The Rubik's Cube (originally, the Magic Cube) is a Hungarian success story with few rivals. It has been passed down from generation to generation with around half a billion units sold, and has become a pop culture staple. Nowadays, whenever a comic book or movie is set in the eighties, the cube will almost certainly make an appearance, at least as a part of the scenery. And the name of the puzzle's creator, Ernő Rubik, is known all over the world: if you ask a foreigner to name a famous Hungarian, the most common answer will be Rubik, along with Ferenc "Öcsi" Puskás and Béla Lugosi.

2024 is a special year for Rubik: the inventor celebrates his eightieth birthday on July 13th, and in the spring, the cube turned 50. Since its prototype was first put together, microcomputers and the Internet have become commonplace, and the video-game industry was born – and yet the magic cube has not faded from public consciousness. In fact, it seems to have become a mainstream game like Lego and chess – a fun analogue toy that has its place even in the most digital of households.

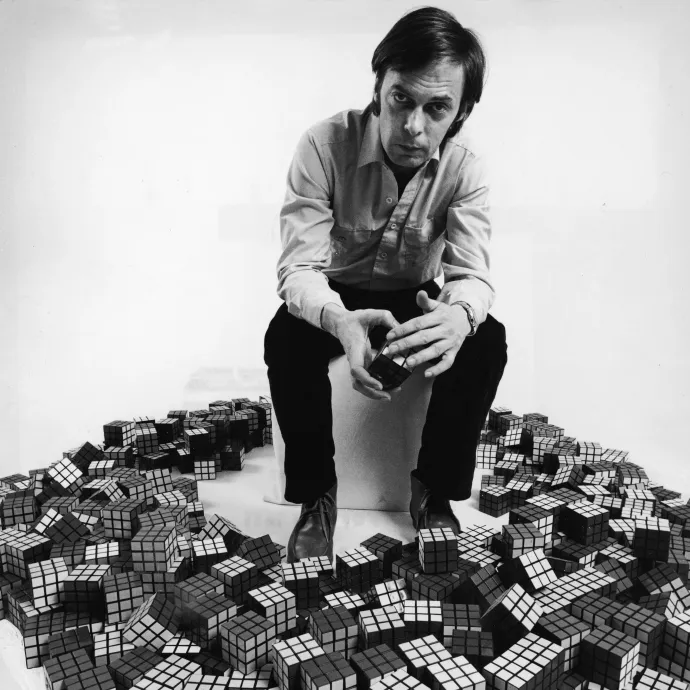

In hindsight, it's easy to acknowledge the ingenuity of the cube that earned it its fame, but initially, children's toy experts didn't see the appeal of it. They thought it too complicated to be sold in large quantities, since a spatial puzzle requires much more mental effort than a toy car or doll. And because the cube was difficult to solve, a sense of achievement was far from guaranteed – in fact, failure is more likely for the first handful of attempts. "During the cube's early years, I spent quite a lot of time at toy fairs demonstrating how to solve it. It's typical of a game that you can't just put on a shelf and watch it sell itself," said Ernő Rubik, who rarely appears in the press, when we interviewed him for Index during the cube's anniversary ten years ago.

The inventor keeps a low profile because he believes that it is not he who is the central figure, but his games. In fact, even when it comes to the cube, it's not even the object itself, but the effect it has had. "It's the fact that it has managed to have such an impact on so many people for so long and has continued to appeal to new generations for decades while the world has changed so radically," he said. The double anniversary offers us a great opportunity to take a look back on this peculiar cube.

27 brilliant elements

Ernő Rubik admits to having been greatly influenced by his father, the aircraft designer Ernő Rubik Sr. Even as a child, the inventor was already tinkering with his father's tools and inherited an engineering approach from him. But the younger Rubik also possessed a strong artistic inclination: he was already working as a metalsmith while in high school, and later, he also took up painting and sculpture. It was in architecture that his engineering and artistic passions came together: in 1967, Ernő Rubik graduated in architecture from the Technical University of Budapest, and then studied interior architecture and design at a postgraduate workshop. He then taught for fifteen years at the University of Applied Arts (now the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design), during which he invented the cube, a feat of engineering and art in itself, one might say.

As a humble gesture, the official chronology of rubik.hu begins with Sam Lloyd's sliding squares game, which he invented in 1873. While that puzzle only consisted in putting together an image or pattern, the cube puzzle required thinking in three-dimensional space. Instead of a square, Rubik sliced a three-dimensional solid (cube) into pieces and thought it would be possible to rotate them around one another so that the pattern of the cube could be scrambled and put back together. A key insight was that to achieve smooth rotation, the edges of the cube elements had to be rounded, an idea the designer got from the rounded pebbles on the bank of the Danube.

In the spring of 1974, Rubik made his first cube: it was a 2×2×2 model made out of wood. He used rubber rings to hold the elements together, and later he tried the same with magnets. Neither solution was satisfactory, as the cube frequently fell apart, but the imperfect prototype provided him with enough insights to be considered the birth of the magic cube. The inventor then set about designing the elements in such a way that they would hold the cube together. Anyone who has taken apart a Rubik's cube might have marveled at the ingenuity of the construction: the center cubes of the six sides are connected to a central element that also facilitates rotation, the 12 edge cubes can be snapped between the center pieces, and the 8 corner cubes can be slid between the edge cubes.

Rubik initially intended the cube to be an educational aid and only when the final 3×3×3 model began to take shape did he realize that his invention would make a great toy. But 1975 proved to be a disappointing year for the inventor. On January 30th, he filed a patent application for a "spatial logic puzzle", but the patent office took its time, only granting the patent two or three years later. On March 3rd, Ernő Rubik gave the cube to Politechnika (later Politoys) for domestic distribution, but the company only started to pursue the matter after the inventor, fed up with their lack of action, imposed a 15-day deadline in December. By that point, it seemed that the toy market might be the way forward, as the National Pedagogical Institute rejected the cube as an educational aid.

From scarcity to overproduction

In 1977, the magic cube finally came onto the market after Rubik found a small company that agreed to produce 12,000 units for domestic sale. Success abroad also came about gradually. At the 1979 Nuremberg Toy Fair, for example, the cube received a lukewarm response, which is not surprising given that it was kept in a display case at the expo and couldn't be seen in action. But word of the cube spread, and anyone who managed to get their hands on the toy quickly recognized its brilliance. And by the 1980s, it was being picked up by business people who wanted to distribute the toy worldwide.

The cube craze took off in the early 1980s, after the American Ideal Toy Company signed a contract to distribute the cube in several countries, with Politoys as the manufacturer. At first, the cubes were only being produced in Hungary: there were plenty of secondary production plants working on the toy, but they still couldn't keep up with orders. As demand for the cube grew, it became increasingly scarce. The shortage was then resolved in the following months by the appearance of counterfeits from China and elsewhere, and after the market became saturated, the cube craze led to an overproduction crisis. In 1980, about one million magic cubes were sold in Hungary, meaning one out of every ten Hungarians had one. Then TRIÁL, the entity responsible for domestic sales, ordered another million cubes by 1981, some of which ended up in Politoys' warehouses, as the manufacturer came close to bankruptcy.

Other difficulties also emerged: while the magic cube had already begun its conquest as Rubik's Cube in the early 1980s, socialist bureaucracy rather hindered Ernő Rubik's success. The head of Politoys prohibited the inventor from traveling abroad, temporarily blocked the publication of a book on how to solve the cube, and even accused Rubik of illegal foreign trade in 1981. To make matters worse, the company took so long to produce another one of Rubik's toys, Rubik's Snake, that counterfeits from the Far East were first to appear in the country.

By the second half of the decade, with the legal disputes and logistical problems having been sorted out, things had returned to normal. By then, Ernő Rubik had established foundations to support talented inventors, and in 1983 he founded the Rubik Studio. Meanwhile, his mind stayed busy: in 1985, while new versions of the cube were being developed, he invented the magical squares game of Karikavarázs ("Ring Magic"), known in English as "Rubik's Magic". Released in 1986, it too was a great success and has been in production ever since – perhaps now with stronger strings than at the time of its release, as a number of people made money on the side by restringing broken instances of the game.

Pop culture player for half a century

"There's simply no end to the cube's story – the Internet made me realize this when I had come across grandmothers that crocheted cubes", said Ernő Rubik 12 years ago, and like his cube, this statement hasn't aged poorly: to this day, the cube has remained steadfast in global pop culture, and has even become a cultural icon in some parts of the world. It crops up from time to time in the media and the arts: sometimes as a decorative piece, sometimes as a background element, sometimes as a key motif or even protagonist. Clearly, it has inspired a wide range of artists for decades.

Much of the research on the Rubik's Cube takes place in the mathematical field of combinatorics, however, the cultural/pop-cultural impact of the cube is no less intriguing, which is not simply attested to by the cube-crocheting grandmothers: in Rubik's 2020 book Cubed: The Puzzle of Us All, he writes that he originally planned to include an album of pop culture references in the book. He ultimately scrapped the idea but did not explain why.

The significance of the cube is illustrated by the fact that in 1981, the Museum of Modern Art in New York included it in its collection of architecture and design. Then, for its 40th anniversary in 2014, it was the subject of a 650-square-meter exhibition at the Liberty Science Center in New Jersey, which went on to tour the world for seven years. As to whether there will be such a global event this year, the 50th anniversary of the cube, remains to be seen. However, looking back over half a century, we can see that Rubik's invention has become not only an icon, but also a symbol. What it embodies above all – as Ernő Rubik himself says – is how complex things can be represented in a simplified way. That is why the advertising industry and popular culture are so fond of employing it. Below are a few examples.

Music: from Spice Girls to Genesis

A lot of musicians have drawn inspiration from the Rubik's Cube, which is evident in their lyrics and/or music videos. From the Spice Girls' "Viva Forever" to Jennifer Lopez's "Ain't Your Mama" and Genesis' "Land of Confusion". One that stands out is the 1981 song "Mr. Rubik" by the English band Barron Knights, with its humorous lyrics about the agony of solving the cube puzzle. The song was released on the band's album Twisting The Knights Away, which features a Rubik's cube on the cover with the band members depicted on the faces of the pieces. In music clips involving the cube's cameo appearance

the cube is often used as a metaphor for the complexity of life, but it is just as often used as an allegory for human intelligence.

(Even more Rubik-related video clips can be found here.)

Film: from the Simpsons to near-speedcuber Chris Pratt

Perhaps even more film and TV directors have been inspired by the Rubik's Cube than musicians. It appears in popular series such as the Big Bang Theory, Rick and Morty, and the Simpsons. It's impossible to list the number of movies in which it has made cameos, but it includes many big-budget films such as Armageddon, WALL-E, the Pursuit of Happyness, and Being John Malkovich. Sometimes it's just a set piece used to evoke an 80s vibe, but in many cases it's an integral part of the story and it serves to convey a character's sharp mind. Of course, there are also times when cube is trending off the silver screen: for example, when Chris Pratt solved one in 3 minutes with the greatest of ease – even partially without looking – while giving an interview. For those interested, the cube's most striking cameos and other cinematic appearances have been collected and cataloged by front-end developer Arjan Eising, and it's possible to get lost in the archives for hours.

Sculpture: easy to scale up

Most sculptors likely saw the potential in the Rubik's Cube, as its minimalist appearance made it easy to scale up. The Rubik's Cube statue at the entrance to Graphisoft Park in Budapest is an example of steampunk-inspired sculpture (designed by Ernő Rubik himself), while the city of Százhalombatta contains a rather substantial sculpture erected for the cube's 40th anniversary that even lights up after dark. And it's not so difficult to carve a pop-up sculpture out of it either, as American artist Kyle Toth (note the Hungarian last name) did in Cleveland a few years ago.

Although not a statue, there's the world's most expensive Rubik's cube, the Masterpiece Cube. The small 3x3 cube was made by Diamond Cutters International in 1995 to celebrate its 15th anniversary. Each side is colored with intricately arranged gemstones such as green emeralds and red rubies. It is estimated to be worth $2.5 million (other sources say only $1.5 million), and was on display at the massive Beyond Rubik's Cube exhibition mentioned earlier.

Architecture: Rubik buildings are all over the world, yet Hungary has had one in the pipeline for more than a decade

A number of buildings have been inspired by the cube, probably for similar reasons as with the sculptures. Some of the best known examples include The Children's Gallery in Melbourne, the City Library in Stuttgart and the Discovery Cube in California, a non-profit science center for children. The very house of Ernő Rubik in Budapest's 2nd district also features a peculiar tower: the architect-turned-inventor designed it as if it were 3 cubes stacked on top of one another.

In 2012, the Hungarian government announced plans to construct a Rubik's Cube-shaped mimetic building next to the Rákóczi Bridge, to be called the Rubik Art Museum. In the official 2012 statement, Balázs Fürjes said that "there has never been anything like it in Hungary". Well, with the way things stand, not only had there never been anything like it at that time, there hasn't been anything since then either, despite the cooperation agreement signed by Viktor Orbán and Ernő Rubik. As to where the investment stalled out, it is a mystery; we have repeatedly contacted the Ministry of Construction and Transport, headed by János Lázár, over the past few weeks, but have never received a reply. We also reached out to Budapest's officials to find out what they know about the project. The Mayor's Office said that "the city administration that took office in 2019 has not received any government enquiries about the Rubik Museum, and there have been no consultations regarding the matter." Meanwhile, the nearby Austrian city of Linz didn't sit on its hands: in 2013 the city saw the transformation of a building into a giant Rubik's cube whose very lights can be manipulated with a real Rubik's cube.

Advertising: good enough even for Mickey D's and great for country branding

As the Rubik's Cube is both popular and easily identifiable around the world, even creative directors at advertising agencies are keen on using it. It regularly appears in print and video ads. Among the funniest ads is certainly the one from McDonald's in India, and one of the most innovative ones is the Citroën C1 commercial. Other ads involving the cube can be found here and here.

It's also great for boosting the country's image: in 2023, a huge mural of a Rubik's cube was unveiled in central Seoul. The metal surface, 80 meters long and 10 meters high, features an image of Ernő Rubik holding a cube next to the image of an even larger cube. The monumental street mural was created to mark Rubik's anniversary this year. The project was a joint effort between the Liszt Institute (Hungarian Cultural Center – Seoul) and an agency of the Korean Ministry of Culture, and was carried out by Neopaint Works.

In Hungary, those who sing its praises and those who run around dressed as one

After the cube hit the market, it goes without saying that Hungary was inundated with a lot of related merch (only it wasn't called that back then). In 1982, for example, the Hungarian Post Office issued a stamp for the World Rubik's Cube Championship in Budapest. Also that year the band Color sang about the same puzzle-solving agonies as the Barron Knights did in their song "Bűvös kocka" ("Magic Cube").

Then there's the song "Rubik Ernő" from 30Y's fourth album, and although it sounds like lyrical nostalgia for the eighties, lead singer Zoli Beck said in an interview that it was a key song, also because it was the last song he wrote about his father. In 1990, Péter Tőke wrote the novel The Power of the Cube (A kocka hatalma), which delighted many readers. Another compatriot, István Kocza, not only took part in the European Rubik's Cube Championships, but also sported a Rubik's cube costume at long-distance races whenever he could. The cube also appears in a scene from the time-travel, action-comedy film Hungarian Vagabond (around 38 minutes into the movie).

The toy of choice for liberated kindergarten girls in neighboring countries

Looking around at our neighboring countries, we catch glimpses of the cube's past 50 years: in 1984, for example, a Czech film was released called "Rubikova kostka" ("Rubik's Cube"), directed by Jirí Svoboda. The 1982 Czech song "Holky z naší školky" ("Girls from our kindergarten") was a veritable declaration of liberation, as little girls abandon their dolls for Rubik's cubes.

In 2011, a Rubik's cube signed by the inventor was auctioned off in Poland, and an image of a robot at the Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence shows a robot handing a Rubik's cube to a researcher – bringing us full circle to the cube's symbolic representation of a sharp mind.