If you're afraid of change, you may as well just get pickled, jarred, and given your pension check

By now, it is practically a platitude that in the future one of the most useful skills for a person to have will not be knowing the exact date of the Mongol invasion or the height of the highest mountain peak, but the ability to adapt. And when faced with the question of how one can undergo decades of constant "fresh starts", we only have to look to Kati Süle's life for the answer. We met with her several times this past spring and summer and talked not only about the benefits of adaptation but also about what constant change does to a person's life; how a seemingly privileged life can be in fact not exactly as such; how to know when to say 'no'; and how one might reach the peak of their career even when they are 80 years old. After all that, the fact that, even in her 60s, she dares to wear clothes she feels good in is practically a bonus.

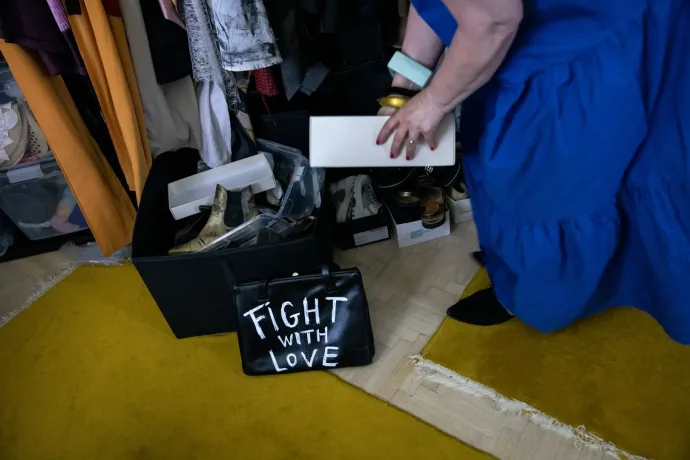

Just over a decade ago, Advanced Style, a fashion blog focusing on the stylistic outfits of seniors, was launched in New York. The blog is run by photographer Ari Seth Cohen, who takes pictures of extravagant, bohemian, and colorful elderly men and women on the street. They don't come off as attention-seeking eccentrics, but rather individuals who are true to themselves and pay no mind to what others might think of them. Initially, we simply set out to see if there were any such individuals here in Hungary. That is when we came across Kati Süle. Then, over the course of several interactions, we gradually worked our way from her extravagant looks to the fascinating depths of her personality.

"If you want to know how much something costs, just ask," – we're standing in a showroom on Andrássy Avenue, in the store of an internationally renowned Hungarian label, where Kati and her fashion school students are doing fieldwork. Kati teaches the elements of style to the students at the Krea Design School, and the subject matter is high-end fashion. They started their field training a few weeks ago at a second-hand store, which was followed by a visit to a vintage shop. Now they are exploring the trendiest brands in the kinds of boutiques that the average person would most likely feel uneasy entering – if they dare to enter at all. Kati, however, is unfazed: she comments, critiques, chats, and asks questions.

As Kati was born the year of the Hungarian Revolution (1956), it was just a few years ago (around the time she began teaching at the school) that her peers were warmly shaking hands as they received their retirement gift baskets. But it's just the other way around for Kati in more ways than one – she is just now starting to come into her own. Rather than a visit to the boutique on Andrassy Avenue, our article could have very well started off at any one of a number of scenes from her life: during one of her strenuous workout sessions, on the set of a film shoot that she had with an airline, at a fashion show in Sopron where she presented her clothing, or as she was chatting with one of her daughters and grandchildren who live thousands of kilometers away.

Of course, there's no recipe for maintaining vitality in old age that works for everyone. And Kati Süle's story is no Disney film either – rather just the right blend of luck, self-knowledge, and ambition.

Kati's parents were economists, and her mother was a bona fide modern woman: she held a management position at a foreign trade company in Budapest. She was passionate about standing up for others and a feminist in the best sense of the word. Her father was a diplomat, which is why Kati and her family went to Ankara when she was just a few months old. Between then and her university years, she had to adapt to many new life situations and many new people across several countries, including visits to the family's home base in Budapest from time to time. "I was socialized by constantly getting exposed to new communities. As such, my primary traits became the abilities to adapt and stay flexible, which can be applied to all kinds of domains." We'll touch on this again later – for now, let's just say that Kati has never been afraid to change workplaces, cities, jobs, or even professions, even as she approached her senior years and beyond.

She attended a Franciscan elementary school in Istanbul, completed two years of high school in Budapest, and then finished her secondary education in Denmark. Despite being an avid ceramist, she felt her skills were not sufficient for the University of Applied Arts in Budapest. Her sibling followed in her parents' footsteps and became an economist, but Kati looked elsewhere.

She began her higher education in art history and English studies in Denmark and eventually graduated from Budapest's ELTE, where she obtained a degree in art history and English language teaching. Interestingly enough, although she had completed two years in Denmark, she nevertheless decided to start her university education all over again when she returned to Budapest. "I was fed up with always being dropped into some social circle, so I wanted to start from scratch, which was a good decision because my closest friendships stem from there," she explained. After obtaining her degree, there was one thing she was sure of: "I knew I didn't want to work in a museum. It wouldn't have been a good fit for me – I simply would have gathered dust like a can of preserves." This marked the beginning of a career full of twists and turns.

She wrote for the magazine Műértő [lit. 'Art Connoisseur'], worked as an art insurance broker and then as an interior designer who reimagined antiques, and designed vintage clothing for a Hungarian woman's shop in Vienna. In the 2000s, she worked as a creative consultant for Praktika magazine, where she had the opportunity to try her hand at the role of a stylist.

She also worked in the art trade: "You had to talk the client's ear off. The art trade was quite a comfortable world back in the '80s. But then that world changed as well, and change has always inspired me to do the same. However, even into my forties and I didn't know which direction to go in. I had always followed the path that my immediate family and friends from childhood would steer me down. Fortunately, my husband was always very supportive."

Her daughters were born in the '90s, right around the time that Hungary's childcare assistance program was being restructured. As a result, she was able to stay at home with them for six years – a period that she remembers quite fondly. "I was incredibly lucky to have been able to indulge in this." Because of her husband's job, the family moved to Sopron for a few years. These few years turned into 10, and Kati had to adapt again.

"Relocating and adapting: in the end, that's what my life has been about."

The family then moved back to Budapest. By the time her husband got a job in Denmark, their kids had grown up, and Kati decided that from then on, she was going to cater to her own needs rather than to others'. That was 10 years ago. Since then the couple has been living in a long-distance relationship, with Kati's husband traveling back and forth between the two countries. They manage to see each other roughly once every two weeks.

"I've had to surrender my own life for many years," Kati reflects while sipping on a lemonade in her home amidst her imaginatively and tastefully repurposed belongings. "At such times, you just have to accept the situations you find yourself in." Then a friend pointed out to her that she was living in a cage. "My friend was right. In cases like this people start to feel down. They become embittered – often ill." She believes that being in a cushy situation financially doesn't help when you're penned in (of course, it doesn't hurt either). Nor does it solve anything when parents keep telling their children for years that they are in a privileged position. “When someone really wants to do something but is not allowed to, they often end up becoming ill. And I realized that I wanted to be visible in my life and in the lives of others.”

So Kati opted for a kind of adaptation that was not typical for her – and it is not at all unlikely that this was what kicked off the trajectory of her career. "It's a great living situation: I get to manage my time the way I like. I love it when my husband comes back and when I see my grandchildren, but I don't feel as though I were just a grandmother." Her unconventional look alone gives the impression of anything but a grandmother. And babysitting for her grandchildren 24/7 is out of the question as they live thousands of kilometers away in Thailand, although she often gets the chance to see her other daughter, who works as a physiotherapist in Budapest.

Kati has gradually built up her portfolio as a personal stylist, and as a wardrobe designer she has been tidying up her clients' armoires. "At first, I only looked at women's clothing in terms of function and practicality. But then I realized the extent to which the past plays a role here as well. Clothes are constantly changing, as is true with people. When you get stuck in a rut, it restricts you both psychologically and mentally. I'm only able to analyze the present, but when I start to dissect these hang-ups, the past often begins to come up, which is something that can really make people miserable," said Kati, reflecting on the psychological side of her work.

Today, Kati is officially retired. She stepped down from her company, but it's possible that she's been operating at an even higher RPM since then. She is motivated by education and imparting perspective. Starting this fall, she will teach in the personal stylist program at the Krea Design School. On top of this, she will also be leading the stylist program at the Budapest Fashion School. Next spring will see the launch of a personal stylist course under her supervision at the Éva Fábián Makeup Academy, and she will also give lectures at the Werk Academy.

She has plans to develop a downloadable PDF guide for anyone who wants to analyze their wardrobe on their own. She also makes inexpensive yet imaginative jewelry and reworks garments – a portion of which she presented to us at her home – mostly by pairing old, discarded, or unusual pieces. In the past, she made textile pictures from discarded materials.

Most of the new skills she has picked up after university have been self-taught. She was just as eager to immerse herself in psychology as she was to learn about computers and her latest skill, making Instagram videos. "If I'm interested in something, I'll download everything about it from the web and read it. If the need arose, I'd fix the lights, refurbish furniture, sew clothes – even if I didn't know what I was doing. I think what deters a lot of people from doing a bunch of things is that voice: 'Oh, I'm not even gonna try because I don't know anything about it.'

And yet, it's when we leave our comfort zone that we start to encounter the interesting stuff."

The way she sees it, people in their fifties and sixties in Hungary are too scared to change anyway, let alone anyone older. This could be due to many things, but she's convinced that one of the reasons is the fact that the entrepreneurial mindset has never been a part of people's upbringing and culture in Hungary. "I realized that if you stick to what's familiar – an environment where you know everyone – and you're afraid of change, you may as well get pickled, jarred, and given your pension check."

And it wasn't just when she was choosing a career that Kati steered clear of a jarred-up lifestyle – she's been doing so ever since. Kati regularly goes to self-awareness groups, where most participants are between 40 and 65 years old – and she is the oldest. "Even in your eighties, you still have problems to solve, problems worth tackling," she says, explaining the lifelong benefits of such groups.

And when it comes to the passage of time, Kati has a different attitude than most people: "It's such a good feeling to get over certain things – you're casting off a bunch of weight, and it's so liberating," she says. Perhaps it is the combined effect of everything mentioned above that she is not the sickly type (then again, other factors could also be at play). On the contrary, she sees a very bright future and promising career ahead of her: "I think it won't be until my eighties or nineties that I really make a name for myself as well," she said, referring to Picasso's muse, Françoise Gilot, who didn't peak professionally until the age of eighty. "Of course, that's assuming that we can keep the peace and sustain the world until then."

The translation of this article was made possible by our cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.