The news that a bust of the man who was Hungary's regent between the two world wars and throughout World War II was unveiled in an office within the Hungarian Parliament caused quite a stir recently. The autocratic leader remains a deeply polarising figure in Hungary to this day, and there are still things that are not widely known about him.

Translation by Allen Benjámin Zoltán.

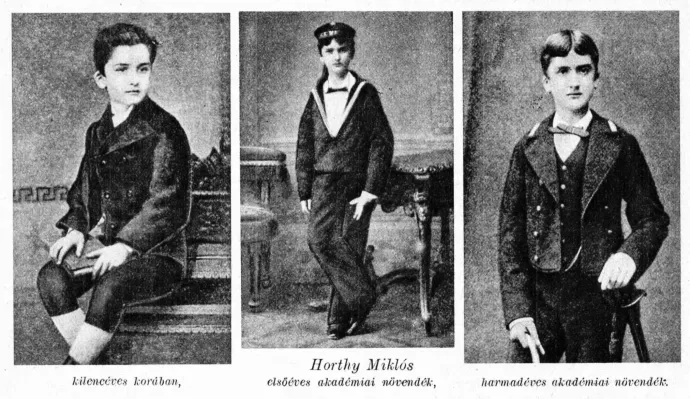

The first thing that comes to mind when people think of Miklós Horthy, Hungary’s third and last regent, is him entering Budapest on his white horse. Even though his person has since become controversial (especially due to his politics and his responsibility in the “white terror” of 1919 and in the deportation of Jews), it is indisputable that his strongman politics had garnered a cult following already during his lifetime. That is, he was seen as a man who lived only for his country, who conducted himself as was expected from the Christian-conservative culture of the time. Yet it was not always so:

“Horthy’s cult can be understood as a reaction to the country’s collapse during the First World War. After the traumas of the collapse, the Hungarian Soviet Republic, and the Romanian occupation, many right wing radicals tried to paint a picture of Horthy – who was commander of the National Army – as someone society can draw strength from, and who will heal the wounds suffered by the nation.”

– writes historian Dávid Turbucz.

According to Turbucz, this type of communication recalled the times before 1918, because they started portraying the regent as a ruler. The signs of this can be clearly seen as early as the mid-1920’s on anniversaries of events connected to Horthy, and from reports concerning his diplomatic visits abroad. As time went on, his political activity and power increased, and his personality cult was transformed. They began referring to him as the “Father of the Nation” and celebrated him as the manifestation of Hungarian-ness, which was closely connected to irredentism.

His personality cult is reflected in the fact that in those years there used to be a Miklós Horthy square (now named after Zsigmond Móricz) and a Miklós Horthy bridge (now called Petőfi bridge) in Budapest, and that a series of grand celebratory events were organized on his birthday every year. Furthermore, the laws in place at the time protected his person; one could be heavily fined for insulting the regent. The press was not exempt from this either, as the papers Ujság and Népszava were penalized for criticizing him.

These strict rules affected common people as well, take for example this extract of a Népszava article from 1924: “Last December, day-laborer József Tóth was having a drink in one of the pubs on Lenkei street. At the table next to him, some policemen were drinking wine and singing the so-called “Horthy-march”. Tóth apparently remarked that he does not like hearing that tune and asked them not to celebrate Horthy in his presence. He was prosecuted for insulting the regent and was recently sentenced to two months in prison and fined 100,000 crowns by the Törkey-committee.”

Okay, but what was Horthy’s life like before he rode into the regent’s office at the age of 52? According to his autobiography, it was not a life that a PR expert of his time would have dreamt of.

The adventures of a young cadet

Horthy’s recollections paint his young self as someone who did not like to study but appreciated a cheeky prank and was allured by adventure and the unknown, dreaming of one day traveling the world. In those days, the most straightforward way of achieving those dreams was by joining the navy. His enthusiasm for a career as a naval officer was not shared by his parents however, as his brother, four years his senior, had died from sepsis after some ammunition exploded near him while he was a novice at the Rijeka Naval Academy.

Horthy was therefore grateful to his mother for persuading his father to support his journey to the Naval Academy. After becoming an officer, the young Horthy made a point of enjoying the perks of his position. He not only took pleasure in the voyages that took him to faraway lands, but the times off – that is, in the night life of the docks as well. He relished these moments so much that once he even disobeyed orders for the sake of partying. In fact, his defying of orders was a result of him having defied orders.

The story begins in Barcelona on a ship named Radetzky. Notable people were also allowed on board at times with a few restrictions, and were to be toured around by the cadets, including Horthy. The visitors were allowed to stay until 5 p.m., but Horthy made an exception for a family who arrived quite late. He was punished for this with being confined to the boat for two weeks. At least he was supposed to be, as he quickly donned civilian clothes and went to the docks in hope of finding his friends at a nearby nightclub.

Surprisingly, his higher-up who had ordered his punishment, appeared at the docks as well. To remain unnoticed, Horthy raised his napkin to his face and vanished into a side-street, from which he snuck onto the same higher-up’s boat and returned to the ship. The moment his superior boarded the Radetzky, he summoned Horthy to the dining room, who appeared in his cadet uniform, looking sleepy, having masked any trace of misbehavior. According to Horthy, his higher-up was

“so taken aback that he dismissed me instantly”.

He was not always this lucky though, as another Barcelona adventure did not end quite as he intended. Horthy met a group of Dutch sailors at a naval exhibition, and after a few nights together they invited him to an unusual dinner on their ship.

The point of the event was to gather cadets and pit them against each other in a drinking contest, each representing their team and their nation. It was Horthy’s turn that night. Although the feast began at 6, he described the drunken “corpses” being dragged away as early as 9 o’clock.

Those who could not keep up were put in dinghies and were taken to a ship. If they were lucky enough, their own. Most however, were not so lucky, including Horthy. Although he “held on for long”, he could not escape his destiny, and woke aboard a foreign ship the next day.

“The next day I woke up in a tidy cabin. I rang the bell, and a sailor who was not wearing a hat appeared. I did not understand a word of what he said. It was only on the deck that I realized I had spent the night on a Russian corvette [a small warship]. Boats sailed to-and-fro between the ships all morning, exchanging cadets delivered to foreign ships.”

– the future inviolable regent wrote.

Sources:

- Miklós Horthy: Emlékirataim. Buenos Aires, 1953

- Dávid Turbucz: Horthy Miklós. Napvilág press, Budapest, 2011.

- Dávid Turbucz: A Horthy-kultusz 1919-1944. http://disszertacio.uni-eszterhazy.hu/7/2/Turbucz_David_tezis.PDF

- Dávid Turbucz: A Horthy kultusz kezdetei. https://www.epa.hu/00900/00995/00020/pdf/turbuczd09-4.pdf

If you enjoyed this article, and want to make sure you don't miss similar ones in the future, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!

The translation of this article was made possible by our cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.