"An uninhabited land, no indigenous people to be seen; a barren, rocky landscape and bears with white fur that have heretofore never been seen."

– thus was written in the notes of the humanist scholar Stephanus Parmenius Budeius, the first (or perhaps second, but we'll come back to that later) Hungarian to reach the Americas aboard an English ship in 1583. Why the uncertainty? Because a Hungarian man by the name of Tyrker may have reached the North American coastline with the Vikings as early as circa 1000 AD. In fact, if the sources are to be believed, he was also the first Hungarian to become intoxicated by the grapes growing there.

But just who exactly was this depicter of polar bears, Parmenius Budeius, or this grazer of grapes, Tyrker: individuals who reached the new continent long before colonial times?

Although the discovery of the Americas is traditionally dated to 1492, several sources suggest that Viking ships may have landed on the North American coast as early as around 1000 AD. And one of these vessels may have even had a Hungarian on board.

He was known as Tyrker, and according to Viking chronicles, he boarded a ship under the command of Leif Erikson in Greenland (a land that had been explored by Leif's father, Erik the Red). From there, they followed the coast of the island to the northwest and then westwards, crossing the present-day Davis Strait to reach the shores of what is now Canada's Newfoundland and Nova Scotia as well as the coastal region where Boston would be later founded.

Tyrker is regarded as a good friend – even adoptive father – of Leif's father in the Heimskringla, an Icelandic collection of Viking chronicles that was translated into English by the Scottish historian Samuel Laing. This work was used as a source by Hungarian-American historian Jenő Pivány in his 1909 study of Tyrker.

How did a Hungarian end up among the Vikings?

This question was also of interest to Pivány, who, examining the works of contemporary historians, discovered several pieces of evidence in the chronicle indicating Tyrker's Hungarian heritage.*

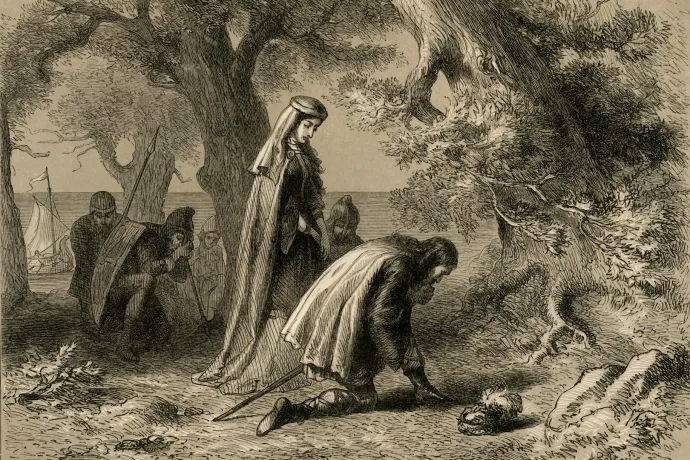

It appears that upon arrival in Newfoundland, Leif decided to weather the winter there. So he divided his crew into two parties and sent one of them out to explore. Tyrker did not come back after a while, so they set out to find him. Eventually, they found him in a patch of grapevines, where he was reported to be acting strangely, rolling his eyes, making faces, and when asked questions, answering in his native language. The vikings, of course, didn't understand him, so Tyrker described the vines he found not far from their campsite in Old Norse.

"Do you tell the truth, my fosterer – are you certain?" Leif cried out according to the account, to which Tyrker replied, "Rest assured, I speak the truth, for in my homeland, grapes grow in abundance." Of course, it's strange that Tyrker would be drunk on grapes, given that, as is well known, they only produce an intoxicating effect after fermentation.

Tyrker's ability to identify the grapes, together with the fact that he is described as having a body structure similar to that of the Hungarians of the 9th century, may serve to strengthen the speculation of his Hungarian origin. The sources mention him as having a small stature, clearly distinguishing him from the characteristically tall Vikings.

Was he Hungarian or not?

At the same time, however, several historians do not describe Tyrker as Hungarian but as being of another ethnicity. In the chronicle, he is referred to as Turkish, while the Danish historian Johannes Brandsted suggests that he may have been of Germanic origin. He and German author Rudolf Pörtner, author of the historical work The Vikings: Rise and Fall of the Norse Sea Kings, believe that Tyrker may have either come into contact with the Scandinavian peoples as a warrior or that he took the Turkic-sounding name during battle with the Turks, which was then used by his viking companions.

Although Pivány does not explicitly claim that Tyrker is of Hungarian origin, he says there are several arguments supporting this idea. The fact that his name sounds Turkish does not necessarily mean that he was one, since Byzantine sources referred to all peoples of the steppe whose way of life and political structure were similar to that of the Turks as Turks – even the Hungarians.

According to the chronicle, when Tyrker spoke in his native tongue, the vikings couldn't understand him. However, had he been of Germanic origin, the vikings would presumably have recognized it immediately, since they had a special term for the German language (saxneskr, i.e. Saxon, whereas the language spoken by Tyrker is referred to as thyrsk in the chronicle).

Of course, this begs the question: if he truly was Hungarian, how did he come into contact with the northern Scandinavian peoples? To explain this, Pivány points to the merchant lifestyle of the Vikings. The Norse had settlements and trading posts not only in Greenland and Iceland but also in several parts of Europe. For example, they had a military depot near the Principality of Kyiv (which bordered the former Kingdom of Hungary) along the lower portion of the Dnieper River where they traded slaves, among other things. It is possible that Tyrker was one of the slaves who ended up in the Scandinavian territory, but it is also possible that he joined up with the vikings as a warrior.

For this reason, Pivány considers it possible that he is either of Hungarian or Turkish origin, and although he has presented evidence in support of Hungarian, it has yet to be conclusively substantiated. Hence the importance of the other Hungarian mentioned earlier, Stephanus Parmenius Budeius: records attest to his Hungarian background and the fact that he took part in an expedition to the New World in the 16th century.

Two weeks in the New World: the fatal journey of Stephanus Parmenius Budaeus

A celebrated humanist poet and scholar of his time, Budai Parmenius István was known to the outside world as Stephanus Parmenius Budaeus. An essay published in 1985 revealed that Parmenius' studies in Hungary eventually led him to Western Europe and later to England, as was the custom of the time. It was at Oxford that he met Richard Hakluyt, a humanist scholar and geographer, who in turn introduced Parmenius to the inner circle of Sir Humphrey Gilbert, one of Queen Elizabeth's favorite knights. He was invited to join Gilbert's expedition to Newfoundland in June 1583.

After 52 days at sea, the four boats carrying the crew landed in St. John Bay, Newfoundland. On the third day following the expedition's touchdown, Parmenius wrote his account of the passage and his first impressions. Soon afterward, Gilbert declared the island a colony of the Queen, from which they set sail for home two weeks later. On the 29th of August, however, the ships were caught in a storm and the flagship Delight, which Parmenius was a passenger of, struck a rocky reef, tipped sideways, and sank beneath the waves

The disaster's only survivor was the captain, Edward Hayes, who later recalled Parmenius in his report to Queen Elizabeth: "Amongst whom was drowned a learned man, a Hungarian, born in the city of Buda, called thereof Budaeus, who, of piety and zeal to good attempts, adventured in this action, minding to record in the Latin tongue the gests and things worthy of remembrance, happening in this discovery, to the honour of our nation, the same being adorned with the eloquent style of this orator and rare poet of our time."

The translation of this article was made possible by our cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Sources:

- Jenő Pivány: Was Tyrker from the Heimskringla Hungarian? Századok, 1909.

- Gáborné Havas. Medieval Hungarian travelers. Geographical Museum Studies, No 1, 1985.

- Péter Árpád Harmat: Who were the Vikings?

- Antal Szöllősi: History of the Hungarians in Norway