Vasarely's last great optical illusion has jumped off the canvas and distorted reality

In the early morning hours of April 11 2023, an armed FBI task force rang the doorbell at the home of an 82-year-old French woman in Puerto Rico. Their guns did not have an active role that day, but the raid still received worldwide coverage. Ever since then locals have been tacking on new details to the story, which a year and a half later is still being hailed as one of the most exciting events in the recent history of the capital, San Juan.

It wasn't drugs or weapons that the FBI was looking for in the former Vatican building known as Colegio de Párvulos, but 112 works of art produced in France about half a century earlier by artists Victor Vasarely and his son Yvaral.

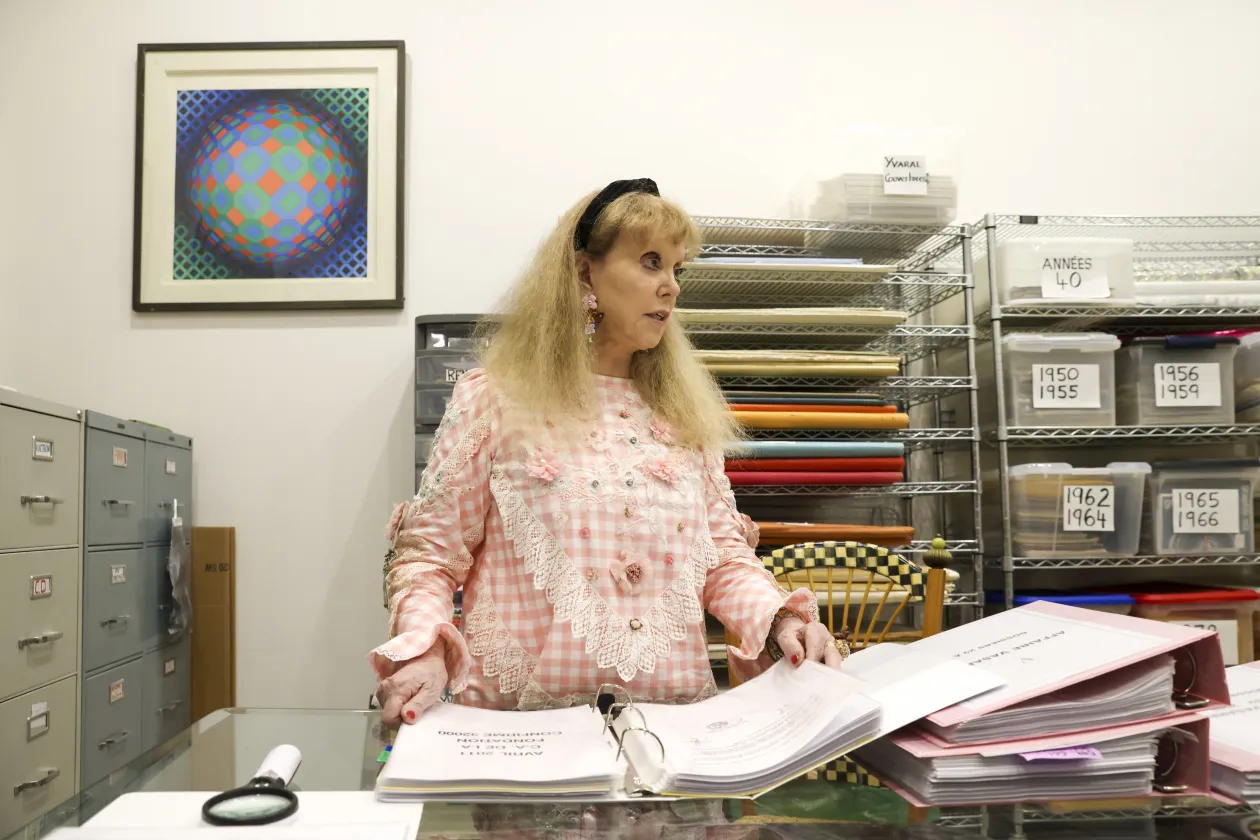

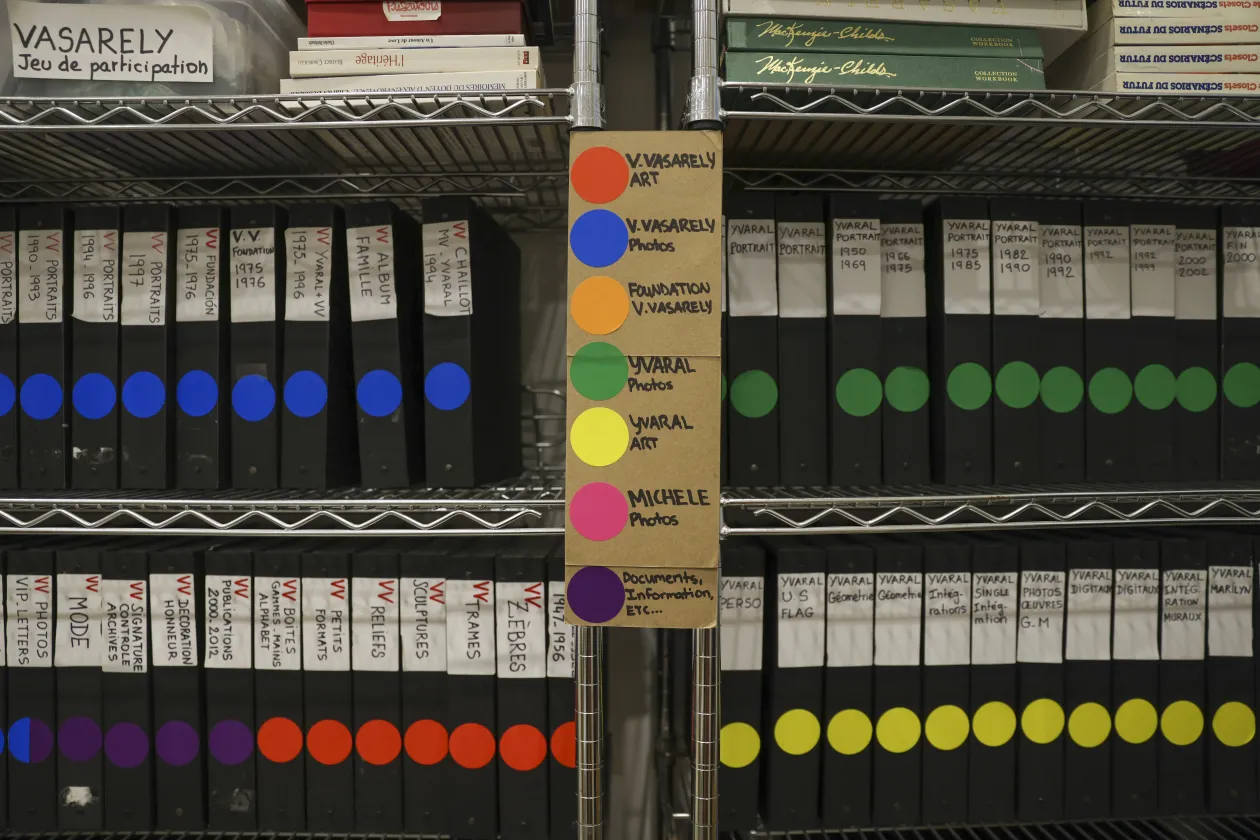

Michèle Taburno-Vasarely, the daughter-in-law of the world-famous artist, woke up early that morning to a call from the FBI. Still half asleep, she thought she was hearing the sounds of a narcotics bust filtering into her bedroom. She got up, petted one of her cats, and when she saw the commandos outside her door, reality struck her. The FBI had given her advance notice that they planned on seizing the artwork from her, so she had already carefully packed and labeled the requested pieces the day before. But the time and manner of the agents' arrival took her by surprise, nearly giving her a heart attack. Although being offered to be taken to the hospital, she declined so as not to leave her cats unattended. A few hours later, she was giving an impromptu art history lesson to interested FBI agents while other investigators were loading op-art masterpieces into a truck.

According to reports, the US investigators had brought along surprise guests, the French authorities, led by Serge Tournaire. Tournaire is the chief investigating judge at the Paris court, and according to one legal source with insight into the case, the fact that the Formula-1-calibre investigating judge personally supervised the operation could be seen as a demonstration of political force to boost French nationalist sentiment. Articles reporting on the event also reveal that some artwork was simply lifted off the wall and – quite unprofessionally – placed straight into the truck. One can only hope that after the raid, the paintings finally arrived intact at their undisclosed destination, generally believed to be a Caribbean warehouse.

The FBI's intervention is – presumably – the final chapter in a criminal investigation that has been ongoing since 2009. Put simply, the gist of this intricate conflict is that Pierre Vasarely, grandson of Victor Vasarely, stepson of the Puerto Rico-based Michèle Taburno-Vasarely – and not least the head of the Vasarely Foundation in France – has been working for years to recover works of art taken from the Foundation between 1995 and 1997. According to him, these include the works of art seized by the FBI, which Michèle Taburno-Vasarely illegally possessed and must therefore be returned to the Vasarely Foundation in Aix-en-Provence. His stepmother says that this assessment is inaccurate because, although these works were once the property of the Foundation, they were later officially transferred to Vasarely's sons and she then received them as a gift – also officially.

Now 64 years old, Pierre Vasarely has filed quite a few lawsuits in his lifetime, some of them against his stepmother; the current action was not brought by him, but by a certain Xavier Huertas, who is not too far from the Aix-en-Provence Foundation: he was appointed its administrator in 2007. After going through several levels of the French justice system and six investigating judges, the case reached the point where the FBI, under the terms of the US-France Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty, knocked on the door of the house full of art and cats in the old town of San Juan. (For more cinematic details of the event, check out our interview with Michéle Taburno-Vasarely, coming soon.)

Pierre Vasarely had hoped that the Vasarely Foundation would get back the 112 works of art following the raid, which according to local newspapers targeted art worth $40 million. The very next day, however, Michèle Taburno-Vasarely filed an appeal with the local court. We contacted the FBI for details on the case, but they politely declined to comment.

The fate of the works of art will be determined by the outcome of the long drawn-out legal process. Will the works of Victor Vasarely and his son Yvaral ever make it back to their native France? And even more importantly, will a feud that has been going on for more than three decades – at times like a crime thriller, at others a tragicomedy – ever come to a conclusion? Whatever the answer, the feud has achieved one thing for sure: it has overshadowed Victor Vasarely's body of work.

The following spring, in April 2024, just thirteen thousand kilometres away, other works of art by Victor Vasarely were on their way home from South Korea to Budapest. It was then that we decided to delve deeper into the case that had been referred to in the press for years as the Vasarely Affair. Fortunely for the artwork, their shipping crates were safe, the mood surrounding them however was a bit of a powder keg: from the moment the Vasarely Museum in Budapest loaned out most of its collection to the Korean exhibition, Vasarely's grandson Pierre watched the events in East Asia from his base in Aix-en-Provence with a furrowed brow. He did not grant the so-called reproduction rights for the exhibition, which meant, among many other things, that the exhibition was held but could not be effectively advertised. As a result, the anticipated resounding public reception and the organizer's revenues fell far short of expectations. The Hungarian side did not suffer any losses, as the Korean exhibition did not involve any expenses for the Vasarely Museum and its umbrella institution, the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, but it was the umpteenth embarrassing fiasco in the international art world that the Vasarely Affair had played a role in.

With this turn of events this spring, the legal trench war that has been raging for decades finally made direct contact with Hungary. Digging through articles in the international press, it was difficult at first to get a sense of the feud between grandson Pierre Vasarely and daughter-in-law Michèle Taburno-Vasarely. Moreover, two things were not known at the time. One was that we were about to encounter two personal realities that were light years apart; the other was that if there was one story that perfectly fit the image of a chaotic beehive, it was this one. This fog gradually lifted, but a few questions remained. And the assessment of said questions depends on one's vantage point – just as when one stands in front of Vasarely's monumental works: if one looks at them from one direction, the painting seems to bulge outwards from the plane; but if from the other, it appears to sink into the wall.

How did we get here?

Victor Vasarely, aka Győző Vásárhelyi, the most famous Hungarian-born artist of the second half of the 20th century, the father of op-art, died on 15 March 1997. During his lifetime, his optically challenging works of art were viewed by millions – which was precisely his aim: to make his work accessible to the masses under the motto „art for all”. He enjoyed success during his lifetime and was a living legend even outside his chosen homeland of France. His artistic legacy consists of thousands of works of art, which are at the center of a debate intertwining family relationships, the art world, missing works of art, money, intrigue, Aix-en-Provence, Paris, Chicago, Puerto Rico, Budapest and Pécs. As to what the Vasarely affair is, again, it depends on the perspective from which one looks at the matter – after all, Vasarely's art is nothing but an optical illusion – it can be an inheritance dispute, a criminal lawsuit, a family feud, or a political matter. What is certain is that lawsuits whirl through the story like Chinese porcelain in other families.

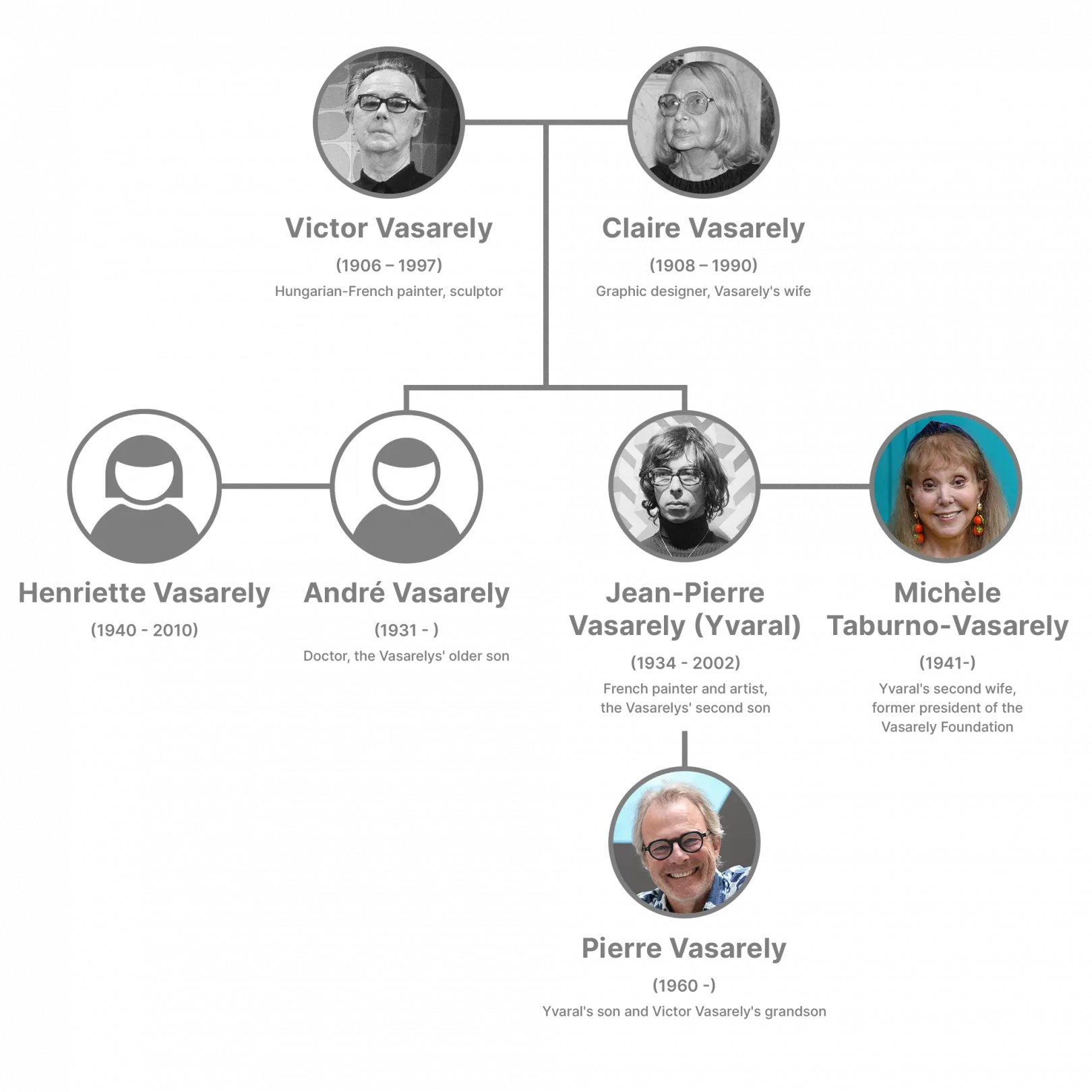

The infighting began more than thirty years ago, when Vasarely's wife Claire died in 1990. The principal protagonists at the time were the heirs in search of justice, Victor and Claire Vasarely's two sons and their wives. Today, only two are left to continue the battle: the daughter-in-law living in Puerto Rico and the grandson based in Aix-en-Provence. To recap, the daughter-in-law is Michèle Taburno-Vasarely, the second wife of Vasarely's son Jean-Pierre. The grandson, Pierre Vasarely, is Jean-Pierre's son from his first marriage, who as a young child would embarrass the world-famous grandfather's Hungarian guests with a smattering of Hungarian swearwords. Later, after expanding his Hungarian vocabulary a bit, he gradually became involved in the Vasarely Foundation, which has been active since the early 1970s, and since 2009, he has been the director of the foundation in Aix-en Provence in the south of France.

And we have already arrived at the point in the narrative where one of them would tap me on the shoulder to point out that the fight is not really between them, but between the daughter-in-law and the French justice system; and then another would politely cough saying that it is not like that at all, because Pierre, the grandson of Vasarely, is systematically ruining her life and tarnishing the artist's name by obsessively suing – not only her, but half the art world. It's just a small but typical example of how the tale of their skirmishes is a convoluted one, and the overlapping patch between the two protagonists' realities is but a thin sliver. If you listen to either of them for hours, you can immerse yourself in their respective truths, but for every argument one of them makes, there is a counterargument, and for the counterargument comes another counterargument, and so on. It is not surprising that the international press often describes the Vasarely affair as 'convoluted', 'complicated', 'dark', 'tangled'.

It is worth noting at the outset that it is not only Victor Vasarely's heirs who have been in dispute over inheritance. The roughly fifty heirs of the Picasso family initially fought similar battles, only to come to an agreement – in deference to the dearly departed Picasso. Most inheritance disputes eventually reach a resolution. There were fleeting moments during the Vasarely feud when it seemed as if the trenches would finally be filled in, but in the end it never came to pass.

„The Vasarely heirs are not a unique case, especially when the artist has a more extensive artistic legacy – which means that they are often artists who were already recognised during their lifetime and who have a significant body of work. Looking at this case from a professional point of view, it is a typical inheritance dispute in this area,” explains Dr Katalin Andreides, a lawyer specialising in legal issues concerning art collections. Her work involves advising international collectors, galleries, museums, artists and foundations on matters such as transactions, ownership disputes and provenance issues.

„In the case of works of art, the artist is entitled to a set of copyrights, which can be claimed by the heirs or the person administering the estate upon the artist's death,” explains the lawyer. „The situation is further complicated by the fact that not only the works of art but also the copyrights themselves represent a considerable asset. For this reason, it makes a difference to whom the various rights belong,” says Katalin Andreides. A striking example of this was the Korean commotion arising from reproduction rights.

The Hungarian story arc

While it was less action-packed than the FBI's extraction from Puerto Rico, the Korean incident this past spring, which directly affected Hungary, gave plenty of cause for anxiety. Just one year ago, on December 21, 2023, the aforementioned Vasarely exhibition opened in Seoul, South Korea. All the items in the exhibition came from the collection of the Vasarely Museum in Budapest.

Márton Orosz has been running the museum since 2014, which was opened in 1987 thanks to donations from Victor Vasarely and his wife Claire. In September 2023, he said, he had been asked to organize a Vasarely exhibition in Seoul at the end of the year to fill a four-month gap at the Hangaram Art Museum. The exhibition was organized by the Seoul Art Center to mark the 33rd anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between South Korea and Hungary.

The deadline was therefore unusually tight, especially for borrowing works from elsewhere. „Normally, it takes at least a year to prepare an exhibition, but usually two, and it's common to borrow from several places, such as museums or private collections. In this situation, it would have been a lot of extra work, and it would not have been possible to meet the deadline, so it was only at the last minute that we managed to organize the transport, the insurance, and all the paperwork,” explained Márton Orosz.

Pierre Vasarely strongly objected to this – so much so that in the end, while the other rights holder, Michèle Taburno-Vasarely, gave the go-ahead for the exhibition in Puerto Rico, he did not grant the reproduction rights, which in practice means that he did not consent to the advertising and merchandising of the exhibition. (Property rights include reproduction and copying. Reproduction rights are usually divided between heirs. A typical example is the reproduction of a work of art and the publication and distribution of photographs of it in auction or exhibition catalogues. This requires the consent of the artist or the heirs/administrators of the estate, as well as a fee.) If any of the rights holders says no, then any go-aheads from the others are in vain. From there it was doomed to failure, at least in the case of Seoul, with a significant drop in visitor numbers.

In the next part of our series, Pierre Vasarely will talk about why he made this decision, but here are his reasons in brief: one was that the museum in Budapest was left practically empty for the months-long exhibition in Korea, and, according to him, this was certainly contrary to his grandparents' original intentions. When they had made the donation, he said, they could not have been thinking „one day the museum will be emptied for a period of months”. He was also worried about the security risks involved in transporting the collection. Nor did he look favourably on the fact that Martin Orosz had become a scientific advisor to the Michèle Vasarely Foundation in Puerto Rico. Pierre Vasarely probably took this to mean that the Budapest museum had chosen sides in the inheritance dispute and supported his stepmother.

We asked László Baán, Director General of the Museum of Fine Arts – which includes the Vasarely Museum in Budapest – about the matter, and he told us that as far as the Victor Vasarely collection in Budapest is concerned, „the museum always complies with the relevant donation agreements and the founding charter of the Vasarely Museum.” In response to Pierre Vasarely's argument, Márton Orosz replied that collection exhibitions take place all over the world: „It's not the first time for the Vasarely Museum in Budapest, and the Louvre, for example, has also had its major works travel to Abu Dhabi for extended periods. In the 2010s, several European museums, such as the Louvre in Paris or the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, hosted major works of the Fine Arts Museum, and an exhibition of the collection has also travelled to Buenos Aires.”

The exhibition, entitled „Treasures from Budapest”, opened in Seoul at the end of December with the subheading „The responsive eye” (the subheading can also be interpreted as an homage to the 1965 MoMA exhibition of the same name in New York, one of the largest showcases of op-art and kinetic art in the world, which featured works by nearly a hundred artists, including Vasarely). The museum located in the heart of Óbuda was not closed for the duration of the exhibition – some works were not even loaned out – but continued to operate with a temporary alternative exhibition. In the absence of Vasarely's works, visitors were welcomed by an exhibition of posters curated by internationally renowned Vasarely collector and expert Bruno Fabre.

The Korean exhibition eventually concluded in the second half of April this past year, and the works of art returned to Budapest by the end of the month. The organizers had expected around 250,000 visitors – which would have generated enough revenue from ticket sales to cover the cost of the exhibition – but instead a mere 25,000 people attended. All the costs of the exhibition were borne by the Korean organizer. (We sent questions to the organizer about the event, but had not received a reply by the time of this article's publication.)

Following the Korean fiasco, it is clear that the effects of the three-decade feud between Pierre Vasarely and his stepmother have been felt in Hungary. Although representatives of Pécs's cultural scene, which has been fully supportive of Pierre, have condemned Budapest's Korean exhibition, the management of the Vasarely Museum in Pécs has expressed itself in much more restrained terms:

„The conflict between the heirs has no impact on us, the two museums in Hungary, because there is no conflict between us. There is an implicit tension in the situation, and we would like to remove ourselves from it,” explained Katalin Getto, the museum curator in charge of the Vasarely collection in Pécs. She has held this position since 2019, and her predecessor, József Sárkány, had a close relationship with Pierre Vasarely. „At the same time, I felt that it was impossible not to take sides in this story, and Pierre contributes a color to the cultural life of Pécs that is definitely worth preserving,” she added.

László Baán shared the same opinion as Katalin Getto: „We are not aware of any tension between the Vasarely Museum in Budapest and the Vasarely Museum in Pécs. The staff at our institutions have an excellent professional and collegial relationship, which is demonstrated by our joint projects.” Baán added that it is not the role of the Museum of Fine Arts to take a position on an artist's estate or on a possible dispute between heirs.

The museums of Pécs and Budapest also play an important role for Aix-en-Provence: these two collections are frequent partners in lending works of art, so a good relationship is in the interest of all parties involved.

Like cats and dogs

Katalin Getto is right: when it comes to the Vasarely affair, it is difficult for anyone to take the middle ground. We have spoken to a number of people in the process of gathering material, but we never met anyone who had been on good terms with both sides simultaneously for a long period of time. The reason for this is that once you get drawn into the Vasarely affair, sooner or later you have to make a choice. Both Michèle Taburno-Vasarely and Pierre Vasarely now have a number of influential and internationally renowned experts in their camps, but the battle is nevertheless not evenly matched: „There are two completely different weight classes fighting it out here,” says Márton Orosz, director of the Vasarely Museum in Budapest, „Michèle doesn't have a staff in Puerto Rico but just one or two assistants – she's essentially jousting windmills. Pierre's foundation has a substantial staff, the Vasarely Foundation is supported by the French state, and in terms of litigation, he's on his home turf.”

In this series of articles, our aim is not to take sides. We simply want to present a glimpse into one of the most exciting family feuds of the early 21st century – one that, if it were in a Netflix series, you would say the screenwriter has an overactive imagination.

Let's take a look at the combatants.

Michèle Taburno-Vasarely does not fit the profile of the typical widow in her mid-eighties as suggested by her age or family status: she is active, full of life and her memory seems to have not let her down. She is meticulous about her appearance, as she is about the living space she has painstakingly created and now shares with her cats. She doesn't shy away from excess, be it in cat ownership or in home decor. Her well-wishers say she's polite and witty, a remarkable genius, whereas her critics consider her to be cunning and only interested in money. „She is a gifted communicator with strong advocacy skills and good at managing people. At the same time, she's a very likeable person and a fierce advocate for artists,” one of her acquaintances told us.

She lives in a quaint old house renovated from a former Vatican dormitory in the old town of San Juan, Puerto Rico, where the FBI dropped by for a visit. Puerto Rico is an associate state of the US, enjoying a milder climate, more sunshine and lower taxes than the continental US. It's where she registered her own foundation, the Michèle Vasarely Foundation. Her name has popped up in the French and international press for years due to the Vasarely affair, but after the FBI seized 112 works of art from her last April – a result of the affair – she is now more widely associated with this movie-like action sequence.

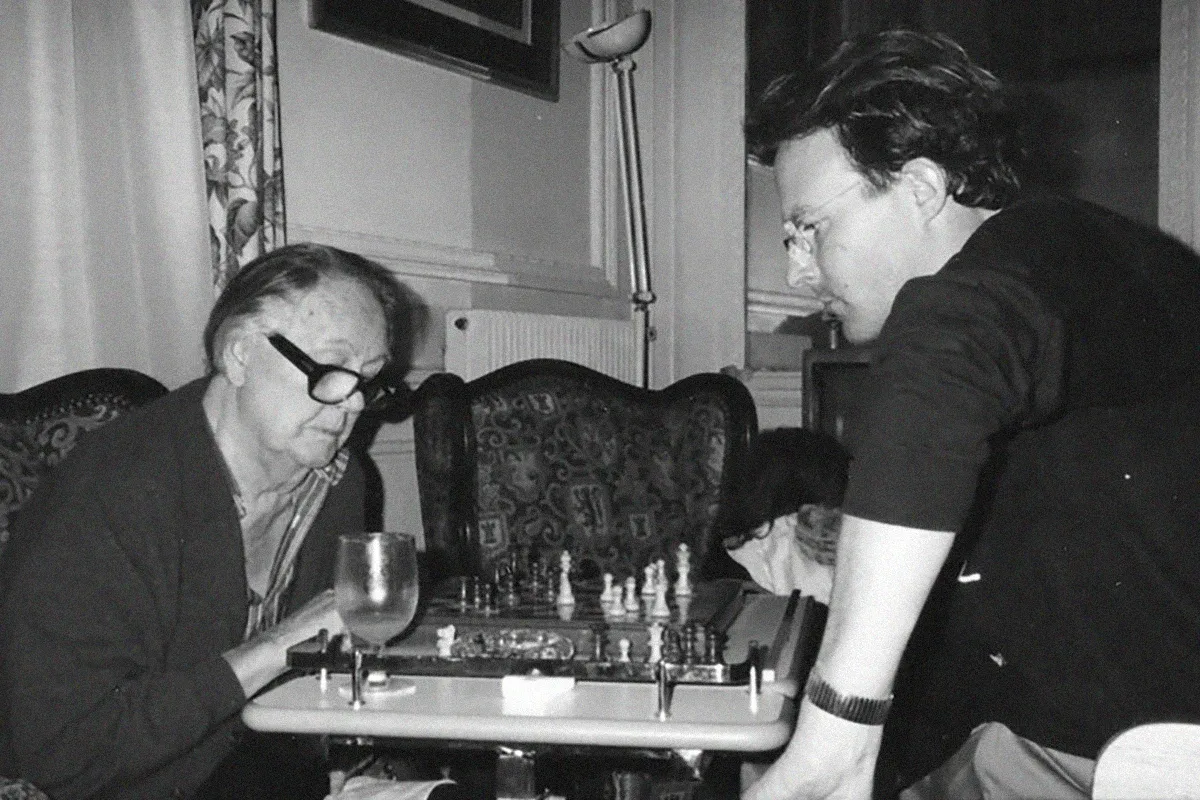

Victor Vasarely's grandson is, as it were, Michèle's stepson, although he never regarded his father's second wife as part of the family, and he also tried to sue her for the Vasarely name (unsuccessfully). He is half Hungarian through his grandparents, which he is proud of. An acquaintance of his describes him in glowing terms: 'A good sense of humour, outspoken, generous, hospitable, warm-hearted, charming. He's very playful and can instantly hit it off with others. It's almost as if he's playing on a chess board. He also has great advocacy skills. With his European style and understated elegance, he too could subtract a few years from his age. His critics say that, apart from his childhood, he only ever sought out his grandfather when he needed something; his only way of solving problems is through litigation, and he has instigated a host of civil and criminal lawsuits, which reportedly has made the art world wary of him. He visits Pécs, Vasarely's birthplace regularly, and enjoys great popularity and esteem, and in 2013 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Senate of the University of Pécs.

We met up with him at the museum of the Vasarely Foundation in Aix-en-Provence, where we chatted for hours in the company of his dog, but only after having toured the grandiose exhibition of the foundation set up by his grandparents, which is slowly being restored to its former glory.

The story

As already mentioned, the first dispute over the inheritance of Vasarely's estate erupted after the death of his wife Claire in 1990, and then was reignited seven years later with the death of Victor himself. But how did Vasarely's life's work become so vast as to fuel a decade-long feud in the first place? To find the answer, it is worth briefly going over the history and significance of Victor Vasarely.

Victor Vasarely was born in Pécs in 1906, moved to Paris at the age of 24, and worked as a graphic designer for several years, producing advertising supplements for medical publications and designing posters. He was soon joined by his future wife, Klára Spinner, herself an artist, who met him at Sándor Bortnyik's aptly named Workshop, a private school of graphic design in Budapest based on Bauhaus principles. They married and soon had two sons, André and Jean-Pierre. Vasarely adapted his original Hungarian name, Győző Vásárhelyi, to the French language, resulting in Victor Vasarely, and Klára, whom the family called Bonzi, began to use the French equivalent of her name, Claire.

Vasarely became a French citizen in the early 1960s, and in 1976 the Fondation Vasarely – Centre Architectonique (Vasarely Foundation – Architectural Center), based on his designs, opened in Aix-en-Provence. For many years he served as honorary president of the Foundation, but from 1981 the organization was run for more than a decade by Charles Debbasch, Dean of the University of Aix-Marseille. Vasarely suffered from Alzheimer's disease during the last years of his life, although the exact duration and extent of his illness remain disputed. In any case, he spent the last three and a half years of his life in a private institution, fairly isolated from the outside world. Many blame his sons and their wives for putting the nearly ninety-year-old artist in an institution. One of our sources with insight into the case gave us a 1996 Le Figaro article as proof that he was lucid right up to the very end of his life.

By then, their two sons had grown up: the elder, André, became a doctor, while the younger, Jean-Pierre, became a well-known artist under the name Yvaral. The name Yvaral is short for Yves Aral, an anagram of Vasarely – a pseudonym the young Jean-Pierre wanted to use to distance himself as an artist from his father. In 1960, his first wife gave birth to a son, Pierre, and three years later he met Michèle Taburno-Vasarely, his second wife. Yvaral passed away from cancer in 2002.

Little Pierre – as his grandfather called him – is Victor Vasarely's only known grandson. However, a few years ago, a possible cousin of Pierre appeared, a Belgian man by the name of Xavier Terlet, who claims to be André's illegitimate son, but so far he has not come forward with any claims. Victor Vasarely's other son André is still alive at 93 years old and has lost his short-term memory, but the Hungarian language he used as a child often resurfaces in his mind. For years he has been looked after by his nephew Pierre. His passing will almost certainly mean another shuffle of the deck.

But back to Debbasch, university dean and president of the Vasarely Foundation, who plays an integral role in the story. As it turned out, he had been embezzling and looting from the Vasarely Foundation between 1987 and 1992, and the family also attributed the disappearance of the hundreds of artworks to him. In late 1994, Debbasch was accused of misappropriating funds. After refusing to cooperate with the authorities, he was arrested and imprisoned in Marseille. A year later, he fled to Togo to escape prosecution.

The Vasarely Foundation was registered at the beginning of the 1970s and was first located in the Château de Gordes, the castle in Gordes that Vasarely had renovated, and then in Aix-en-Provence from 1976. But why does an artist need a foundation at all? Primarily, it's because the question of who manages the artist's estate, his artistic property, is a very important issue. „The most typical way to do this, as was the case with Vasarely, is to set up a foundation during the artist's lifetime to continue to manage the artist's estate after his death,” explains lawyer Katalin Andreides, the expert cited previously on the subject. „For example, they record which public and private collections hold the works of art. The way in which an artist's estate is handled determines to a large extent how they are perceived in the present.”

Vasarely was a generous artist, donating hundreds of works to his foundation during his lifetime. And this is where the clouds began to gather, with the death of Claire Vasarely in 1990.

„My father and my uncle André were members of the Foundation's board for 25 years, and four years after my grandmother's death, they felt excluded from the inheritance as heirs,” recalls the grandson. The heirs, André, Jean-Pierre and their wives, found the solution to the situation by setting up an arbitration tribunal. The decision was taken in 1995, two years before Vasarely's death, by the Foundation's board of directors, which was chaired at the time by Michèle Taburno-Vasarely.

In lay terms, arbitration means that the parties do not take a civil case to a public court, but instead go to a private court. The parties have an equal say in who sits on the arbitration tribunal. In the mid-1990s, the arbitration tribunal ruled that Victor Vasarely had donated too many works of art to the foundation, thereby adversely affecting his sons, and that the foundation should pay 950 million francs to Vasarely's two sons. The foundation lacked the funds to do this as it was struggling financially, so in the spring of 1997, it filed for bankruptcy and the museum at the Gordes Castle closed. In Pierre's view, his stepmother was the cunning mastermind of this colossal plunder.

Nearly 400 works of art, mainly from Gordes, went to the heirs, Vasarely's two sons, (some of which went to Michèle, the oft-mentioned 112 works of art fall into this category). After numerous legal proceedings, an unappealable court ruling in 2014 and 2015 finally declared the arbitration procedure invalid and that it was only there „as a sham measure created by the Vasarely heirs to protect their interests”. The ruling also included the return of the remaining paintings to the Foundation. From there, Pierre Vasarely's ongoing pursuit of the paintings began. One of his oft-repeated phrases is „the works of art must return to the Vasarely Foundation.”

One of the most commonly accepted views is that it was not because Vasarely was insensitive to his family members that he filled his foundation with art, but rather because he deeply believed that art should not be the privilege of a few wealthy people. It was also because he was so far removed from the practical side of life, including the law, that he failed to consider the possible consequences of his decision. „In France, children cannot be excluded from their inheritance. Victor Vasarely was an artist who was particularly distanced from the law and the legal system, and he unwittingly excluded his children through his large donations to various organizations or individuals,” is how Michèle Taburno-Vasarely interprets the events.

The ill Vasarely watched the mismanagement of his sons and daughters-in-law from afar and passed away in 1997. The controversy surrounding his will after his death further ruffled feathers. Following a 1991 will designating Vasarely's youngest son Jean-Pierre as the sole heir to his moral rights, a will dated from April 1993 emerged, which stated that his grandson Pierre would be the sole guardian of the artist's estate and universal heir, and that he would also hold the artist's moral rights. The moral rights (aka droit moral) ensure that the artist's name, status and works will continue to be respected.

„Moral rights often represent a huge market-shaping power in the hands of heirs or estate foundations, especially in the case of famous artists like Vasarely. This is evident when you consider that after the artist's death they are the ones who decide which works belong in the artist's legacy, which works can be included in the artist's archive, which works can be published, and which works are certified as authentic,” explained Katalin Andreides. Initially the moral rights were exercised by Michèle, and were transferred to Pierre after a subsequent lawsuit.

In 2015, the French Supreme Court finally acknowledged the 1993 will as authentic, making Pierre Vasarely the universal heir. According to a source familiar with French legislation, this title of „légataire universel de l'artiste” denotes a social distinction rather than a moral inheritance or the exclusive right to exercise reproductive rights. But one of our legal experts says that the title also implies specific property rights.

In 1998 Pierre made a bold entrance into the inheritance controversy: he sued his father Yvaral and his uncle Andre for refusing to acknowledge the second will of '93, which he benefited from, and for suspecting him for years of dictating the text to the well-meaning Vasarely. Finally, the following year, the court ruled that there was no reason to doubt the artist's mental capacity at the time of the '93 will.

Almost in parallel with Vasarely's decline in popularity, the monumental building of the Foundation in Aix-en-Provence began to deteriorate, with the ceiling leaking and the works of art in danger. In 2010, a petition was launched to get the French government to save the building after it was feared that it would meet the same fate as the Château de Gordes and could be closed. Today, the foundation is under government supervision and restoration work is still ongoing.

The man at the center of it all

If you've been keeping up with the story so far, you're likely to be feeling tired or confused by now, which is perfectly understandable. As this deluge of information settles in, we might as well take a look at how Vasarely lived and worked, and what he contributed to the world. We spoke to five people who knew the master personally, and in the process of sketching out the portrait of his character, an unexpected harmony emerged: although he was generally perceived as aloof, he was described as a kind, generous man who obsessed over and prioritized his work above all else.

„In some ways he came across as a very stern man. He had an incredible aura that commanded respect. When he stepped into a place – an exhibition opening, a restaurant or anywhere else – people would fall silent and their eyes would be drawn to him,” says his grandson. „Many people thought he was very serious, perhaps even haughty; but it was only an appearance. Within his family he was a simple, open, kind and generous man.”

His daughter-in-law, Michèle, described him in a similar way: „He was extremely compassionate: he liked to give and share. He had a pleasant voice and a charming Hungarian accent; he was stylish, elegant, tall and handsome. He was fond of women and liked to court them; but at the same time his underlying temperament was distant. He was a humanist, longing for a more just world.”

And a third opinion from outside the family: „He was mesmerizingly kind and had a heart of gold. He made conversation pleasant and spirited. I keep many letters from him,” said Árpád Vígh, Doctor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, professor at the University of Pécs, writer and literary translator. Immediately following the fall of communism, Vígh served as director of the Hungarian Institute in Paris from 1991 to 1995, and as cultural adviser to the Hungarian Embassy in Paris. „Once, for example, I asked him to draw a new logo for the Hungarian Institute, so that the institute's program brochure would have the logo of a Hungarian artist, and he drew one up in a flash. His son Yvaral painted the big H in red, white and green.”

Vasarely and his wife Claire have always retained their Hungarian identity. „Győző and Bonzi became French citizens in 1961. I clearly remember my childhood, adolescence and youth. They always spoke Hungarian to each other. My grandfather often counted and wrote in Hungarian. It was important for them to preserve their Hungarian identity, even though they learned French very quickly and quickly attained an excellent level of proficiency. My uncle and father learned Hungarian in Budapest during the Second World War. André is very good at writing and speaking, while my father was good at speaking Hungarian. For their first wives – Barbara and Geneviève – this was not always easy, because they often switched to Hungarian at family dinners, especially when discussing certain topics.” According to some accounts, towards the end of his life, Vasarely's Alzheimer's disease made it difficult for him to remember what he had done the previous day, but he was still able to recall his childhood and Hungary perfectly. One of his favorite pastimes, especially towards the end of his life, was listening to Hungarian folk songs.

All of this can be found in the biography of Pierre Vasarely and his co-author Philippe Dana, published in 2019 under the title Vasarely Une saga dans le siècle [lit. Vasarely – A saga in the century], as well as many other details, both large and small, about the artist's everyday life. For example, that he was ahead of his time when it came to healthy living, that he ate exactly the same amount of plums every morning, and that he was persistent in his work. „He would ask for half a cup of coffee with half a sugar – it was half of everything with him,” recalls his daughter-in-law Michèle, who managed his affairs for many years, „I think it was also because he wanted to hold on to his pleasures, but he didn't want to overdo it. That's how he was with smoking too: every morning he would put three cigarettes in his pocket, and he would space them out for the whole day and smoke them at the same time of day. He would have liked to smoke more, but he didn't because he knew it wasn't healthy, only making an exception when he was being photographed. Then he would light up a cigarette because it was part of his image.”

Vasarely was an innovator in many ways. It was only relatively late, in his forties, that he found his own unique voice and delved into the world of optical illusions. He is considered the father of optical painting, i.e. op-art, and kinetic art. He became known for his paintings of pure forms in the language of geometric abstractions, which played with the perspective of the viewer, exploiting the uncertainty inherent in our visual perception. He also opened the door to future art movements, such as digital art.

His alma mater, the Workshop, (Műhely) known as the Hungarian Bauhaus, which he visited between 1929 and 1930, must have played a major role in his innovative approach. The Workshop was also where his theories on social art were rooted; he wanted to democratize art, as he was convinced that art belonged to everyone and should be accessible to even the lowest strata of society. „It is nobler to give to everyone than to keep everything for ourselves and our loved ones”, he wrote in 1972. This is why he wanted to make his art accessible to all: and why he decided to put much of his work on the market as cheap prints, and why he specifically designed his optical illusion sculptures to be seen on the streets. He was described as a communist, although at the time the term meant something different in France than it did in Hungary, and it would have been hard to find a French artist at the time who was not left leaning.

Op-art took off and Vasarely became a star of the sixties and seventies. His work appeared in fashion, clothing, interior design and many other fields. Before long, Vasarely could be found everywhere: the facade of the former RTL building on rue Bayard (now demolished), the Gare Montparnasse station in 1971, the dining room of the German Central Bank in Frankfurt, the cover of David Bowie's Space Oddity album, the Renault logo (in collaboration with Yvaral), the Taittinger champagne bottle, advertisements, TV shows. These are just a few examples of how much he defined his era.

In the 1980s his popularity began to decline rapidly, and following his death he and his work seemed to fade into obscurity. But op-art and geometric abstraction have recently been enjoying a resurgence, as evidenced by the fact that, although Vasarely's reputation was damaged by scandals, his works still generate the highest sales at auction of any late Hungarian artist. Most recently, for example, he surpassed Simon Hantai and László Moholy-Nagy. At the same time, the conflict between family members is raising concerns and uncertainty among collectors, which is also affecting auction prices. And this means that many collectors and potential buyers are cautious and prefer to wait and see what comes of the trench warfare.

The burning question at the moment is clearly whether the verdict of the final trial will bring an end to the decades-long feud, and whether the 112 works of art – which are currently languishing in the FBI's evidence collection in the Caribbean (presumably in a warehouse) – will make it back to France. Or will the works return to the Michèle Taburno-Vasarely Foundation? Or perhaps some unexpected turn of events will shake things up? As of the date of this article, no decision had been taken, which is in part why we sat down to talk to Michèle Taburno-Vasarely and Pierre Vasarely. You can read these interviews in the upcoming installments of this series.

As for possible scenarios, two of our sources agree that regardless of the outcome of the lawsuit, both foundations will be able to continue operating, since they operate in different legal and economic environments, subject to different conditions. For this reason, once the lawsuit is settled, in theory the works in the custody of either the French or the Puerto Rican foundations will no longer be able to change hands, as the foundations will operate as separate entities and will not be dependent on heirs, be they current or future members of Vasarely's family.

It remains an open question whether, after Michèle Vasarely's death, the collective rights manager, the French ADAGP, will acknowledge that the institution she founded can possess part of the reproduction rights. And there are many more questions surrounding the potential final outcome: will Pierre Vasarely be able to transfer the rights he inherited from his uncle André to his children? How can this inheritance be integrated into the legal structure of the Vasarely Foundation of Aix-en-Provence? Another not-so-minor issue is what role in all this chaos is played by the other grandson, Xavier Terlet – André Vasarely's alleged illegitimate child who recently came forward – who has so far refused to take part in the court case, as his personal peace of mind was more important to him than his involvement in legal matters. Some of the questions will only be addressed in the future, others in the interviews with our two protagonists, but as we have already said, it will likely be similar to standing in front of a Vasarely painting: it all depends on where you look at it from.