My whole life has been about proving that even as a Romani, I can achieve as much as a white person

"I grew up without ever being loved. Ever since I was a child I planned on becoming an athlete because then people would accept me and love me," says Melinda Zsiga, a two-time world bronze medallist kickboxer who for a long time preferred to pass herself off as Yemeni so as not to have to struggle the prejudices against Romanies. As part of a joint series by Telex and the Equalizer Foundation, she wrote an opinion piece on the career prospects of a Romani woman from foster care.

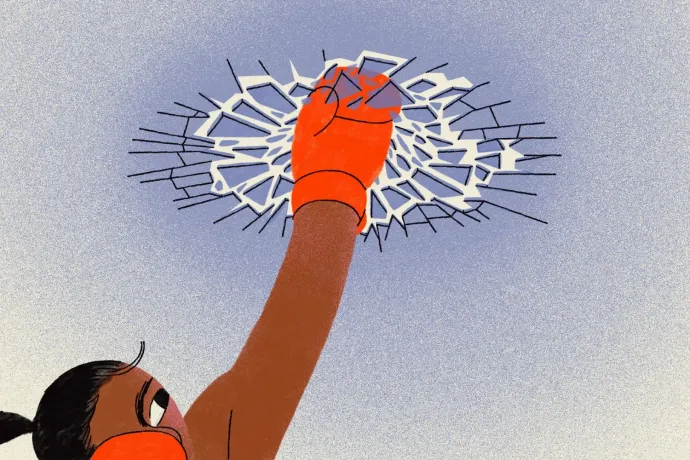

When it comes to the careers of Romani women, the issue is not yet about breaking the glass ceiling, but simply about being able to compete at all – perhaps this sums up what I think is the most important aspect of the matter. However, my aim is not to make hard and fast statements about the situation faced by women or the Romani people in the labor market but to tell my own story. I think it's a good example of what it's like to succeed in Hungary today as a Romani who had grown up in foster care.

All my life I had planned on becoming an athlete – then people would love me. I grew up without ever being loved, at least that's the way I experienced it. I was passed along from one family to another: no one wanted me, no one ever stood up for me.

My mom didn't want to keep me, so I was put into foster care. The first foster family took me in because the mother was unable to have children, but when she got pregnant a few years later, they gave me right back. I understand that they weren't exactly rich, but you shouldn't just toss around a child – a person – like that.

In my second family, I was beaten with a belt and slammed against doors, but what I found more unbearable was that they didn't stand up for me either. It was also the first time that I came face to face with the disadvantages of my ethnicity. The family's relatives were racist, which caused a lot of conflict between them, so my foster parents decided to get rid of me. Yet when they had taken me in they knew very well that I was of Romani origin.

Then a third family, who had already taken in three foster children, accepted me, thinking they could accommodate a fourth. We didn't manage to develop the kind of relationship that I would have wanted: we didn't have the kind of affectionate connection that I had imagined. So I took refuge in sport instead. I forgot about everything when I trained. I was driven by a desire to prove myself, to show that I was a better athlete than everyone else. I also believed that if they saw what I was capable of, it would be clear that I was not only a good athlete, but also a good person – that I could achieve just as much as any white person.

It's because all signs pointed to the fact that the others didn't see me as an equal, not even at training sessions. I always kept quiet and went to every training session: twice a day, every day. I started playing handball back in the fifth grade of elementary school. I often went to practice dreading the thought of having to do partner drills again, because I knew I wouldn't have anyone to do them with.

I really couldn't understand why nobody wanted to pair up with me: I was well spoken, a good student, went to secondary school and had good hygiene.

I only point this out because the Romani people are perceived as being foul-mouthed, uneducated, dirty, and shifty. Nowadays we don't even do pair exercises at my training sessions: I don't want the possibility to arise for people – my people – to experience what I had. It may not seem like a big deal, but being left out is a terrible feeling. That's what sticks with me most to this day, even though there were even times when

I had to get dressed on the floor and nobody seemed to care.

This is in the context of a team where the whole point is standing together. On the way home, I was so bent out of shape that I nearly lost it, but it ended up just pushing me even more to show what I was worth.

As a Yemeni woman, I'm seen as an exotic beauty

Following my try at handball but before getting into boxing, I tried getting a job as a receptionist at a gym in Buda. It went so "well" that from that point on, I was sure that my background was the determining factor in everything. Things had been going smoothly at the interview for a while, but then the interviewer asked me about my ethnicity. I was not aware at the time that they couldn't ask such things.

For a very long time I had answered this question by saying that I was Yemeni, just to avoid having to tell the truth. I got the idea from the show Friends: as a Yemeni woman, I'm seen as an exotic beauty, and people treat me in a positive manner. The first thing that comes to their minds about Romanies is that they steal, cheat, lie and swear. But this time I was sure I was going to get the job because I thought the position was a perfect fit for me. So I told them I was of Romani origin. As soon as I uttered that word, the mood shifted. I did not get the job.

Despite my success later on, things were no different. There were countless incidents, one of which I still remember: even after I had won Hungary's bikini model competition, when I went down to a new gym with a guy, they let him in, but not me, saying there was no more room. Of course, the gym was almost empty.

It was terribly humiliating. I'll never forget the embarrassment – imagine trying to build your future, to prove yourself when people treat you like that.

Just a few months ago, the owners of an apartment refused to rent it out to me. When they saw me, they panicked and said it was no longer for rent as a relative had already moved in. I passed by there the following day and saw that, in fact, it was still for rent. I raced home, bought a bunch of junk food and just wallowed in my tears. After I later explained what had happened to my bosses, they told me that the next time something like that happens, I should tell them and they would come with me to the place. That was comforting, but at the same time it's extremely humiliating to have to bring someone white to a negotiation in order to prove that I could be trusted.

My friends and acquaintances tell me not to bother myself with such people. Of course, it's easy for them to say. Just one experience like that every five years is enough to really devastate you because you don't understand why they're treating you like that.

Despite anyone's claim that there is equality and that the Romani people are not oppressed,

given a choice between a white person and a Romani, the white person will be chosen: it doesn't matter whether it's regarding work, sport or anything else – and this holds true even if we perform comparatively better.

I know that this is not just my story: prejudice against the Romani people is firmly entrenched in Hungarian society. And our situation in the job market is more than just difficult: the employment rate of the Romani population is low, and we occupy less advantageous positions in the labor force. The reasons include the fact that a significant proportion of Romani people live in disadvantaged areas with respect to the job market, education, and low employment rates among women.

This series of articles was produced in partnership with the Equalizer Foundation. The Foundation's aim is to promote and support changes that will result in more women leaders in the economic, cultural, scientific and political life of Hungary. Its members believe that decisions made with the involvement of women are more grounded.

Despite being a woman

Boxing was the one area where my background didn't cause any problems, as it is a poor person's sport. Yet here was another situation where I had to fight against prejudice because although there are many Romani boxers, few girls take part. In fact, when I started, there were hardly any women in the ring, and the same was true for kick-boxing. For this very reason I approached my very first trainer saying that I didn't simply want to train and run around, I wanted to compete.

As a woman at the training sessions, at first I wasn't taken seriously – but not because they were crass. As a matter of fact, they were simply of the mind that you shouldn't hurt girls but rather treat them politely and kindly.

But I was the first one to show up and the last one to leave, and I swung hard so that they wouldn't see me as just a pretty girl.

Even so, it still took time for them to accept me, and to this day there's still a guy who always questions what I tell him for some reason. Most of them don't do that to me any more, but that's the result of hard work: respect has to be earned, not demanded. That's the tough part. And of course men can beat me in the ring, but it's not because they're more technical – they just outweigh me.

I never wanted to become a role model

Whenever I hear that today we live in a world where everyone has similar opportunities and everyone is where they ended up based on talent and merit, I always think about what would have become of me if I had stayed with my mother. Or even with the second family who adopted me. Then my life might have taken a wrong turn because they cursed and didn't care much about my education.

That's why I'm glad that more and more places are inviting me to give motivational talks to disadvantaged children. I see the lives they lead. These kids come out of the system at eighteen and don't have anyone. It's no wonder that they steal and swindle. Imagine ending up on the street at eighteen without a job, a place to work, or loved ones – what would you do?

Every year, five to six thousand children enter the foster system and the same number leave. Their prospects are bleak, and they are at risk of homelessness (according to one survey, one in five homeless has spent part or all of their childhood in foster care), prison, and even prostitution.

Meanwhile, these children are constantly being told that they have no chance of a "normal" life. And the prejudice against us is very strong: according to a survey by SOS Children's Villages, 7% of respondents think that the child is at least partly responsible for ending up in foster care. One in three respondents agreed with the statement that people in foster care break the law more often, and one in six said they lie more.

So the kids are in even greater need of stories that show that it is possible to break out of this system. The fact that a girl from a place near Marcali made the national handball team played a very strong role for me. I thought that if she could manage it from a place not far from us, then subsequently I could do it too. That's precisely the impact I want to have, which is why I want to tell them my story.

I am aware that there are athletes who have achieved much greater things than I have, but I put in the work just like them, and yet I am rarely noticed. I have two world championship bronze medals, and I was a national bikini model and a national kick-boxer. In boxing, I took 3rd place in the Hungarian championships. But people don't pay me any mind because they can't identify with a dark-skinned woman. However,

I think that's the solution: to present as many successful Romanies as possible, from as many fields as possible.

Precisely so that people can see that a person of Romani origin can put in as much work as anyone else and can get to where a white person can when given the same opportunities. I never wanted to become a role model – but I would like to see more than just white-skinned Hungarians in competitions, juries, and everyday life. And sooner or later we will get to the point where we no longer need to highlight the fact that we are of Romani origin when listing our achievements.

This is an opinion piece and does not necessarily reflect the views of Telex. At Telex, we believe it is important that the views of others are made known even if we don't necessarily agree. We would like our readers to hear as many views as possible on a given subject.