This year was vital, these three hundred children would have been lost without education if we hadn’t been able to open

We speak Ukrainian among ourselves, but everyone is learning Hungarian. I see that the others sometimes have difficulties, but we are making progress," a Ukrainian student tells us in Hungarian at the only Hungarian-Ukrainian bilingual school in Csepel. The school received its licence to operate after Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in Kyiv this year, which only took place after he had made several visits to Moscow. The school in Csepel, which had been in the making since the outbreak of the war, so for more than two years, could thus finally open. Serhiy and Olena felt it was their mission to create a school that would fit in with the Hungarian education system for the Ukrainian refugees who had arrived here.

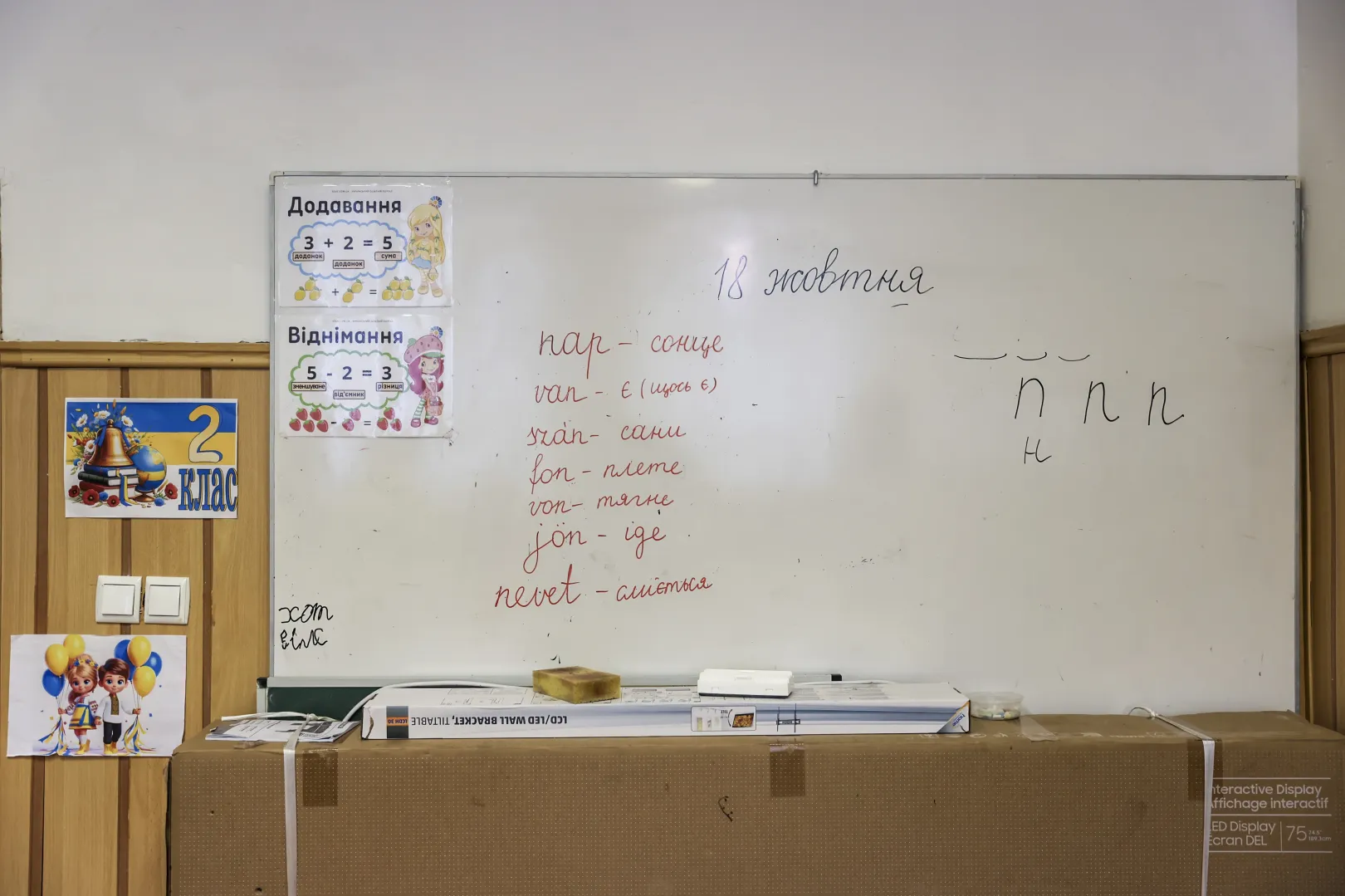

The school building has two floors. During recess, the lower primary children are running around the courtyard, while those in the upper primary spend time chatting upstairs. Each class from first to twelfth has its own classroom, decorated with posters made by the children and, in addition to Ukrainian and Hungarian textbooks, there are now also trophies: the school held a sports day a month ago, and the winners put the trophies on display. "At the end of the sports day, for example, we sang the Ukrainian national anthem together. And on 15 March (Hungarian national holiday – TN) we recited poems in Hungarian," says one of the students, explaining how they celebrate the events of both nations.

"Many people think that we decided to have a school in May and then it started. In reality, it took two years of constant work to make it happen," says Olena. Before they submitted the paperwork to get the permits on 31 May, not only did they have to have the plans in place, but they also had to have the teachers secured too. "But political will was definitely needed for us to get started. The school could not have launched without Orbán and Zelensky's meeting in Kyiv, but a lot of preliminary work was needed so there would be something to register after their agreement." Olena is referring to the July meeting between Orbán and Zelensky, where the two leaders agreed to establish a Ukrainian school in Hungary.

Olena and her husband, Serhiy, had been planning to set up a primary and secondary school for Ukrainian children, integrated into the Hungarian education system since 2017. The final push came after the beginning of Russia's war against Ukraine. "This was our dream, we wanted to have a school for Ukrainians living here," says Serhiy. They feel the importance of this themselves as they moved to Hungary from Kyiv 17 years ago with their teenage children because of Serhiy's business.

Later, both their children graduated and found work in Hungary. "Our son attended ninth grade three times, once in Ukraine and twice in Hungary, but he learned Hungarian. When people ask us how you can learn Hungarian, we use our children as an example. They are a testimony that it is possible".

It’s been an important year

They found a place for the Hungarian-Ukrainian Bilingual Primary School and Secondary School, which opened in September with 300 children and is accredited by the Hungarian authorities, in Csepel. Olena says they were lucky to find the building at the end of May because buildings which are suitable for a school are either occupied or in very poor condition – but here everything was provided.

The school is supported by grants, donations, and – as an official Hungarian school – also by normative funds received from the state budget. The Ukrainian state provides the school with textbooks and the Ukrainian Embassy also helps. Obviously, the district where the school is located is also adapting to the Ukrainian school: when we visit them, the first thing that catches our eye is the grocery store next to the school. "Snack bar menu", the sign says in Ukrainian too, listing the menus the children can buy from the shop during the day.

“This year was crucial. If we had not started, these three hundred children would also have been lost without education.

– Olena says. “We've had kids come here who studied online for five years, first because of Covid and then the war. They were asocial and had difficulty communicating. Some of them were in fifth grade when they first learned what an in-person class looks like.”

Not assimilating, but integrating

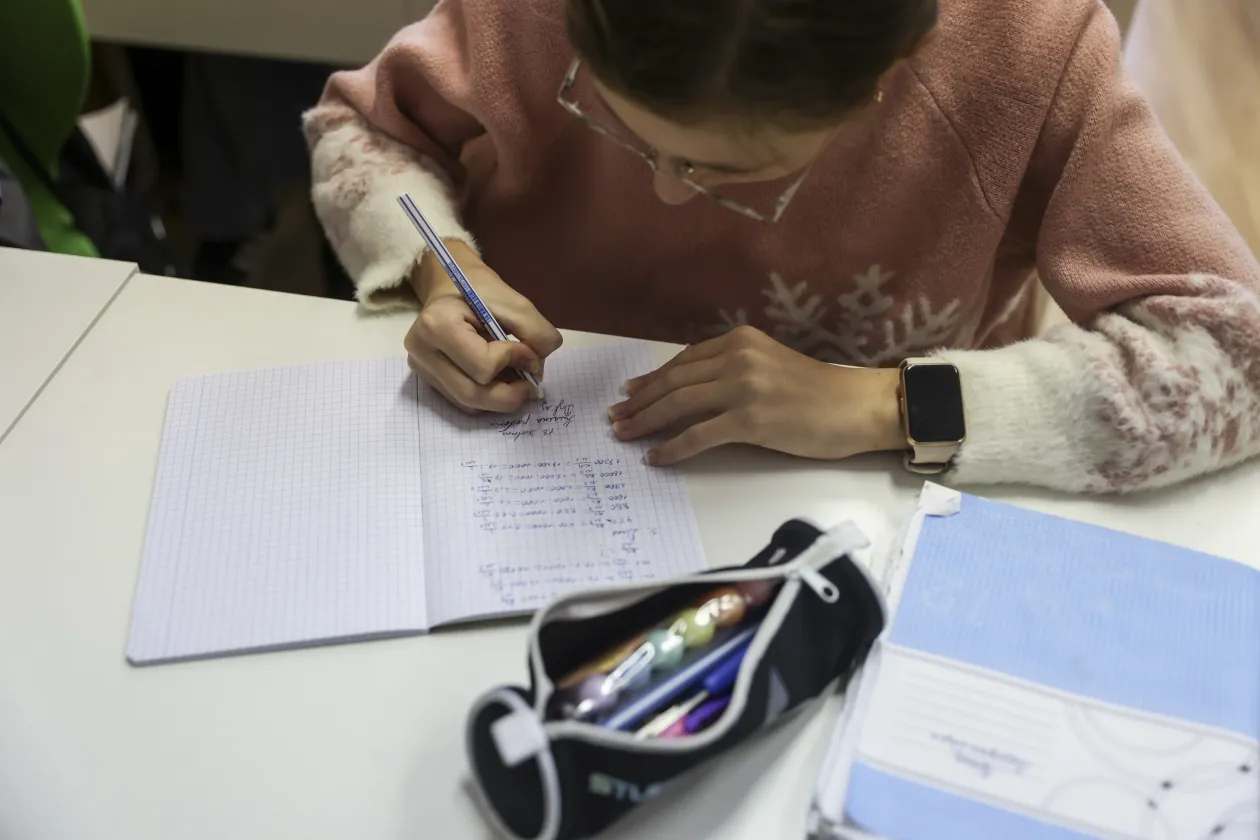

September was a big emotional rollercoaster at the school because of this. "The kids enjoyed having someone to talk to, they were happy, they were hugging, they had so much energy, and kept running around at break time," – but many children had to be brought up to age-appropriate levels after years of online education. "Some of them couldn't read or write well and had never learnt a poem, they didn't even know how to go about that," – Olena mentioned some of the difficulties.

But they noticed that the start of the school year was also difficult for those who had previously studied in Hungarian schools: the host schools were not always able to help them overcome language difficulties, as few teachers could speak both Ukrainian and Hungarian. "So, the child just sat in a foreign language environment and that was it, so many dropped out of school," says Olena. Another obstacle to children learning Hungarian in Hungarian schools is that they are afraid to speak the language because they are afraid of what the native speaker children will say about their Hungarian. As Olena puts it, "They likely would not have been judged, but the point is that if the child is afraid of that happening, it creates a serious obstacle for them speaking Hungarian".

There is no such danger in the school in Csepel, however. The focus is on the acquisition of Hungarian and thus helping integration. The children in lower primary are learning 60 percent of their subjects in Hungarian and 40 percent in Ukrainian. Mathematics and reading are taught in two languages, and from the fifth grade onwards, they start English as well. In the upper classes, they have more subjects in Ukrainian, while in secondary school, 30 per cent of their lessons are in Hungarian, and as in other bilingual or ethnic minority schools, Hungarian history is taught in Ukrainian, but from a Hungarian textbook. And in two years’ time, the school will also have to come up with textbooks in Ukrainian, for example, a history textbook that fits into the Hungarian curriculum. The school will also have students graduating at the end of this academic year. They will take their exams in Ukrainian and they can take an exam in Hungarian as a foreign language.

"Our goal is not assimilation, but integration. Some families may stay, some may eventually return home, but they need some knowledge to make a decision," Serhiy says about Ukrainian families who have come to Hungary. Parents, they say, play a big role in how the child is coping with difficulties, including how well he or she learns Hungarian.

If the mother decides to stay – as there are usually only mothers among the refugees – this decision supports the child's education. "But if the mother doesn't know where they will be in six months, the child is less motivated to learn, and the teacher can't do much about that," says Olena. However, if the mother feels comfortable in Hungary, “it provides an extra boost that, for example, it helped a pupil recite a poem in Hungarian at a 15 March celebration.”

But the language issue is actually even more complicated than that. Not all students have a clear background in Ukrainian. Before the war, it was common to speak dual Russian-Ukrainian or even a kind of mixed dialect, Surzhyk (a mixture of Russian and Ukrainian) at home.

“It's important for us to speak Ukrainian here, not just because of the war, but that is one of the factors. The language the child speaks will be the language he or she will think in.”

– says Olena. The school is mainly attended by children of parents for whom it is important that the child speaks Ukrainian. Olena and her husband make sure to call the parents' attention to this. It is the right school for the child if the parents are serious about Ukrainian being important for them.

The teachers are refugees too

Serhiy explains that in principle, the legal possibility for establishing the school existed before. He sees the Hungarian legislation as particularly generous in this respect, as 12 of the 13 officially recognized ethnic minorities have ethnic minority schools. "Hungary provides all the conditions, we just had to take advantage of the opportunity provided in the law," he says. "But until the war, nobody was really interested in it and neither did the financial resources exist to implement the plan," he adds.

Olena had already created the base of what would become a full-fledged 12-form primary school for 300 children before the war. She organised cultural events with the non-profit organisation House of Ukrainian Traditions to bring Ukrainians living here together and to bring them closer to Hungarians.

"Ukraine is a neighbouring country, but in Hungary, they know almost nothing about it, or at most they think of bad things, such as organised crime in the 1990s. We wanted to change this image, to prove that we have something to show, that we have Ukrainian traditions and history," Serhiy says. With the school, Serhiy and Olena wanted not only to bring Ukrainian culture to Hungary but also to show that "we like Hungarian culture, we like the Hungarian language. We are grateful for the opportunities this country gives us.”

In 2017, Olena, together with the Greek Catholic Church, set up a school for Ukrainian children which met on Saturdays. Starting in 2022, they also accommodated refugees. There was a time when they had 250 children attending. The couple invested their own money into the school but needed more to keep it running. They applied for grants wherever they could, and for nine months they were even supported by an American organisation. The Saturday school then became a five-day school, integrated into the Ukrainian system. They taught Hungarian in this school as well, to support the children’s integration. This served as the basis for the establishment of the school in Csepel.

"The teachers are all refugees here, so there are no male teachers," says Olena. The children receive both Ukrainian and Hungarian textbooks, depending on the subject. There are classes which are learning Hungarian history from a Hungarian textbook, but physics, for example, is taught from a Hungarian textbook in Ukrainian. Olena says that it's good because "even though the students take the school leaving exam in physics in Ukrainian, this solution is still useful for language learning". This way, by the end of their schooling, children will learn to use Hungarian, Ukrainian and English as well.

1956 and Ukrainian history

Several students have fathers and close relatives fighting, and there are both teachers and students who have already lost someone in the war. For this reason, the school also has two Ukrainian psychologists on staff: one for the lower and one for the upper classes. "The teachers also received training focused on war trauma. We have twelve children who have been through the most difficult experiences, they, along with their mothers, regularly meet with the psychologists on Saturdays," says Olena.

Some of the children have been to Hungary before, some have parents who have worked here before, and for them, Hungary was "a bit like coming home". We speak Hungarian better now," they say, but add that they would prefer to return home when the war is over. Most of the students came from the inner part of Ukraine, closer to the front, "some have talked about rockets, and about other things they had seen. But we’d rather not talk about the war anymore. We don't want to, because it's terrible," says one of the boys, who is now most anxious to win the election for president of the student council. "Chances are I'll win," he says with a smile.

The break is over, so the students get up and head back to study Hungarian history in Ukrainian. "We just talked about '56. I see that there are parallels between that and Ukraine in 2014. The Russians came in '56 and they are coming now, only in 2014, at first they didn’t come with tanks, but with political messages. And now they’re coming with tanks," one of them explains. Some students talk about how they used to speak Russian at home for a long time, but have now switched to Ukrainian there too, and that it is important for them to use that language. Some have close relatives living in Russia, but the war has separated them for good because people there think Russia was right to start the war. They also say that "all the teachers here understand us, that we need time, but we do want to catch up".

According to Olena some teachers are planning to return home once the war is over. "Until then, we are trying to support each other so that no one feels like they are in a foreign place," she adds. There are currently 33 teachers in the school, "Serjoy and I are in charge, it's our job to make everything work. The professional basis is provided by teachers who have been teaching for 20-25 years". Like the students, the teachers are also learning Hungarian. "They have to speak some Hungarian, this is a Hungarian school, and the online system for academic registration and records is also in Hungarian," says Olena. The director of the school is from a mixed Hungarian-Ukrainian heritage. Before she says goodbye, she also talks about how the war affects people in the school. "It is difficult to talk about it, there is no war without death. The teachers need help too, because they also have to carry the children’s burdens. But we must not forget that both the students and the teachers are human," she says.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!