The Hungarian story behind Klimt's record-breaking painting: Elisabeth Léderer was the daughter of a major industrialist from Győr

It made international headlines last November, when a late portrait by Gustav Klimt sold for $236.4 million, or nearly 78 billion forints. The work thus became the second most expensive painting ever auctioned, after Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi, and the most expensive modern painting in the world. The Hungarian media rushed to report on the amount, the excitement of the bidding war, and the new peak in the art market. However, there was little mention of the fact that the model for the portrait – not Elisabeth Lederer, but Erzsébet Léderer – had roots in Győr. She was not just a "Viennese lady," but the daughter of a Hungarian industrialist who left the banks of the Mosoni-Duna to enter the Central European art world. And this is not some kind of forced local patriotic exaggeration, but a historical fact.

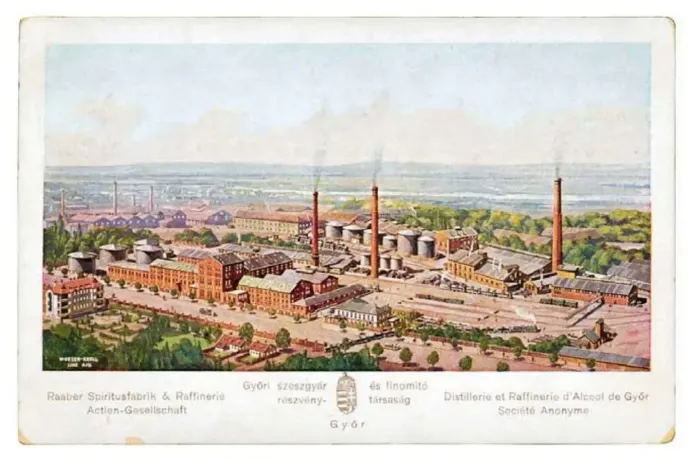

Erzsébet Léderer's father, Ágoston, was the owner of several Austrian factories, the CEO and main shareholder of the Győr Distillery and Refinery, and one of the key figures in the industrialization of the city. He played a key role in the period when Győr rose from a merchant town to a modern industrial city through conscious urban policy and radical structural change. The factory, founded in 1884 and on the verge of bankruptcy at the time of its launch, was saved by Léderer's capital, expertise, and the business network he had built between Vienna and Győr, which he reinforced with German, Austrian, and Czech networks. Under his leadership, the former "quasi-factory" became a modern, large-scale enterprise: a center of supporting industry that became one of the city's most reliable employers for a long time.

As a member of the board of directors, he participated in the work of several railway and industrial joint-stock companies and, as chairman, managed the city and county savings bank. Thanks to his dedication, during the Léderer era’s 41 years, the production of spirits in Győr flourished. He modernized the factory, put trade on track, and still had enough energy left to participate in the founding and development of the Hungarian Wagon and Machine Factory, which remained Győr's largest industrial enterprise until the regime change. The Győr press of the time reported hundreds of times on his family's charitable donations. According to local newspapers, his name was a "moral and financial guarantee" – both in economic life and in the maintenance of social institutions.

The industrial development of Győr took place in the second half of the 19th century, but it was no accident. The city's economic structure was redefined by Jewish entrepreneurs who, beginning in the 1850’s, brought capital, technology, and a modern business culture to the region. They established leading food and engineering plants, established the textile industry, and set up oil and match factories. By the turn of the century, this entrepreneurial class had created the first stable, multi-generational industrial base for capitalism in Győr; by 1910, 46.8 percent of the city's population was already living off industry, making Győr the most industrialized settlement in Hungary. Ágoston Léderer played a prominent role in this structural change. All this also created the socio-cultural background that enabled his daughter, Erzsébet, to find her way into the innermost circles of Viennese modernism – all the way to Gustav Klimt.

An empire that began in a rented workshop

In order to understand Ágoston Léderer's life journey, we must first look at his family background. The family's history did not begin with castles and works of art, but in a rented workshop in northern Czechia. Ignatz Lederer was born in 1820, at a time when Jewish families' movements, marriages, and livelihoods were still subject to strict legal restrictions. Ignatz was married in a synagogue and is buried in the Jewish section of Vienna's Central Cemetery. All this suggests that his religious affiliation was important to him, even if there are no sources documenting his involvement in the community.

Taking advantage of the edict of tolerance issued by Joseph II, Ignatz began to do business in the Czech-Moravian region. In 1859, he obtained an industrial license for his small, rented distilleries in Leipa (now Česká Lípa) and then in 1867 in Jungbunzlau (now Mladá Boleslav). This modest family business later became the basis for the "Jungbunzlauer Spiritus und Chemische Fabrik AG," registered in Prague in 1895, a company that was soon followed by the establishment of more factories, providing Ignatz's sons with a secure financial background.

Ignatz was particularly innovative: he switched from distilling potato spirits to the higher-quality sugar beet spirits and demonstrated a level of environmental awareness well ahead of his time by utilizing by-products of the manufacturing process, such as potash. His products were used in a number of industries, from glass manufacturing to soap making. The successful development of these businesses quickly brought financial prosperity to the family. Ignatz was known for regularly supporting the needy in his community.

One of the most extraordinary art-collecting couples of the Monarchy

In the second half of the 19th century, a huge population movement began from the Czech-Moravian regions to Vienna, and the Léderer family was no exception. By the time of his death in 1896, Ignatz was already living in Vienna. He was convinced that it was only here that the industrial empire he had built could become truly profitable and internationally integrated. It was this multifaceted entrepreneurial background, rooted in Bohemia and Moravia and centered in Vienna, that provided the economic foundation from which Ágoston Léderer's career in Győr later grew, and on which he built his marriage to Szeréna Szidónia Pulitzer in 1892. The ceremony was conducted according to Jewish rites by the chief rabbi of Győr.

The Léderers lived in downtown Vienna, but they also owned significant estates and industrial interests in Győr. Their home was one of the hubs of artistic life at the turn of the century. By this time, Ágoston Léderer was among the thousand wealthiest businessmen in the 50-million-strong Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. His family had considerable experience in the distilling and chemical industries, and he himself had learned the trade in Vienna, then continued his education on study trips abroad.

The marriage proved to be of outstanding importance in both social and economic terms. Szeréna Szidónia Pulitzer, who was born in Makó and after whose cousin the Pulitzer Prize was later named, brought a dowry worth approximately €1.3 million in today's money, or half a billion forints, into the marriage. This capital enabled Ágoston Léderer to become the majority shareholder of the aforementioned distillery in Győr, which he went on to manage for 41 years. The family moved from Vienna to Győr in 1911, where Léderer also acquired Hungarian citizenship. The industrialist, who was trained as an economist and chemist, became one of the multimillionaires of the early 20th century. The factory still stands today, and operates under the name Győri Szeszgyár és Finomító Zrt. (Győr Distillery and Refinery Ltd.). However, the name of the late CEO is hardly remembered today.

The Léderers stood out not only for their wealth, but also for their passion for art. Ágoston and Szeréna were among the most enthusiastic art collectors in the Monarchy: they regularly attended auctions in Paris, London, and Berlin, where they tended to buy works for astonishing sums. Ágoston was passionate about late Renaissance and early Baroque Italian art. He had a unique collection of 16th-century bronze pieces – one that was considered rare even among the art patrons of Vienna at the time.

Szeréna became more interested in the modern era. She was a regular visitor and buyer at the Wiener Werkstätte exhibitions, became an enthusiastic supporter of Viennese Art Nouveau, and a follower of everything that defined turn-of-the-century Viennese modernity. Her extravagant clothes were designed by the famous fashion designer of the time, Emilie Flöge, and her thinking was shaped by Freud's teachings. In other words, she represented everything that constituted the intellectual and visual center of Viennese social life at the time, and raised their children surrounded by this world. Erzsébet followed her parents' passion for art as a sculptor, while Erik became an art collector. Thus, it is not surprising that the daughter of a Győr industrialist was able to enter the inner circle of Viennese modernism.

Friendship, art, and the birth of an iconic portrait

Around the turn of the century, the Léderers met the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, who was already gaining influence at the time. In 1897, Klimt and several of his fellow artists staged a high-profile departure from the conservative Künstlerhaus and founded the Wiener Secession movement. The group's goal was to break away from the shackles of official academic art and make room for modern forms, new aesthetics, and international trends. It was in this vibrant, innovative milieu that the art-loving Léderers became acquainted with Klimt—and this led to Erzsébet Léderer later becoming one of the painter's most important portrait subjects.

The Léderers thus cultivated a close and friendly relationship with the young, talented Gustav Klimt, who quickly became one of the celebrated figures of Viennese society at the turn of the century. Klimt worked in a variety of genres, but he became particularly famous for painting the prominent women of his time, including Szeréna Léderer. The full-length portrait of her was presented at the 10th exhibition of the Secession in 1901, which quickly became one of Klimt's most famous works.

Szeréna was an avid fan of the painter's work and literally spent a fortune to decorate the salon of her Viennese home with Klimt's paintings and drawings. Her enthusiasm for art went so far that one of Klimt's most provocative and best-known works, the 24-meter-long Beethoven Frieze, found a home—at least temporarily—in Szeréna Léderer's salon. This gesture perfectly illustrates that the family became one of the most important patrons of Viennese modernism. This close personal and artistic relationship later bore fruit in the form of a portrait, which is now the second most expensive painting ever sold at an auction, and whose model was the daughter of a wealthy industrialist from Győr.

Schiele and the Léderer family: an artistic friendship in Győr

Thanks to their close relationship with Klimt, the Léderer family also befriended the young and exceptionally talented Egon Schiele, whom Klimt introduced to them as a particularly good friend of his. Schiele quickly gained the family's trust: he worked with the eldest son, Erich Léderer in painting classes and mentored him during the first steps of his artistic career. 1911 was a turning point, as the Léderers moved to Győr and Schiele lived as a guest in their home for a whole year. The period also became an important chapter in Schiele's oeuvre, as he painted his now famous picture of the Goat-Footed Bridge in Győr and created several portraits of Erich as well. The Klimt–Schiele–Léderer relationship is a rare example of a major industrialist family from Győr becoming an integral part of the intellectual and artistic milieu of the Viennese avant-garde.

At the time of his death in 1936, Ágoston Léderer resided in Vienna on one of the most prestigious streets of the Innere Stadt, in close proximity to the parliamentary district, the Justizpalast, and the Hofburg. This address clearly shows his integration into the Viennese high-capital and upper-class elite, and indicates that his family was part of the social and cultural center of the Monarchy's capital. The Wiener Salonblatt bid him farewell with the following words: “As a serious collector, he attended every major auction held in Paris, London, or Berlin, and at these events, the calm and exceptionally intelligent gentleman was accompanied by an impressively beautiful woman whose dark, sparkling eyes charmed everyone. Over the course of several decades, they gained recognition as avid collectors who had become unequivocal experts.”

Then came 1938 and the Anschluss, which was devastating for the Léderer family. The National Socialists Aryanized the company in Jungbunzlau and confiscated all of the family's property. Having become completely destitute – and being a Hungarian citizen – Szeréna fled to Hungary in 1938, where she died in 1943. Their daughter, Erzsébet – whose Aryan husband suddenly divorced her after the Anschluss – also arrived in Hungary penniless and outlived her mother only by a year. The two brothers, Erich and Fritz fled abroad in 1938. Erich and his wife settled in Geneva, where, until his death in 1995, he made it his life's goal to recover his parents' property, which proved to be an impossible undertaking. The Nazis transported the Léderers' Klimt collection to a castle in Lower Austria, and before they withdrew from Austria, on May 8, 1945, they booby-trapped and set fire to the castle where the art treasures and paintings were stored.

This was glossed over in the Hungarian press at the time, which focused on the value of the works and Erzsébet's escape from the Holocaust, but hardly mentioned her connection to Győr— or the fact that she was the child of one of the city's most important industrial dynasties. It was as if the Hungarian story behind the portrait was invisible. As if the Jewish industrialists who modernized Győr had not written their names in the city's history. And yet it was these entrepreneurs who gave Győr its industrial start and ensured the city's development right up until World War II. And the person who connected this network to Vienna, who integrated it, and elevated it to national status was Ágoston Léderer, whose daughter is featured in the record-breaking artwork. It is as if the portrait had no Hungarian connection, as if it did not belong to the same story that came to an end with a Klimt masterpiece sold at Sotheby's auction.

And yet, it is worth noting that this portrait is also a Hungarian story. Although Klimt's world record-breaking painting was created in Vienna, its roots reach deep into the soil of the industrial city of Győr. The full-length portrait is not only a masterpiece of art history, but also a visual imprint of the rise of Hungarian Jewry. It is a portrait of an era when Jewish and non-Jewish entrepreneurs joined forces to shape the image of Győr, and when the city's industry claimed its place not only on the economic map of Hungary, but also on that of Europe.

Therefore, the record-breaking price of the Klimt painting is not only news for the art market. It is a memorial to a woman who appears in the most prestigious iconography of art—and who, in doing so, brings back into the spotlight the city, the family, and the economic and cultural world she came from.