'We've gone back to the 16th century. Only it's not our fault' – a report from Kyiv, left without power and heating in the bitter cold

"We can usually heat the apartment to seven degrees Celsius, sometimes eight. Our best result so far has been 8.8 degrees, and the lowest was four."

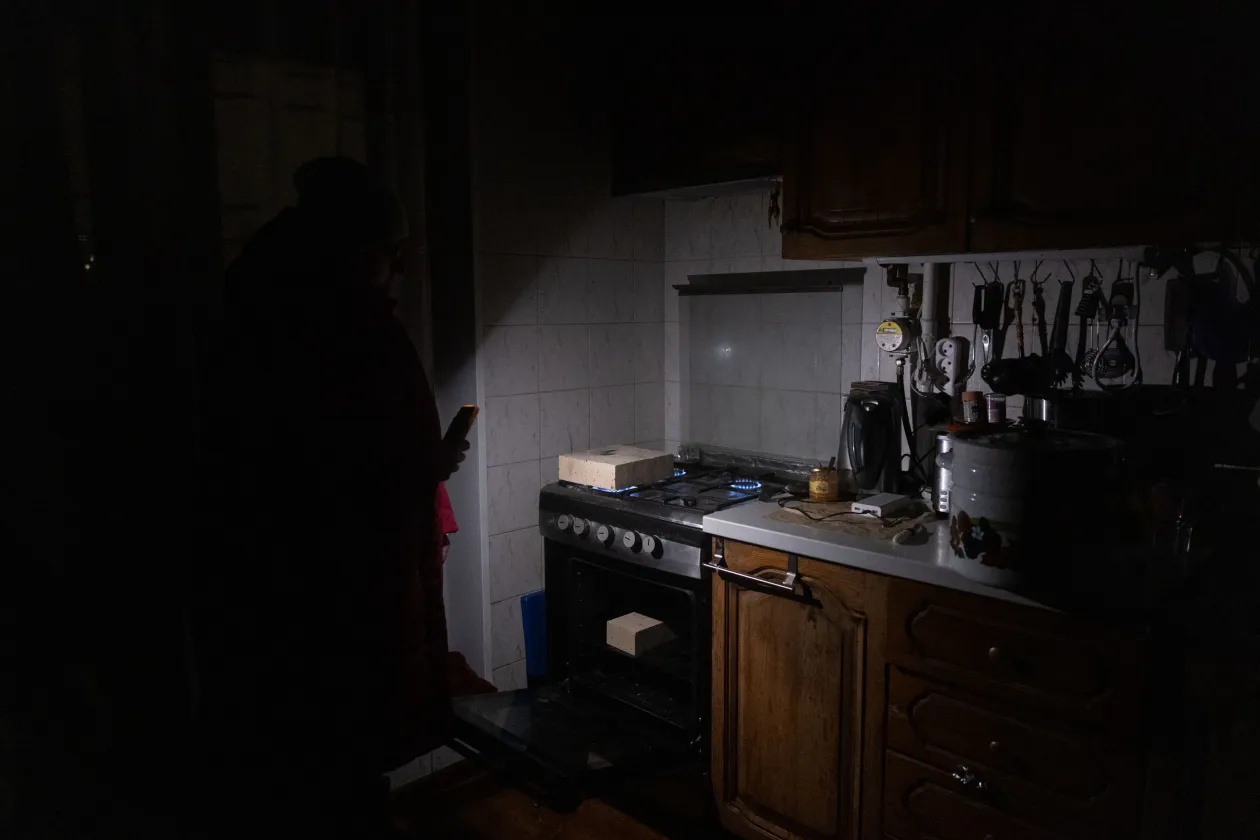

Rusanivka, an artificial island built on the left bank of the Dnipro River in Kyiv, was developed in the 1960s. Viktoria and her husband, Konstantin, live in one of its typical 16-storey buildings. Like most residents of the capital, they have been living without heating since January 9, more than two weeks ago. Viktoria gave us a tour of the darkened apartment, lighting our path with her phone: half-wet pants were hanging on the door – under these conditions, it takes a week to a week and a half for the clothes to dry, she said.

Standing next to the bed in the bedroom, she pointed to a structure made of bricks: in the evenings, they heat the room by lighting a portable gas cylinder used for camping, positioned underneath it and in the kitchen they use the gas stove for heating. If all goes well, they manage to heat the two rooms to 1.5 degrees Celsius at this time of year. If they are at home more and have time to keep the heat on, the temperature can even climb up to 2 degrees higher than that. While she talks, she leads me to the window: it is so cold here that the condensation has slowly solidified into ice, sticking the bottom of the curtain to the window sill.

She explains that they try to stay active from morning to night. Heating the apartment takes up a lot of time and they also go down to the crisis shelter next to their building to charge their phones and warm up, while also trying to help their elderly neighbors in the building. Under these circumstances, she isn't able to go to work: if she were to commute, she wouldn't have time to keep the apartment warm. “I'm very worried about the radiator: if the water freezes, the pipe could burst, so it's very important that the apartment doesn't cool down completely. We can't leave, so I feel like I'm in prison – a prisoner in my own home. But we are not hopeless. We are strong, we can organize ourselves enough to cope with the situation. We are doing what we can, to the best of our ability.”

Kyiv is experiencing its most difficult winter since the first year of the Russian-Ukrainian war, which has now spread across all of Ukraine. Repeated Russian attacks have plunged much of the capital into an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. The three winters that have passed since February 2022 have been the warmest in Ukraine in the last 150 years, but this year is completely different. Temperatures in Kyiv have been below freezing since the end of December, and in mid-January they remained below -10 degrees Celsius, which Russia has taken advantage of with several large-scale attacks. In January, Moscow struck the capital's energy infrastructure four times with such force that nowadays it is less surprising when someone has no electricity, heating, or water than when they do. In the bitter cold, those who "only" lost power days or weeks ago are considered particularly lucky.

The latest Russian strike of this kind took place on Saturday morning. According to Ukrenergo, which operates the national power grid, 80 percent of Ukraine had to prepare for emergency power outages on Saturday. The windows where some light can be seen belong to apartments which have either had their power temporarily restored or are using battery-powered lighting. The mayor of Kyiv, Vitali Klitschko wrote on Telegram that half of the capital's 12,000 residential buildings were left without heating after Saturday’s attack, even though the day before, the number of buildings without heating had been reduced to less than 2,000.

Over the past few weeks, there has hardly been a neighborhood in Kyiv that has not been affected. We visited several neighborhoods on January 21 and 22, and the accounts of all the locals we spoke with had one thing in common: they did not complain. Those who only lost power consider themselves lucky to still have heating, while those who have no heating but good insulation, emphasize how fortunate they are compared to those whose homes have completely frozen over. With their apartment at 4-8 degrees Celsius, Viktoria and her family are among the worst off in the neighborhood, but there are others who have had an even harder time over the past few days. On Tuesday, a drone crashed into the building next to Viktoria's, breaking the windows of dozens of apartments. The residents are now trying to prevent their apartments from completely freezing in the minus 9-10 degrees Celsius weather by using boards, blankets, and insulating foil.

"We've gone back to the 16th century," a man on the ground floor says. “Only it's not our fault.”

"Our apartment doesn't get very cold because we had our windows replaced a few years ago. We are lucky that way," an elderly man on the ground floor of the building next to Viktoria's tells us, while Helena, the building's attendant watches us from her seat, with only a single candle providing light. Several windows in Vitali's building, who works as a chemist, broke during Tuesday's drone attack, but he believes that they survived it thanks to their new windows and doors. "This building was constructed in 1969, and many people still have the same Soviet-style windows that were put in back then because they don't have the money to replace them. It is very cold in those apartments now," he said.

His building has been without electricity for ten days, except for a few hours a day, when they heat with electric radiators and are able to keep the apartment at around 16-17 degrees Celsius. "There is no solution to this situation. I go to work at the institute and try to continue my research. There is electricity, heating, and water there, but that is a rarity in Kyiv today."

45-year old Katerina used to live in Luhansk, but fled to Kyiv in 2014 to escape the Russian occupation. The heating and electricity in her apartment in Rusanivka have been sporadic since January 9, and for the past three days, she has had neither, so she is temporarily sleeping at her relatives' house.

"When you're alone at home in the cold, without light or heating, everything can become frightening, and you may get anxious or even panic, she said. "But then I go outside and see elderly people climbing the stairs in the dark because the elevator isn't working due to the power outage, and I see parents trying to take care of their young children. That gives me strength. Seeing how others are coping with the situation helps me to cope with it too, and reminds me that I'm not the one in the most difficult situation. I still think Kyiv is the best place on earth – especially when there's no electricity, heating or internet."

Vadim lives on the same street. We walked up to the seventh floor of the 16-story building with him. He also considers himself, his wife, and his five-year-old daughter to be among the lucky ones: the building's insulation was completely renovated a few years ago as part of a government program, so their apartment doesn't get cold, and the temperature usually stays between 18 and 20 degrees Celsius. On the day we visited, it was 15 degrees.

His parents live in the building across the street, he tells us in the kitchen. They had no electricity for five days, but now they do; at Vadim's place, it's the opposite: they had power until two days ago, but then it went out, and now it comes back for just an hour or two every day. "The buildings in the neighborhood look like a chessboard these days," he said, looking out the window. “One has light, the other one doesn't.”

The Russians want to scare us, demoralize us, he said, while his wife Irina made us tea. But the Russians don't understand us, we don’t scare easily. The Ukrainian people are brave, they don't care what Russia does. We will hold out for a long time, even in the most difficult situations. The current situation is grim, but we will defend our homeland. We have no other choice." Vadim is a manager at a Kyiv-based company. He tells us about how he helped evacuate people from the Kyiv area in 2022, rescuing dozens of people from Bucha, one of the sites of the Russian massacre with his car.

The tea had just cooled to a drinkable temperature when the power suddenly came back on, flooding the whole apartment with light. We went into the living room so he could show us his curved gaming monitor in action – he was clearly proud of it – then he typed something into YouTube and split his screen in two. A fireplace appeared on the screen of the living room TV and his little girl, who had been jumping on the bed, climbed down and knelt in front of the TV to watch the flames.

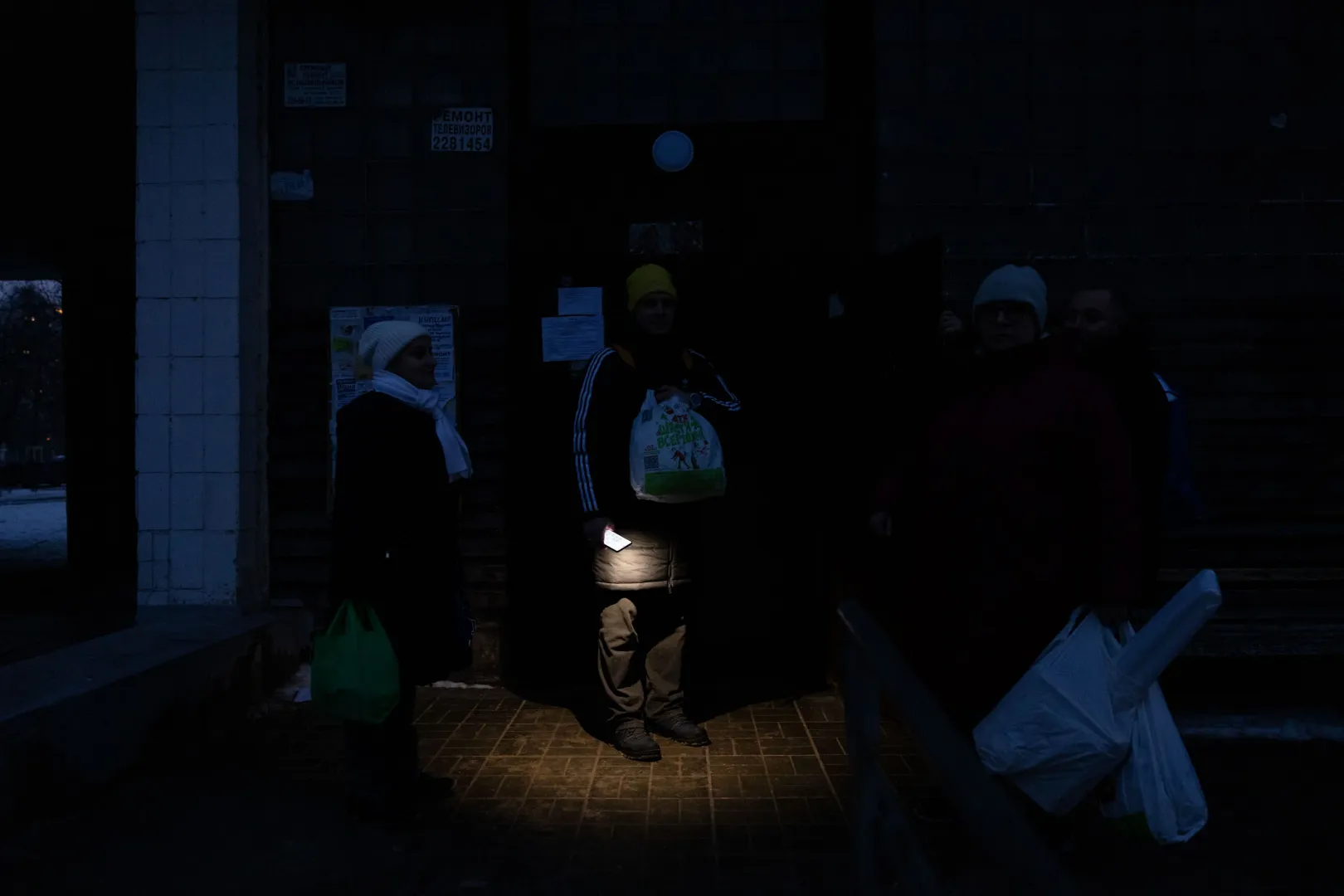

Over the past four years, everyone in Kyiv has learned where the nearest shelters are located in relation to their homes, and most people now know where they can go to warm up, charge their phones, and drink hot tea when their homes are cold and without electricity. The crisis points, known as "points of invincibility," are often schools, kindergartens, and municipal buildings, but—especially in the vicinity of housing estates—disaster relief tents heated by generators have been set up as well.

The ambiance and furnishings of the tents vary greatly, but they do have a few things in common: warm temperatures, power outlets, children's corners, and the fact that as soon as you enter, you are handed a cup of tea. In the downtown park named after the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko, a tent reminiscent of a Kazakh yurt was set up as a crisis point: in addition to tea, we were offered baursak (Kazakh doughnuts), while a man was lighting a fire in front of the tent to heat oil for the next batch. In one section of the yurt, local pensioners were charging their phones, with the TV running in the background. There were about fifteen books, mostly about Kazakhstan, lying on one of the chairs, while on the other side, a small exhibition had been set up about Kazakh folk costumes and folk motifs.

We met Sasha, a young journalist, in one of the tents in Rusanivka, sitting in front of her laptop in a coat. "Two days ago you couldn't even sit down, the tent was so full, all the chargers were being used, probably because of the latest drone attack," she said. The temperature in her apartment is now 5 degrees Celsius, which is one of the reasons she goes to the crisis point, as well as for the internet. When there is an air raid, people are evacuated from the tent, but apart from such periods, this is where she has been working from lately.

The girl is from Zaporizhzhia, her parents still live there, and her grandparents are only ten kilometers from the front line. "If all this were happening in the summer, it would be easier. It's very cold, and that affects our mental health: people are more tense, they get upset more easily, even here in the tent." Almost everyone passing by had a ten-liter canister or two with them. They carried these to the water distribution point across the street, surrounded by the hum of generators providing power for shops and cafes.

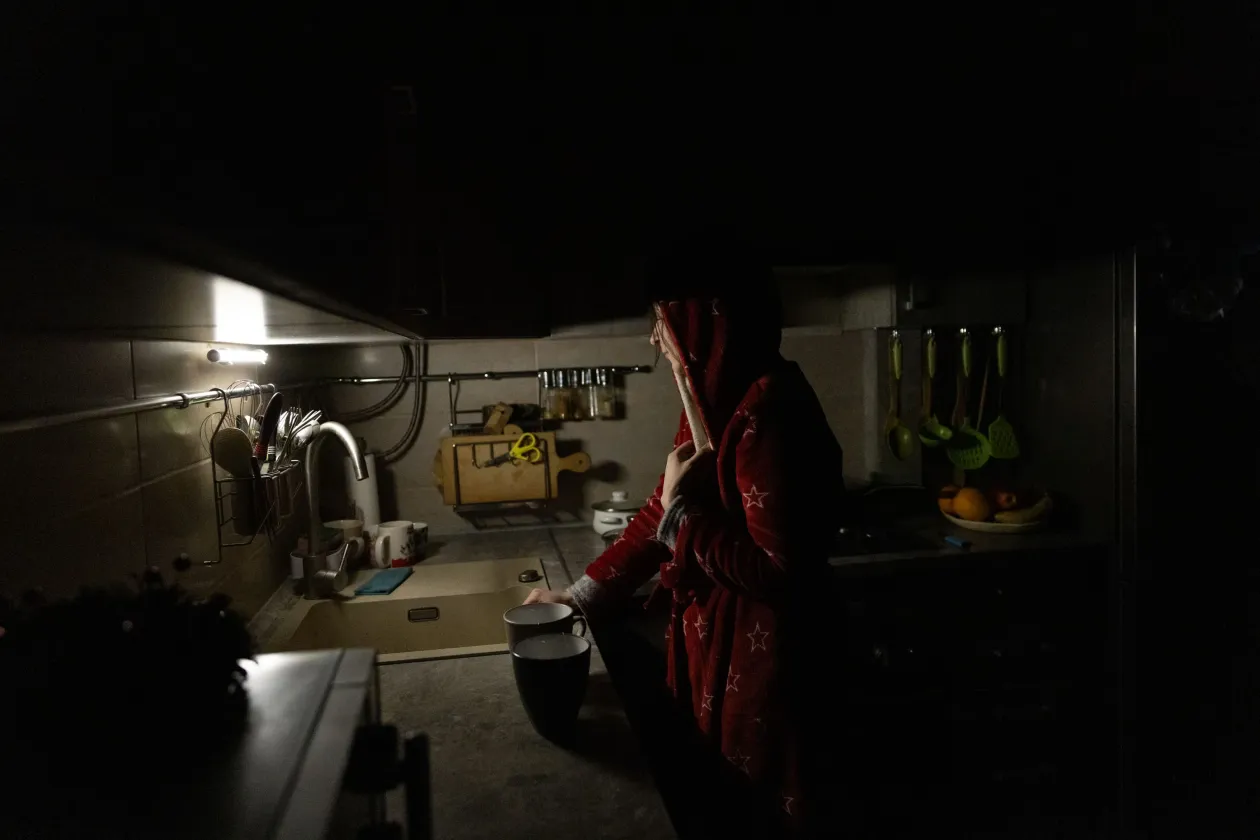

Margarita attends university in Kyiv, she is majoring in philology, English, and Italian. She finished her last exam of the semester a few days ago—she took it online because there is no heating at the university—and it was during our visit that she first came to one of the crisis tents in the Bereznyiak district to read. “Our apartment is around 16 degrees Celsius. We do everything we can to keep it as warm as possible: we sleep hugging hot water bottles, we warm up clothes for our cat using these bottles, we bake in the oven and cook on the stove. A few years ago, it was a problem that our kitchen runs on gas, but it's very useful now.”

They have had no heating since January 10, and the electricity completely stopped working two days ago. She says that she tried to study hard during this time and scored 93 out of 100 on her exams. Now there will be a two-week break, although it's hard to call it a break under these circumstances, she said. "But at least we have this place," she commented, looking around the tent. “When it's cold outside, there's no one on the streets, but here we've formed a community. A few minutes ago, I helped a woman in her seventies order an indoor humidifier online because she had never done it before and didn't know how to.”

In 2022, when Russia attacked Ukraine, Margarita had just started high school, and today she is a freshman in college. "These should be the best years of my life, my teenage years and college," she said. "But I try to live with it and accept everything that happens." She lives with her mother; her father is fighting in the war. “ My father visited us a week ago and he was shocked by what he saw: at his current place of service they have electricity, but here, in the capital of Ukraine, we don't. He worries more about us than about himself: he is in a place where anything can happen at any time, while we only have to deal with the lack of water and electricity. Yet he worries more about us.”

In the initial years of the war, she made camouflage netting for her father's car on the front lines, using fishing nets and T-shirts from home. Recently, she also made a winter version, this time from white T-shirts because of the snow. She also sends money to the Ukrainian army every month.

“I'd like to do more. My dad always says that I'm already doing as much as I can by getting an education during wartime, and that the most we can do is support the army and each other. But I feel ashamed that I can't do more. My dad is away at war. I want to help Ukraine win. I have many friends who want to go abroad to study, for example nuclear physics, so that they could later bring their knowledge and innovation back to Ukraine. I also thought about studying abroad, but ended up staying. I want to be here, even if things end sadly for Ukraine. I want to be here in Ukraine, until the very end.”

The current assault on Kyiv's energy infrastructure is not the result of a single attack, but a series of systematic strikes that had been months in the making. Russia has been regularly attacking Ukraine's energy infrastructure since 2022, and the immediate precursor to the current escalation was a large-scale attack on October 3. At that time, 35 missiles and 60 drones were used to attack the Ukrainian gas network in the Kharkiv and Poltava regions, destroying 60 percent of Ukraine's gas production before winter even set in. This was also a significant blow to the power supply, as a large part of Ukraine's electricity is generated by gas-fired power plants. Later, moving from area to area, they targeted sub-stations and transformers, further damaging the infrastructure before the current winter.

An intense drone and missile attack left 6,000 buildings in Kyiv without heating on January 9. After the attack, Klitschko asked residents who were able to leave Kyiv to do so, in order to relieve pressure on the supply system.

On January 13, one of the coldest nights of this winter, the civilian infrastructure's energy supply came under another intense Russian attack. At that time, the weather service had already warned of nighttime temperatures around -20 degrees Celsius in Kyiv for the days ahead. The attack left 70 percent of the capital without power, causing such a severe power shortage that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky declared a state of emergency in the energy sector the following day.

Then, as dawn broke on January 20, Russia launched its third major wave of attacks, this time with 18 ballistic missiles, 15 cruise missiles, and 339 drones, targeting mainly Kyiv's infrastructure. The next attack took place in the early hours of Saturday, January 24, after which Ukrenergo, which operates the national power grid, warned that power outages were to be expected in 80 percent of the country.

The cold weather, unprecedented in recent years is not only making life difficult for civilians, but the sub-zero temperatures, the ice and the constant attacks are also significantly hampering the repairs of the infrastructure. Energy experts say that compared to the past few years, the current situation is the worst. In addition to exhausting civilians, Russia's goal with these attacks is to isolate industrial regions (Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia) from the main energy production centers.