After obtaining his PhD at the University of Debrecen in 2013, Amir Mosavi, a native of Iran, decided to settle down in Hungary. He specializes in applied informatics and data science. Big data, machine learning, artificial intelligence, deep learning algorithms, decision-making, and predictive models – such are the buzzwords pertaining to his domain. He maintains active relations with several institutions, but since 2013 his main position has been at Óbuda University, where he is an associate professor at the Institute of Software Design and Development of the Faculty of Informatics. Despite only being in his thirties, Mosavi has already published hundreds of scientific papers.

Óbuda University is a thriving institution. It also underwent the much-debated higher-education model change (from state-managed to foundation-managed) in an orderly fashion – as was announced in September by Mihály Varga himself, the Minister of Finance, who is also the chairman of the board of trustees of the university's foundation. The university also performs well in international rankings: in October of this year, one of the most prestigious rankings, the UK-based Times Higher Education (THE), ranked it as the fourth-best Hungarian university in 2023, and among the top 1200 worldwide.

The success of Amir Mosavi and that of Óbuda University appear to be linked, and the correlation reveals some rather interesting statistics.

The super-researcher behind the statistics

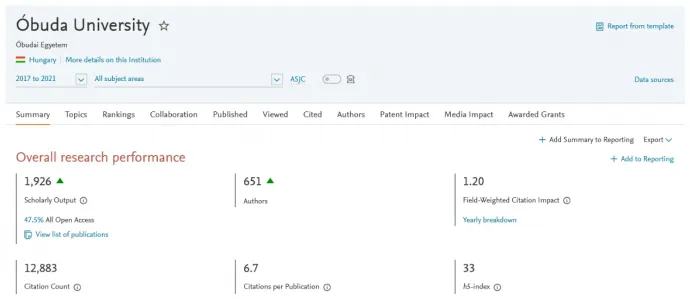

One of the most important tools for measuring research performance is Elsevier's huge scientometric database, Scopus. The authors of THE's rankings based their latest list on papers (and their corresponding citations) published at the universities between 2017 and 2021. A search of Óbuda University in Scopus shows that during this five-year period, a total of 1,926 papers were produced at the university by 651 authors, and they were cited 12,883 times (the screenshot below shows the figures at the end of October).

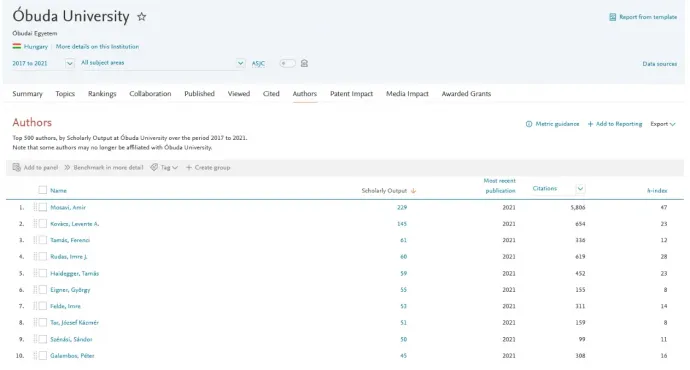

By clicking on the Authors tab, we see who contributed the most to these figures in the university's name. The ranking includes several institute leaders, including the rector, Levente Kovács, and a biostatistician who gained a lot of media attention during the Covid epidemic, Tamás Ferenci. Such findings are not surprising apart from the top spot: the aforementioned Amir Mosavi who has an astounding lead of 229 studies and 5806 citations (as of the end of October). In other words,

of the university's 651 authors, Mosavi accounts for 12 percent of its publications and 45 percent of its citations.

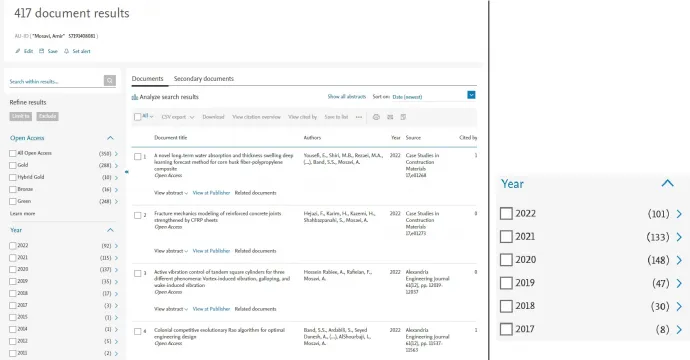

If we break down the number of papers written by Mosavi by year in Scopus, we again come up with some interesting figures. The 35 publications in 2019 alone could be considered praiseworthy, but what happens afterward is downright superhuman: In 2020, he contributed to 137 papers, meaning that a paper that he co-authored was published every 2.7 days, including weekends. With 115 publications, 2021 was another busy year for Mosavi, and he is already approaching 100 this year. Interestingly, these numbers were even higher before I reached out to him. Scopus is constantly being updated, so this shouldn't necessarily be surprising, but the scale and timing of the change is something to think about. The screenshots below show mid-November on the left and the end of October on the right:

Adding up the numbers, it appears that there are more than the 229 studies mentioned above for the period 2017-2021. One way this is possible is if Mosavi also publishes work in affiliation with other universities. Alongside his work at Óbuda, he has also been active for many years at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, the Queensland University of Technology, and Oxford Brookes University. From the Web of Science database, it turns out that in 2021 Mosavi was simultaneously affiliated with 12 different institutions.

The Scopus figures are also used by the organization that produces THE rankings when rating universities – granted, it doesn't work directly with Scopus data, but with SciVal, a paid tool from Elsevier that provides deeper analytics. THE ranks universities according to the number of points they score, which in turn is based on five sub-scores that contribute to varying degrees. Here are the five areas along with the percentage that they influence the overall score in parentheses: teaching, i.e. learning environment, (30%), research (30%), citations (30%), international outlook (7.5%), and industry income (2.5%). Óbuda University's score is somewhere between 24.4 and 29.7 (this is the range of the rankings between 1000 and 1200, as THE doesn't provide more precise data than this).

Of the five areas surveyed, the university's sub-score for citation was 45.5, while in education and research it scored 15 and 14.6 respectively. In other words, citations boosted the university's overall score substantially.

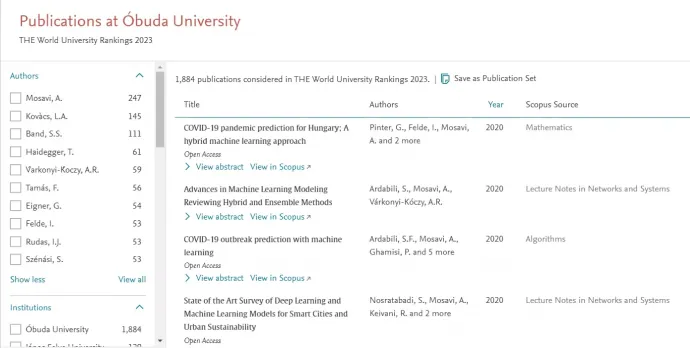

When calculating the citation sub-score, THE takes into account a measure called Field-Weighted Citation Impact (FWCI). This indicates how the number of citations received for each publication compares to the average number of citations received for all other similar publications in the given subject field. In SciVal, it is possible to see exactly which publications THE has calculated the FWCI for because the software aggregates these studies in a separate interface. Here we also find a ranking in which Amir Mosavi leads with 247 publications:

The data of the studies that influenced the university's THE score (1884 in total) can be downloaded in a large table, which also includes their FWCI number. Averaging these over the entire university gives an average of 1.23, as indicated on one of SciVal's summary pages (this is roughly the same average as that of the Vienna University of Technology, which is in the top 500 in THE's ranking). The FWCI average of the 247 papers co-authored by Amir Mosavi is 4.07. The FWCI average of the 1637 papers without Mosavi's contribution is 0.80. All this suggests that Mosavi may have made a significant impact on the university's FWCI average and through it the citation sub-score, and ultimately Óbuda University's ranking in THE's top 1200 worldwide.

It typically takes years for scientific studies to reach the stage of publication. Managing so many studies at the same time is an organizational feat, but then there's also the task of producing the content, which spans a wide range of topics – as Mosavi models and runs algorithms on almost everything from epidemics and landslides to the stock market, diarrhea, mortar, and diesel engines. Of course, the researcher from Óbuda University does not work alone – from his publication list on Google Scholar, it is clear that he is always involved in papers with several authors. He often collaborates with foreign researchers (Iranian, Vietnamese, Chinese, Canadian), and although there are Hungarian names among the co-authors, they have been noticeably in the minority lately.

Heaps of paperwork

Having discovered all of this, I naturally had questions for Amir Mosavi, who I managed to get in touch with. He provided a plausible explanation for his incredible productivity: he has worked hard over the years to build up a network of researchers, which he now manages. "I travel a lot, visiting institutes on several continents and meeting with renowned researchers from a wide range of disciplines. I also have an eye for talent, as over 180 researchers have written their first publication with me," said Mosavi. He explained that a paper can indeed take years to complete, but he keeps up the pace with the help of his many co-authors by managing the majority of the publications:

"Most of the time I come up with the concept of the study and the methodology. I also have a say in the title, the abstract, and the presentation. Finally, I check the publication according to high-quality standards. All this amounts to a lot of paperwork."

Mosavi appears reliable, mostly publishing in the top two quarters of the SCImago portal's classification system for journals (i.e. Q1 and Q2 journals).

The researcher referred to data science as the "heart of science". "It's a very exciting field and people from all over the world are coming to us with the need to model something. And we have methods and algorithms for almost everything," he said. He says that, in addition to the loads of work, this also results in the rapid pace of his publications. However, he claims that he only stands out in Hungary, as there are plenty of equally prolific researchers in other countries.

As to why Hungarian researchers have recently been in the minority among his colleagues, Mosavi explained this partly by the fact that Hungary is a small country with few researchers in his field, and partly by differences in attitude. He said that because of his ethnicity, he generally has to work harder for recognition in the EU and has not had this problem in many non-EU countries.

When I suggested that his outstanding performance may have made a significant contribution to the university's citation score and thus its position in THE rankings, Mosavi strongly disagreed. He argued that ranking systems normalize data so that rankings remain independent of the progress of a discipline or the productivity of a few researchers.

The dawn of 'publication factories'

As a matter of fact, the exact algorithm of THE is not known, as the organization does not disclose all the details of its methodology. However, it is perhaps the most transparent ranking body, and the FWCI averages reported in SciVal make it quite clear that Mosavi may have boosted the university's average by a large amount. Prior to writing this article, I talked with more than ten researchers and experts, who asked to remain anonymous, and they provided valuable background information in addition to interviews. Among them were two experts in scientometrics, both of whom said that while THE may indeed weight Elsevier's data, a citation spike like Mosavi's almost certainly correlates with the subscore.

I also wanted to find out more from THE itself, so I sent some questions to the organization's main email address and to its regional director, Nicolas Cletz. The organization did not deny the possibility that Mosavi's result drove up the citation subscore, and indicated that it had even brought the matter up with Elsevier and concluded that Mosavi was a "rising star" with links to several institutions.

It was also pointed out to me that the example of Mosavi is indeed not so unique – so much so that in 2018 an investigation on these "two-legged publication factories" was printed in Nature. The authors of this report looked at scientists who published at least 72 papers (or one every five days) in any year between 2000 and 2016 and found more than 9,000 such individuals. (Mosavi didn't qualify for this club at the time, by now he has.)

The researchers conclude that the number of hyper-prolific authors is increasing significantly each year, which raises important questions in scientometrics, such as the evaluation of certain disciplines or the lack of a clear definition of what constitutes an author in the scientific community.

Even in Hungary, there are other prolific authors besides Mosavi, such as the rector of Semmelweis University, Béla Merkely. It is even easier to find similar ones abroad, even among Mosavi's co-authors: including Shahaboddin Shamshirband, who has more than 150 papers with Mosavi alone, according to SciVal. But another good example of a foreign publication-generator is the Japanese materials scientist Inoue Akihisa, the record holder highlighted in the Nature article. Although he has been less active in recent years, he has 227 publications from 2007 alone.

Incidentally, Cletz was an invited speaker at a recent conference on excellence and ranking organized by Óbuda University on November 4th. It is not unusual for THE and a university to have direct contact – the organization even has a consultancy service that universities can order. According to Cletz, Óbuda University did not request this kind of collaboration from the organization for the latest ranking, but it had done so previously. The fee for the service is not public, but according to institutional rumors, it doesn't come cheap.

Fitting into the strategy

For years, one of the main ambitions of Óbuda University has been to move up the rankings, and this was one of the major promises made by Rector Levente Kovács when he took up his post in 2019. And, of course, Mosavi can only be one element of this success, as there are other prolific and/or highly cited researchers alongside him, as well as several management measures to improve the ranking. For example, stimulating research through continuous external and internal calls for proposals and intensive workshops, or attracting professors with good reputations to the university. "There are professors who we don't burden with teaching or other things. They are only expected to publish," said one source.

The rector of the university readily answered my questions. He confirmed that the development of the three most important factors for the ranking – teaching, research, and international recognition – was a key element of his strategy, and the fourth was knowledge transfer. The university has prioritized four research areas, one of which being artificial intelligence. The administration has also developed a research incentive scheme. The rector had only words of praise for Amir Mosavi's achievements. "Associate Professor Mosavi has a broad network of research contacts and works with international research groups that also have an outstanding track record. Now all this seems to have 'ignited', resulting in numerous publications. It should be noted that in many cases a researcher can become a co-author of a study by providing a leading idea or advice for research that has hit a wall. With a wide network of contacts and a solid research background, this is what makes it possible to suddenly have a large number of publications, which might then be reflected in citations within a short period of time. We would be delighted to have more researchers like him," wrote Levente Kovács.

Systems and flaws

Of course, it is not up to a journalist to determine the merit of a publication or the extent to which its authors contributed to its creation, and I wouldn't presume such a role in Amir Mosavi's case either. His network seems to be functioning well. I don't doubt that he's put a lot of work into it. He's not doing anything illegal, and his series of publications shows up nicely in the statistics. It is nevertheless a little absurd that a scholar who puts out yet another article every three days – but which took years to complete – and who works only with foreign co-authors on a large part of his publications, can make a significant contribution to the ranking of a Hungarian university.

In addition to the prestige value of a ranking, this could also be a financial matter. With the remodelling of universities, their funding structure has changed and institutions have to comply with so-called indicators to create a level playing field. Part of the money they receive is in proportion to their performance against these indicators. One of these indicators is publication output,

meaning that ultimately, millions, if not billions, of public funds may ultimately depend on these metrics.

However, the ranking systems are not perfect – in fact, there is virtually a professional consensus that they are methodologically flawed – as Qubit recently reported. THE has also received a lot of criticism, in particular for its citation counting methodology. Partly in response to these criticisms, the organization is in the process of reviewing its evaluation system and has already made this clear. The board of trustees even responded to me with regard to this issue: "In particular, the citation metric, which is based on the FWCI, will be significantly modified."

Ultimately, another important lesson is that the way science works has changed a lot in the last few decades, and universities have also adjusted to this – sometimes in ways that may be questionable from an ethical point of view with regard to science.

According to Scopus, one of the best-known Hungarian scientists, Abel Prize winner and former MTA President László Lovász, published 221 papers over the span of three decades. Katalin Karikó, whose name was often mentioned in the run-up to the Nobel Prize announcements, published 106 papers in the same period. Amir Mosavi, on the other hand, has published 345 papers in the past three years alone.

This is telling if you consider that the three of them conduct research in different fields. Getting published and making it onto scientometric lists is now a substantial international business, and research performance is much more reduced to metrics than it was a decade or two ago. This is something that researchers have to live with, often forcing them to make serious compromises in order to get results. "At the beginning of my career, I would have thought it unthinkable to pay to get a paper published, but nowadays it's quite commonplace," said one source.

Still, despite their flaws, ranking systems have a huge impact on the perceived prestige of universities, and indirectly so does the competition of publishing on the spending of taxpayers' money. Hence the fierce competition between universities for the best ranking – and the unsurprising emergence of 'publication factories'. But not everyone can relate to this approach. "If performance is assessed on the basis of distorted indicators, it can be detrimental to the scientific community as a whole and therefore to the country," said one academic source. "If we have a flawed picture of how universities are performing, there's a risk that we will make wrong decisions to improve performance, for example by not rewarding socially beneficial behavior that genuinely promotes research and education."

As for Óbuda University, their goal for the near future is to land in the top 1000 of THE's ranking.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!