to be a jihadist operation;

- no bombs have been planted at any of the locations; nevertheless

- all of the threats are being taken seriously by the authorities.

Whoever planned this operation was well aware that if schools were threatened, the authorities would have to act. This is true even if, based on the letters, security experts consider the threat to be unfounded. And this is precisely why this operation causes damage even if it does not result in human casualties: it costs the state money, ties up human resources and, because it affects families, it can have a direct impact on a wide range of people: a single operation can directly affect tens of thousands of lives.

Based on our research, it seems certain that, apart from a test period, the recent mass bomb threat in Hungary was the latest in a series of operations launched in the spring of 2024 – although attacks of this kind or of a similar nature already hit some European states in 2022 and 2023.

On 5 March last year, due to a threatening email, police evacuated several primary and secondary schools in Bratislava, Slovakia. According to press reports, the letter said that bombs had been planted in several schools and in trucks. Whoever wrote the letter phrased it as a jihadist threat, referring to "enemies of Allah". The email also evoked the 2016 terrorist attack in Nice, when a man drove a truck into a crowd, killing 86 people and injuring more than 400 others. Although grammatically correct, the email’s sentence structure was found to be unusual.

Our research shows that in addition to the Eastern European and Baltic states, Spain, France, Germany, Austria, Cyprus and Greece were also among the targets of this operation, which has been ongoing since spring 2024. We collected all the cases that have been made public. By examining them, it becomes evident that some of the waves affected several countries within a short period of time, all of which – with the exception of Cyprus and Austria – are NATO member states. The following are several examples of some of the more intense periods last year, with the specific date of the attack marked in brackets for each month:

- March and early April: Slovakia (5th), Belgium (8th), France (20th-27th), Bulgaria (28th – 2nd April)

- May: Slovakia (7th), Cyprus (17th), France (23rd), Greece (29th)

- October: Austria (1st and 6th), Greece (17th), Poland (21st)

- End of November and December: Germany (25th), Austria (27th), Poland (11th and 13th), Spain (18th)

Our analysis also shows that some countries were targeted by the perpetrators more than once: the most striking examples for this are France and Poland, as well as Austria, Bulgaria and Greece.

It cannot be ruled out that the January attack was not the first time Hungary was attacked. Although on a smaller scale, a similar incident occurred in May last year, affecting at least seven schools. It was reported by Magyar Hang at the time, the police confirmed the news, and although it was covered by some media outlets, the incident did not receive much publicity. But whether the same perpetrators were behind the May and January incidents remains unknown.

In any case, having analysed the pattern of attacks and having seen the above examples, it is not at all impossible that what we saw in Hungary on 23 January could happen again, as the pattern observed in Europe clearly implies that repeated attacks do happen.

The first French wave with videos of beheadings

Although the first operation targeted Slovakia at the beginning of March last year, the biggest attack during that period was carried out against French educational institutions. Several French schools – mainly high schools – received terror threats in March 2024. On 20 March, students in at least 40 French schools received threatening messages via the educational platform Espaces Numériques de Travail (ENT). The authors of the messages claimed to be acting on behalf of the Islamic State and threatened to carry out bomb attacks the following day. The threat was found to be false and presumably not related to the Islamic State.

A day later, fifty schools in the Île-de-France region received similar threats. These were accompanied by videos of beheadings. Six days later, several high schools and primary schools in Paris also received messages claiming that there were bombs in their buildings. Bomb squads were deployed to secure the sites, but no explosive devices were found.

In response to the threats, the French Ministry of Education suspended the messaging function on ENT platforms until the spring break, citing security concerns. Several suspects were arrested in the course of the investigation, including a 17-year-old boy suspected of carrying out one of the false threats. This latter case could be significant because, as can be seen, whoever is behind the attacks is obviously counting on finding followers who will copy the method. Only, the amateurs are more likely to be caught than the professionals working with state backing. The fact that a large number of the mass threats directed at schools are carried out by professionals is confirmed by the fact that the few perpetrators who are caught are usually young schoolchildren or simple pranksters.

The exact email addresses of the senders of the bomb threats in France have not been released by the authorities. However, they did reveal that more than 150 educational institutions were targeted in March alone. The French had some previous experience as they were hit by a wave of cyber-attacks in 2023, but at that time the threats were directed against airports and museums.

Not to be neglected is the fact that a year before the wave of school bombings in France, between 28 and 30 March 2023, dozens of schools and universities in Bulgaria received bomb threats (they were all located in the towns of Sofia, Plevna, Sliven, Varna and Burgas). The threats were made via email and phone, and all the buildings had to be evacuated.

The first Bulgarian incident is noteworthy because the perpetrators acted just days before the parliamentary elections.

The email addresses used to make the first bomb threats in Bulgaria were registered in the UK and the US. Despite this, the Bulgarian authorities suspected that they were dealing with a form of hybrid warfare that was somehow linked to Russia. Hybrid warfare involves the aggressor using overt, covert military, paramilitary and even non-military means and procedures. The bomb threat is a good method of inflicting damage because carrying it out is inexpensive.

In any case, this Bulgarian threat was the first time when the Russian connection officially and publicly came up during the investigation, although this was still well before the major European wave that began in spring 2024 and has been going on ever since.

The second French wave

The French attacks of March last year were followed by others on 16 April, when five secondary schools in Mulhouse and Riedisheim received false bomb threats. Then, on 23 May, more schools had to be evacuated and entire streets were closed off in France. In April, there was also a school bomb scare in Denmark, but only one school was involved and a young person was arrested, so the Danish case needs to be kept separate.

After the second wave in France, Slovakia was targeted again on 7 May and was thoroughly saturated: in the May operation, the authorities recorded a total of 995 bomb threats. In addition, there were 110 bomb threats against banks and 40 against shops selling electronic equipment. By this point, the police were investigating the threats as a terrorist act.

Ten days later, on 17 May, Cyprus and Serbia were hit. The Russian connection reemerged again at this time, since the threats in Cyprus had been found to have come from a Russian domain. In Serbia, 78 primary and 37 secondary schools received bomb threats and the affected sites were all evacuated. The psychological impact of the Serbian threat was further amplified by the shock of a school shooting which had taken place just a few days beforehand.

On 29 May, the attackers targeted Greece, with security services registering at least 200 reports. Once again, the author of the letter claimed to be acting on behalf of the Islamic State, but in this case too, the Greek authorities found traces of Russian involvement: the threatening letters were sent via a Russian webmail provider, but the email account was opened via a US-based VPN provider. According to Greek investigators, the perpetrators' goal was to create panic.

The Baltic countries did not panic

The Greek incident was followed by a long break as schools closed for the summer. But once classes started again in September, the operation in Europe also resumed. This time the Baltic states, Latvia and Lithuania were the ones targeted. Schools in all Latvian districts received emails with bomb threats.

The Baltic countries had a very different approach to the threats than the rest of Europe. Schools were advised not to suspend classes and to simply consult the relevant authorities rather than alert them. The police also requested that schools avoid "unnecessary evacuations" and only notify the authorities if they find a suspicious object on their premises.

The Baltic countries' different response to the threat is understandable, as Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia had already been hit by a wave of cyber attacks in the autumn of 2023. The Latvian police classified the bomb threats as low-risk threats, but recognised that the purpose of the attacks was to create fear and prevent public institutions from functioning properly.

The security services of the Baltic States clearly viewed the threats as an operation conducted by a hostile state, designed to create panic. At the same time, the Lithuanian authorities also concluded that the attacks were coordinated. Although it was not suggested that they suspected the Russians behind the attack, the Baltic States definitely regard Russia as a hostile state.

Almost at the same time as the threats against Latvian and Lithuanian institutions, schools in the Czech Republic and – for the umpteenth time – Slovakia were targeted with bomb threats as well. In the Czech Republic, 600 primary schools were threatened with bombs on 3 September and a further 400 schools, including high schools, the following day. The two threats were not sent from the same email address, but police said there was evidence of a link between the accounts.

The Czech secret service believes that Russia was behind the bomb threats. "There are cyberspace operations which are interlinked with direct attacks against institutions in our country, [...] such were for example, the threatening emails about planted explosives in September, which targeted several schools in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and which had clearly visible traces of Russian involvement," Michal Koudelka, the head of the Czech secret service said later on. "We are witnessing a kind of globalisation of evil, where the countries of the axis of evil – Russia, China, Iran and North Korea – support, complement and help each other to achieve their goals. We are therefore witnessing a phenomenon that is both serious and dangerous," said Koudelka.

Meanwhile, the number of bomb threats also increased in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s capital, Sarajevo: the airport, high schools and shopping centres were among those receiving threatening messages.

Austria was next in early October. Although at first it was not schools but the main railway stations in Linz and Klagenfurt that had to be evacuated because of a bomb threat, the letter included the words "Allah Akbar". On 6 October, however, a school in Linz had to be evacuated for a similar reason. Greece was targeted again on 17 October. A hospital, a courthouse and a metro station were threatened and all had to be evacuated.

Poland came next in a series of waves in October, November and December. On 21 October, several prosecutor's offices and schools in Wrocław and Lower Silesia were threatened, and on 4 November, public and private educational institutions received threats. In Warsaw alone, dozens of schools received a threatening email.

Towards the end of the year we also found a case outside of Europe. On 25 November, the FBI issued a statement announcing that bomb threats had been made against polling stations in several US states. Here too, the false threats were sent from a Russian email address.

On the same day, Germany experienced what many European countries had already seen. Educational institutions in a total of seven German federal states received threats. Among the cities affected were Hannover, Erfurt and Leipzig, as well as the municipality of Stuhr near Bremen. The threats led to the suspension of classes in some places (e.g. Stuhr), while in others (e.g. Erfurt and Hannover) the authorities found no grounds for the threats and classes continued without interruption. German investigators also concluded that this was a coordinated operation.

Two days later, it was Austria's turn to be targeted again, with several educational institutions in Vienna receiving threats.

In December, it was Poland’s turn again. On 11 and 13 December, Polish schools, including both secondary schools and higher education institutions, were threatened. Institutions reacted to the threat in different ways, some evacuating students, others ignoring the threat, similarly to how it was done in the Baltic States and some German examples.

On 17 December, it was back to Austrian schools again, followed a day later by Spain, which had not been affected until that point: there, various private schools in half a dozen provinces received threatening messages. The Spanish police issued a statement "urging the public to calm down" and called the incidents a "malicious nationwide email campaign". Once again, there was no question about the institutions concerned being the victims of a coordinated operation.

The operation didn't stop in 2025 either. First, France was targeted again, with several French schools evacuated on 13 January. Then it was Bulgaria again, where they had already carried out an operation in the spring of 2023. One day later, on 23 January, Hungary was targeted, followed by Slovenia four days later, and then, only two days after that, Slovakia was attacked again.

At the time of the Bulgarian institutions being threatened, and a day before the Hungarian bomb threats, a report was published in the Russian press, implicating Ukraine: on 22 January, a Russian press report claimed that Ukrainian scammers had started buying Russian schoolchildren's email accounts for 7-10 dollars and using them to send fake bomb threat messages. According to the Russian report, the criminals started using this method after Russian mobile phone operators made it mandatory for SIM card holders to be identified.

The Balkans had been hit by a wave two years earlier

It is quite conceivable that the perpetrators may have tested the method used to send bomb threats to multiple schools at the same time around 2021 and 2022 in the Balkans: in December 2022, there were such occurrences in Kosovo, Serbia and Croatia too.

The Russian connection also came up in the Balkan wave, albeit in a different context than in the later instances. The wave of fake bomb threats in Serbia began on 11 March 2022. It was then that Air Serbia flights to Moscow received threats. At that time, these were the only flights to Russia from Europe. Over the next three weeks, dozens of fake bomb threats were reported on flights to and from Moscow.

In April that year, fake bomb threats were sent to the email addresses of several shopping centres in Belgrade and Niš. Later that month, 23 secondary schools received group emails with bomb threats. On 11 May, two student dormitories in Belgrade were threatened, followed by 97 elementary schools and some high schools, as well as some shopping centres and bridges in the capital a few days later.

In these cases, with assistance from Europol and Interpol, the Serbian Ministry of Interior requested data from Swedish, Lithuanian, Swiss, Russian and Hungarian state bodies, as well as from Google, but there is no information on whether the requests were successful. The fact that they requested data from the Hungarian authorities as well, implies that the perpetrators may have used Hungarian digital infrastructure to carry out the operation.

Ana Brnabić, the Serbian Prime Minister at the time said that the reports of bombs being planted in Serbia constituted external pressure. Brnabić claimed that Serbia received these threats because the Serbs did not impose sanctions against Russia after it launched the war in Ukraine. This interpretation is completely contradictory to later opinions. Indeed, if Brnabić's view is to be accepted as truthful, then the threats to Serbia should be attributed to an actor opposed to Russia.

Montenegro also faced false bomb threats in the spring of 2022. In late April, some schools and municipal buildings were evacuated in response to anonymous bomb threats. More than 40 schools in the capital Podgorica and across the country had to be closed.

Do all roads lead to Moscow?

It is obvious from last year's incidents that, although the threats appear to be Islamist, it is not jihadists who are behind them.

If the perpetrators were indeed jihadists, then the relevant European security services, with the assistance of partner organisations in the Middle East, such as those in Israel, would have detected it by now, or else the Islamist organisations involved would have claimed responsibility. This implies that the jihadist text is merely used as a cover story by the perpetrators.

Given the professionalism of the execution, one theoretically could not rule out the possibility that it was the work of a hacker group or an organised criminal group. However, this is contradicted by the fact that no financial gain can be expected even from such a coordinated operation. There is no money involved, unlike in the case of a blackmail operation, so it would be difficult to find a motive. For example, in India, in December 2024, 40 schools were evacuated because of a bomb threat, but in that case the perpetrators wanted money. And when the Hungarian Defence Procurement Agency was recently attacked by hackers, the perpetrators were also looking to make a profit. Therefore, it is most likely that the bomb threats were made by a hostile state, even if the work may have been outsourced to one or more external non-state actors, i.e. hackers.

How would this benefit Ukraine?

As in other attacked countries, the technical trail from the attacks in Hungary has been shown to lead to a Russian email provider via a Ukrainian IP address – but this still does not prove the involvement of the Russian or even the Ukrainian state. However, it is worth looking at which of the two countries would have greater interest in carrying out such an operation aimed at weakening the predominantly NATO and EU member states.

Ukraine's motive could be to shift suspicion onto Russia based on clear Russian clues, so that public opinion would blame Moscow for the inconvenience. However, this theory is quite weak: commentaries on Russian involvement only reach a small minority of news consumers at most, and the public willingly or unwittingly gets stuck with the image of the jihadist threat, especially if some media outlets adopt the narrative of the Islamist threat without criticism.

Burdening the administrations of its European allies is also not in Ukraine's interest. Moreover, the Ukrainians would stand to lose a great deal if it were proven that they had anything to do with these operations.

Not so the Russians, who are known to regularly use hybrid warfare against Europe. Hybrid attacks from Russia have increased sharply in the last year or two, the increase in their number coinciding with the time the bomb threat campaigns started, with 44 reported in 2024 and only 13 documented in 2023. The attacks included the burning of a shopping centre in Warsaw, the assassination of a Russian deserter and the manipulation of elections in Romania. The geographical scope of Russian interference has also been growing: it no longer affects only Scandinavia and the Baltic States, but also France and Germany. The bomb threats operation would fit in perfectly with this strategy.

How would this benefit Russia?

When it comes to Russia, one could list the reasons why its involvement in something like this makes sense almost endlessly. It is in Moscow's interest to destabilise the EU, to intimidate its population, to create panic, to create confusion, because – although not the way it is with Ukraine, but – Russia is at war with Europe.

Unlike Ukraine, overwhelming the European security services is in Russia's interest, especially since the Russian-Ukrainian war broke out in February 2022. In 2022, European secret services mobilised considerable forces to counter the Russian threat, because it is real: cyber attacks are a regular occurrence, as in the case of the Russian hacker attack on the Hungarian foreign ministry.

Investigations into bomb threats are guaranteed to overwhelm the country's counter-intelligence, because there is no authority that can simply turn a blind eye to something like that. While there is little chance that they can get to the bottom of these operations, it takes a considerable amount of resources away from the system. While the services are searching for the perpetrators behind the bomb threat, they have less energy and manpower for other, equally important matters.

The Russian connection is further supported by the fact that the operation launched in spring 2024 appears to have been tested in the Balkans years earlier, before 2023, when the first major wave reached the Baltic states, which are less friendly to Russia. Russia is particularly well-positioned in the Balkans, and active intelligence measures of this kind tend to be tested, preferably in a more ideal, safer, but still foreign environment.

This is not a theory, since during the Cold War the KGB also used to do test runs of these types of active measures, and the modus operandi has not changed since then.

A first-hand experience of hybrid warfare

Bomb threats against schools have a direct impact on people and families, which sets them apart from hacker attacks on state administration, which the public does not know about, since those are usually kept secret, former counter-intelligence officer Ferenc Katrein told Telex. This is why they are effective, at least in the sense that they can create panic and instill fear and personally affect a large number of people.

But Katrein says it may be just as important that regardless of which state is behind these operations, it is an effective way to test how the targets react to such an event. The reactions can then provide valuable information. Such an operation can for example reveal the decision-making mechanism, the key decision-makers, the speed of their reaction, as well as what human and technical resources they have at their disposal. This is all information that becomes visible in such a high-pressure situation.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!