Translation by Allen Benjámin Zoltán.

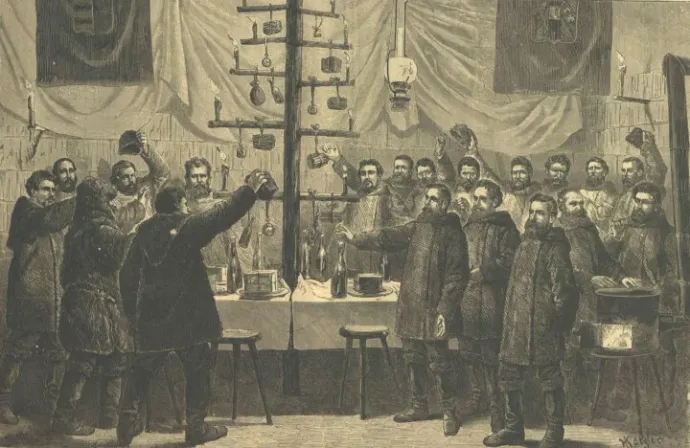

On Christmas Eve in 1873, somewhere beyond the 80th degree of northern latitude, deep in the Arctic, a peculiar festivity was being held. The sailors, dressed in their very best, filled the igloo which they had been working on for days before the celebration. The walls were covered with colorful flags and a long table was set with a white tablecloth, topped with an installation wanting to resemble a Christmas tree. The tree was crudely thrown together from sticks and decorated with colored paper, but to the sailors, even this was a heartwarming sight. Gyula Kepes, the ship’s surgeon recalled this in an edition of the Sunday Newspaper (Vasárnapi Ujság) towards the end of 1874, touching on what was on and what was under the tree:

“The gifts given by the kindhearted women of Vienna and Pula for this exact purpose hung on these dry branches: boxes filled with 50 cigars apiece, all sorts of sausages and chocolates. Around the tree were 18 plates filled with ham and freshly baked bread and beside those, even more presents: meerschaum pipes, cigar holders, pocket watches, wallets with a few silvers inside and flasks filled with pálinka, (TN: a type of brandy popular in Hungary) the latter of which was accepted as a most wonderful festive gift by the sailors.”

Considering the circumstances, the celebration was lavish: the 24-man crew feasted, raffled the presents, and even the officers partook in the festivities before returning to their cabin for their private party. But the night did not go by without a nagging sense of uncertainty: it had been one-and-a-half years since the 24 men became stranded in the arctic after their ship, The Tegetthoff got stuck, frozen in ice. They drifted along with the ice into uncharted territories, and by the end of that year, the fact that the ship would not last another year was an ever-recurring topic of conversation.

In search of the passageway

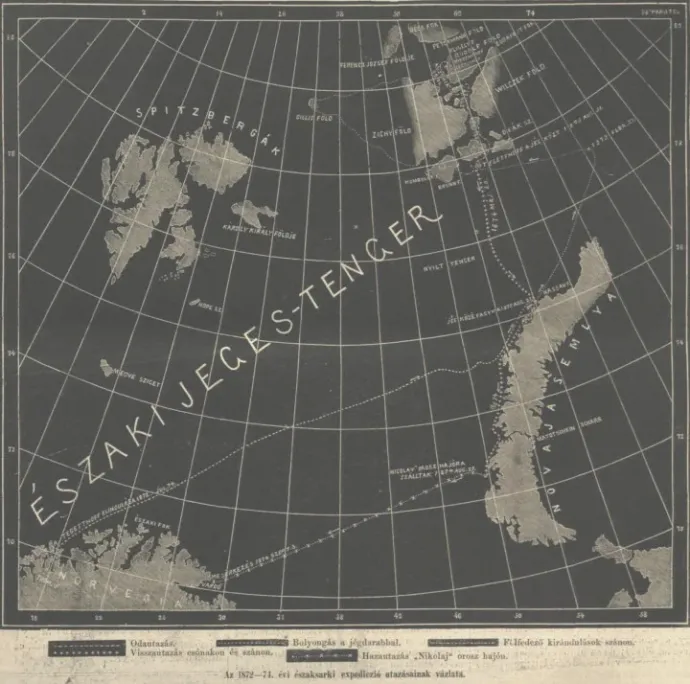

It was 150 years ago that The Tegetthoff set sail from the Norwegian city of Tromsø on 14 July,1872. The story of the expedition begins much earlier, however. The adventure itself started the day before, when The Tegetthoff began its journey to Norway from Bremen where it had been built especially for the occasion. But the two leaders of the expedition – commander Karl Weyprecht and lead scholar Julius von Payer – had been exploring the waters above Norway in a rented sailboat since 1871 in order to assess the conditions in the Arctic.

Weyprecht and Payer both volunteered for the journey, they were both part of the Austro-Hungarian army. Furthermore, the Austro-Hungarian ministry of war supported the expedition, which was practically a military operation, even though on paper, it was funded by the private donations of aristocrats and the nobility. The objective was to find the Northeast passage, which was yet undiscovered. The passage would connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans via a route above Asia which would only be passable during the warmer months and was hoped to be of great economic benefit for the Monarchy. The other goal of the expedition was to explore the North Pole.

Although the crew was from all over the Monarchy, Weyprecht and the officers were mostly German, or had connections to the region. Only one Hungarian, the aforementioned Gyula Kepes, was onboard The Tegetthoff. This reflected the amount of Hungarian funding: only 7.5 thousand of the approximately 222.6 thousand forint budget was covered by Hungarian donations.

On land and on ice

The expedition was going as planned until The Tegetthoff, which operated both as a steamboat and a sailboat, left Tromsø, and reached Novaya Zemlya, a northern archipelago belonging to Russia, in just a month. There they met Count Johann Wilczek, one of the expedition’s biggest sponsors, who himself invested 40 thousand forints in the venture. He had arrived just before them and left a shipment of food for them at the northern end of the archipelago. They said their goodbyes on the 21st of August 1872, and The Tegetthoff continued its journey northward.

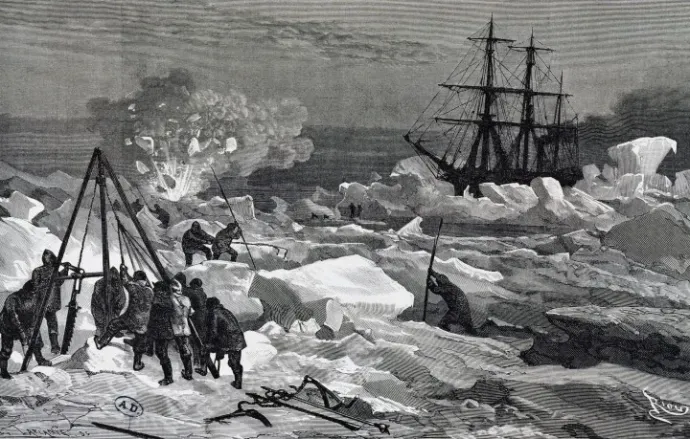

Later that day, the ship got caught in an ice barrier and froze into it. From then on, the Tegetthoff and its crew could do nothing but drift along with the tides.

In the following months, tension grew as it appeared as if mother nature was directing a horror film. The ice around the ship kept getting thicker, with sheets of ice pressing against the hull and, after a while, even reaching above deck level. The crew soon had to learn about a phenomenon called ice pressure. This intense force is generated as the ice sheets move and stack on top of each other. And if it pushes in the direction of the ship, it can easily damage the vessel. During the months they were drifting, there were multiple times when the crew had to evacuate the ship in fear of it giving in any minute.

But that was not all: everything from lard to the mercury in their thermometers was frozen, and mice on board did not seem to mind the freezing temperatures. They reproduced and feasted on the crew’s scarce food reserves. The sailors' mental health also deteriorated, as the sun set for the winter in the Arctic, leaving them in permanent darkness. But they kept busy by teaching the illiterate how to read, shooting practice, and hunting for polar bears and seals, which went surprisingly well.

The ship first drifted northeast, then the changing wind took them northwest. The crew tried to free the ship many times, but without luck. After a year of drifting, on the 20th of August 1873, the unexpected happened: they saw land. It was an until then unknown archipelago which they quickly named after the emperor. Gyula Kepes recalled in the 1874 edition of the Geographical Notice (Földrajzi Közlemények):

“Everyone runs to the deck to look at the impossible; the poor men can hardly recognize it! They haven’t seen such a thing for the past year, and even if they had, the cold, aggressive oceans and the scrunching of the ship would’ve erased it from their memory. The moment we could finally baptize new lands approached. And as with every baptism, wine must play a part, and so it must play a part here too. Thus, the officers and the crewmen appear with glasses in their hands, and with the chant “Hurrah!” sounds thrice. The known world has now grown with the addition of “Emperor Franz Josef Land” to its horizons.”

Escape into victory

Another winter forced them to pause their exploration of these new lands, but as soon as they could, they started mapping the archipelago. They named many islands and straits, like Wiczek Land, Zichy Land, Austria Strait and Pest Cape (renamed Budapest Cape at their return home as Pest and Buda united in 1873 while they were away).

After the Christmas celebration mentioned above, the officers started wondering how to get home. By the beginning of 1874, it was obvious that the capsized Tegetthoff was not going to survive a long journey. And though Kepes, the surgeon, did exemplary work according to the crew, many were sick. In May of 1874, the ship’s mechanic, Otto Krisch, died of pulmonary disease. They buried him on Wilczek Land, and they started their somber trip back home; they left The Tegetthoff. They pulled two sleighs filled with food and the most important equipment, and the ship’s three boats, going southward. Their plan was to walk and sail until they reached Novaya Zemlya.

That they managed to do it is a fine example of human endurance: after three months and hundreds of kilometers of travel they faintly saw the northern end of Novaya Zemlya. They continued their journey by boat, to where Count Wilczek had stashed some food for them, but were taken off course by the tides. They had hardly any food left when they crossed paths with a Russian whale-hunting ship on the 24th of August 1874. The ship helped the 23 starving men and took them to the Norwegian town of Vardø. From there on it was smooth sailing, and the 812-day long expedition came to a close.

Though the expedition did not find the passageway, they were mostly celebrated as heroes, and the officers were given many medals and fancy functions. Their contemporary, Eduard Strauss, even wrote a Weyprech-Payer March commemorating their efforts:

But there were critics as well: the Catholic-conservative press of Vienna did not approve of the hype around their return, and the Prague-based Politik considered the expedition an unscientific farce. In truth, apart from a few lands with Hungarian names, not much was really achieved: the Monarchy never managed to make a rightful claim to Franz Josef Land, and it was later annexed by the Soviets. The archipelago remains part of Russia to this day, and its economic benefits are not to be underestimated either, as it is surrounded by oil-rich waters.