Even the highest medal of honour could not save him from dying in a labour camp

At the end of February 1933, when the American film Grand Hotel premiered in Budapest cinemas, the nation's biggest celebrities were present at the screening – even Regent Miklós Horthy and his wife accepted the invitation. The romantic film's lead role, that of a Russian ballerina was played by Greta Garbo. The movie was a great success in the United States, which is why everyone looked forward to the Hungarian premiere with great enthusiasm. The enthusiastic crowd outside the theatre cheered the arriving stars and dignitaries. Two-time Olympic champion fencer Attila Petschauer was the one announcing the arrival of the guests, and he also reported on the radio about what was happening inside the building and what kind of outfits the guests were wearing.

At the time, the newspapers were constantly speculating about the future of the supremely talented Petschauer, who was 28 years old and was at the centre of social life, but no longer wanted to continue fencing. "I've lived for my sword, from now on I want to make a living from my sword" was his famous farewell to the sport. The top athletes of the day were not well paid, and at the time athletes were still competing as amateurs (except in football, where professionalism was introduced in 1926). The main problem in the life of many Olympic heroes was how they would succeed in life beyond sport.

Fencing made him a national hero

Born in December 1904 to a Jewish family in Budapest, Petschauer was introduced to the sport before high school in 1919 and quickly became hooked. He first trained with István Fodor, and then with Italo Santelli, who later coached a string of national teams.

"You'll make a great champion"

– the coach promised him. In 1925, Petschauer was already on the national team and came in third at the European Championships. He practised eight hours a day, obsessively honing his movements even on the street or while on holiday, it was thus not by accident that he was considered the most technical competitor of the era, a virtuoso of the blade. Aladár Gerevich, who later became the most successful Olympian, recalled that even when his companions told him before a bout whether they wanted a head or a belly strike, they still weren't able to parry it, despite knowning exactly where Petschauer was going to attack.

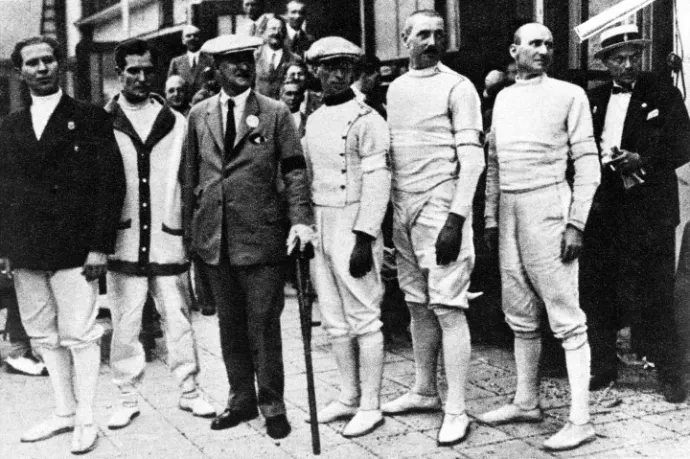

In 1926, he won the silver medal in the individual event at the European Championships in Budapest, but a year later he withdrew due to an injury. This did not set him back though, not even temporarily, and he was considered a favourite for the 1928 Olympics. At that time, the team event was held first, followed by the individual event. The national fencing team was fuelled by the desire to get back at the Italians, who had won the Olympics four years earlier. The two teams reached the Olympic final easily, and the big clash was on. Petschauer won all three of his matches, he was the Hungarian team's finishing man – an important position of trust – and when he stepped on the piste for the fourth time, Hungary was leading 8:7. If he were to lose, the score would be 8:8, and a draw would give the Italians the gold medal. If he were to win, for the first time since 1912, Hungary would be Olympic champions again.

His opponent, Renato Anselmi was 12 years his senior and much more experienced. Tensions were so high that his teammate, Ödön Tersztyánszky left the room and went to the corridor, while the wife of Sándor Gombos, who had lost the previous bout, fainted. The Italians didn't have nerves of steel either, and Puliti had to be cared for by a medic after he suddenly fell off his chair. According to reports, after uttering his characteristic battle cry, ‘ollala’, Petschauer was chalk-white when he took his place on the piste. He had won a total of 19 bouts in the Olympics, but if he didn't win his 20th, the glory would be lost.

He started with two hits, but the Italian caught up and had a chance to even the score at 4:3. Petschauer then used his typical dynamic charging attack: he chased his opponent to the end of the piste and when Anselmi was in a vulnerable position, he put the last decisive hit on his chest. It was such a clear and beautiful hit, that his teammates didn't even wait for the jury's official verdict, they rushed to the piste to celebrate and lift the hero of the final on their shoulders.

After the victory, Petschauer told the daily, Esti Kurír:

"It was a terrible feeling to see the Italians come up. I was overcome with desperation, every part of me trembled at the thought that everything depended on me, that the fate of the gold medal depended on me. I summoned up all my energy, and plunged into the fight with a kind of wild desperation, and I am happy, ecstatically happy that I made it. I won and with this victory, we won the team competition."

The athlete was exhausted from the competition, and this is what later evaluations attributed his failure to win the individual event to. Tersztyánszky finished with exactly the same score after nine wins and two defeats in the twelve-man round-robin final. According to the rules, their individual bout had to decide who would stand at the top podium. Petschauer was defeated 5:2. Although he won 20 matches in the singles, he could not win the individual event after the team victory and did not become a double champion.

On his return home, he gave an impromptu speech at Keleti Railway Station, which thousands of people applauded. The correspondent of Magyarország noted down the following thoughts: "We went to Amsterdam to compete with the best in the world, to show the best in the world what Hungarian strength is worth. We were sent out by a miserable little country of eight million people. With the whole world standing against us, we fought and struggled for the honour of Hungary. We knew that this was our duty, but we also felt that we had to do more than what our duty dictated. We felt the trust of the nation and we felt that we had to be worthy of that trust. Many times the victory was won through the gnashing of teeth and tears. The reason why we fought with such strength was to show those who see every flash of the Hungarian sword that there are strong, fierce Hungarians living here, who have preserved all the virtues of their warrior ancestors and who, with sword in hand, will stand up to the whole world for the integrity of Hungary."

It was not only his speech that made him a favourite with the public, but also his brilliant intellect. He had an exceptional sense of humour and was good friends with the famous and witty writer, Frigyes Karinthy. He was friends with actresses and dancers, too.

By 1932, when he travelled to the Los Angeles Olympics, he was a star, and his team won the gold medal at the Games. There was no trace of suspense in the final against the Italians, as this time, they overpowered their opponents 9:2, a domination never seen before. He finished fifth in the singles, which he considered a minor disappointment.

Petschauer then tried his hand at journalism, reporting from Hollywood for the theatre magazine Színházi Élet. He did not return home with the Hungarian delegation, but stopped in New York and then Washington, where he was received by the US President, and although he seriously considered settling in the US, he ended up coming home later that winter in the end.

In 1933, he tried his hand in the media, and was given a column entitled Honest Talk at the Est newspaper. Boldly enough, he also wrote about football. A critical article he wrote caused a big row in the fencing federation, and he resigned from his position as councillor. He did not compete at the 1933 European Championships in Budapest, but he did have a film role that year. He was good friends with Gyula Csortos, a popular actor of the time, and through the extensive contacts of Csortos' daughter, he arranged a job for himself in 1938, when it was no longer easy for Jews to find work. His admirers competed for his friendship, they were all happy to do something for him.

On several occasions, when it was possible, he protested against the anti-Jewish laws, and even left the piste because of a ruling he considered unfair. Some of the political elite, who had come to the competition just to see him were thus left without the opportunity to admire his movements and knowledge. He went to the ’36 Olympics in Berlin as a newspaper correspondent.

In 1940, after the outbreak of the war, in his diary, he grievously recorded his thoughts about how evil humans can be. He could not have imagined at the time what calamities were about to befall him and what cruel hardships his last months would be filled with.

Fatal mistake

Petschauer firmly believed that he could not be harmed because after his Olympic victory, he had been awarded the highest state medal and he believed that the Signum Laudis would save his life, there was no way he would be taken away with the other Jews. He even had two minor medals, each of which could have given him an exemption, however, they all proved to be insufficient.

He was summoned for labour service to the headquarters in Veres Pálné Street on 27 April. He went there dressed in spring clothes, expecting nothing bad, because he wanted to clarify his situation. From there, however, along with 40 doctors, he was immediately taken to Keleti railway station and loaded into a railway wagon.

According to the upsetting recollection of one of his fellow captives at the labour camp, once they arrived in Nagykáta, Petschauer approached Lieutenant Colonel Lipót Muray and addressed him with great respect as "Honourable Sir", telling him who he was and what medals he had received that could have exempted him from labour service, and that it must be due to a fatal mistake that he was there. Muray replied that he should shut his mouth, that he did not deserve the medals and that those who sent him there knew exactly why they had done so, so he should get back in line. The response shocked Petschauer and it became clear to him that he could no longer rely on his former merits. (Muray, known for his sadism, was hanged as a war criminal in Budapest on May 1, 1945.)

His fellow national team members tried to speak up for him, one of them even reached out to Horthy's immediate circle, but said there was nothing they could do because by that point he was no longer in Hungary and Hungarian law did not apply to him abroad.

Those among the labour service workers who recognised him, encouraged him that this misunderstanding would be cleared up and he would for sure be freed. Petschauer used his sense of humour to entertain his companions, and told them about the Olympic atmosphere and the glamour of America. He couldn't stay cheerful for long, however, as he had not even brought warm clothes with him.

He didn't often talk about how he got into this situation, but he had a theory as to why he was taken away to labour service despite his medals. Once, in a hotel in Vienna, a high-ranking military officer yelled at him and called him a Jew, to which he responded by slapping him. They had a duel, and because he was much better skilled, he cut the officer's face. Petschauer suspected that this was the officer's way of taking revenge on him for the scar, as he had been promoted to the general staff of the army by then.

While at the labour camp, he was constantly humiliated, his Olympic gold medals were made fun of, and he was mockingly told to show everyone what he was the world's best at. According to recollections, the guards were eager to make fun of him. His final agony began once the cold winter set in at the camp in Davidovka in today's Ukraine. He was emaciated, plagued by illness and no longer able to work.

During his last weeks, he bumped into Kálmán Cseh, who competed in the equestrian events at the 1928 Olympics, and hoped that perhaps Cseh would help him by having him taken to hospital. Years before, when they were on the train, travelling to Amsterdam for the Olympics, Cseh had told him: “You'll bring glory to the name of Hungary with the sword, and I'll do it on horseback”. But the lieutenant colonel did nothing for him when they met at the front, except for waving to his aide to make the Jew dance. (Cseh did not deny this at his later trial in Budapest.)

Petschauer eventually contracted typhus. He got so sick that he was unable to stand, and was rushed to a Soviet war hospital at the last minute, but by then they weren't able to help him. He died 80 years ago, at the end of January. In the United States, a competition is regularly held in his honour, and film director István Szabó paid tribute to him in his film Sunshine.

Sources: Élet és Irodalom, 1976/1 and 3, Virtuális Sportmúzem