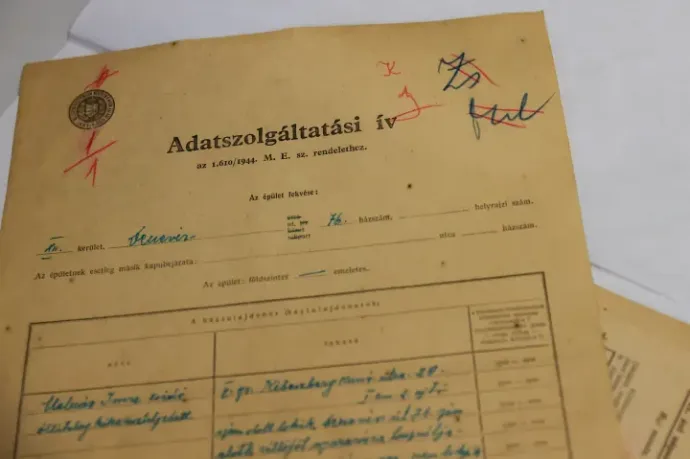

Documents dating back to 1944 were discovered hidden in an apartment located in a building near the Parliament earlier this year during the demolition of a wall.

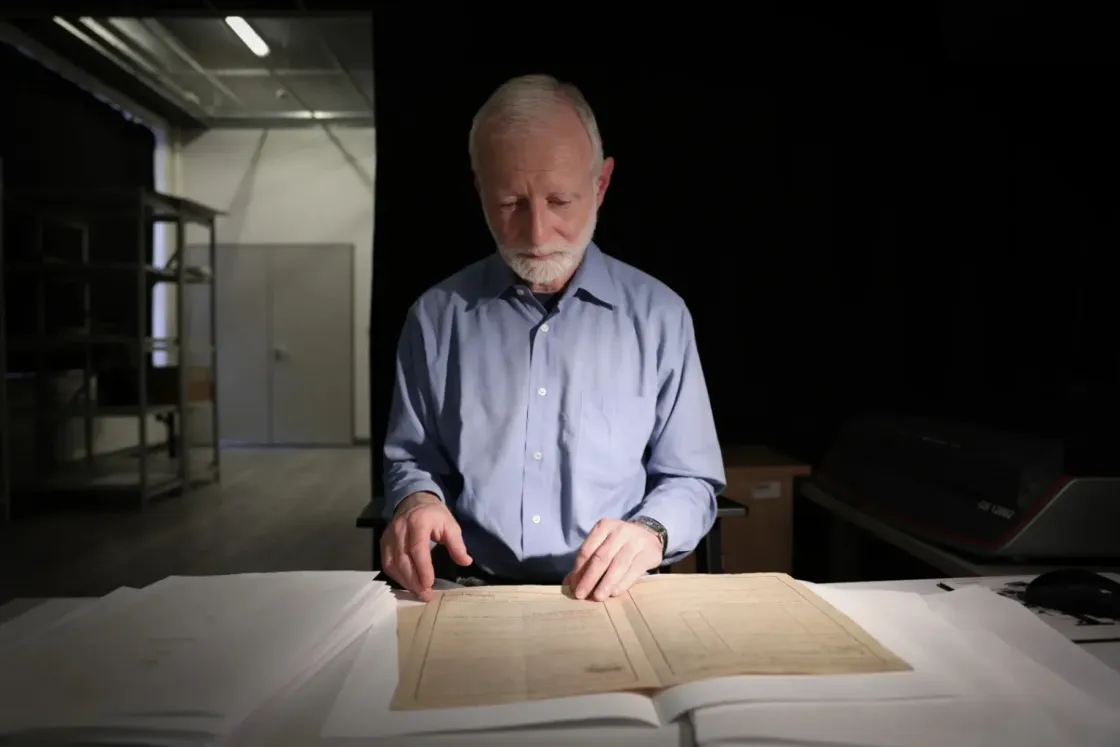

"We thought that nothing had survived. We believed that the Housing Authority records had been completely destroyed. The avalanche was triggered by a crack in 2015, when a fourth-floor apartment in one of the apartment buildings at Kossuth Lajos Square in Budapest was being renovated and data sheets from 1944 were found behind one of the walls," András Sipos, historian and department head at the Budapest City Archives, said at a press conference on 16 April, the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Hungarian Holocaust. The Municipality of Budapest and the Budapest City Archives held the joint press conference on account of more documents from the years immediately following the German occupation of the city having been found in the same apartment building in early 2024.

Mayor Gergely Karácsony also spoke at the event, saying that these documents and the stories they contain function as a "microscope" through which we can gain insight into the history of Budapest during a time of hardship and horror

They suspected there might be more valuable documents hidden in the house

As mentioned above, documents dating back to the German occupation had already been found in the building nine years ago. At that time, 7019 data sheets were found behind a wall when a fourth-floor apartment was undergoing renovation. The discovered sheets were the ones based on which "the yellow star houses" to which Jewish families were forcibly moved were designated. In 2015, both local and international press reported on the sensational discovery. According to András Sipos, even then it was suspected that there might be more valuable documents hidden in the house.

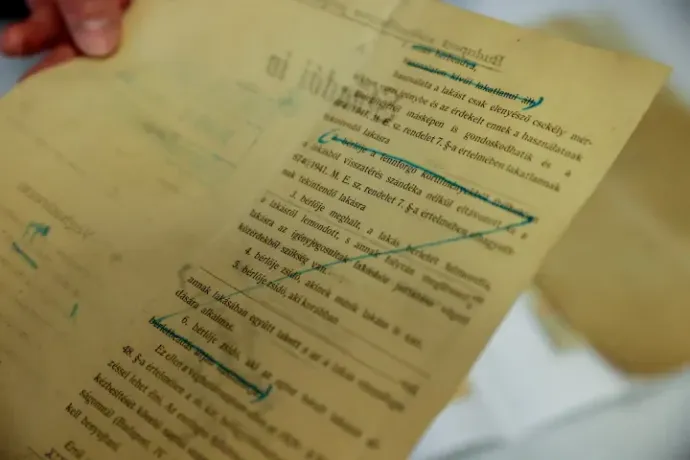

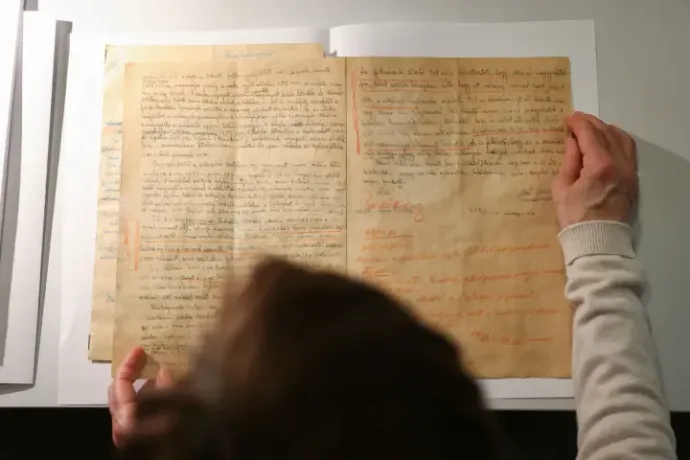

The historian previously told Telex that the newly uncovered documents were discovered at the end of January, when an unnecessary wall in the hallway of an apartment currently under renovation was demolished. Sipos explained that the documents, both those discovered now and those found in 2015, came from the office of the Government Commissioner for Housing in Budapest and the surrounding area, which was set up in July 1944, and said that they reveal what kind of cases were handled by the office on a daily basis, what routine procedures were followed, what forms were used, as well as

the fierce struggle that went on for housing in the capital during the Hungarian Holocaust.

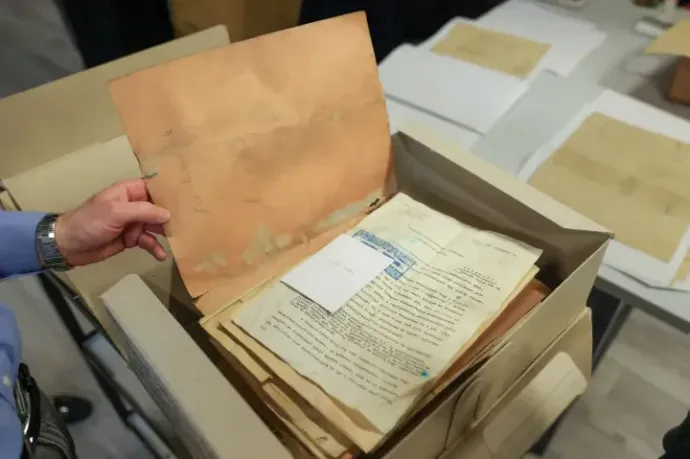

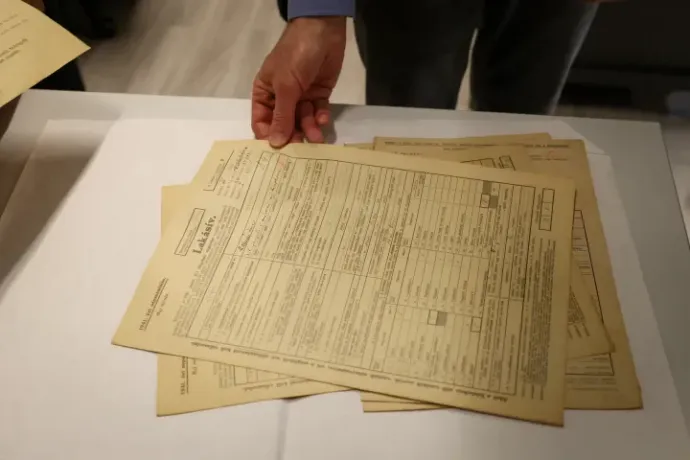

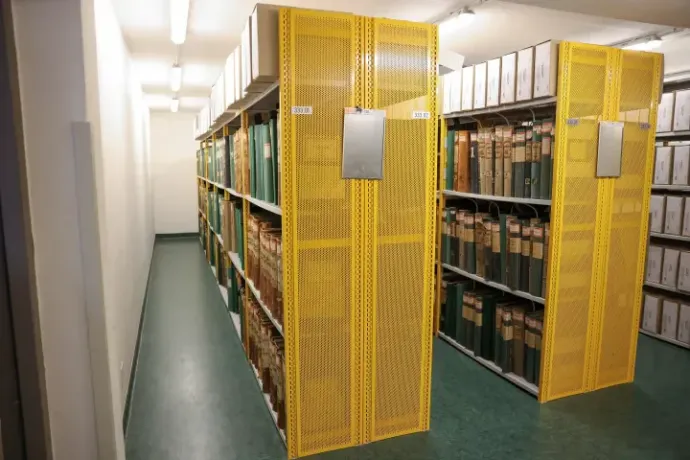

The documents found when the wall was demolished were gathered into three 14-centimetre-high boxes, and were first subjected to a special disinfection process because they were considered to be contaminated with mould. The papers were then taken to the archives' conservators, who cleaned and flattened them so that they could be scanned in good quality.

As it turned out, even more material was discovered in the spring: at least twice the volume of the first batch of documents was discovered behind a partition wall during an electrical installation in March.

But why is it that, for the second time, valuable documents have been found in the same apartment block? "After the Jews had been moved out, many of the spacious apartments in the building became vacant and were used as offices by the aforementioned Housing Commissioner's office," András Sipos said.

Anyone could pick an apartment and submit an application to the office

Eighty years ago, due to the gradual introduction of the "fixed housing regime" during the war, it was not possible to rent or lease freely in the Hungarian capital. As of 9 July, the Office of the Government Commissioner for Housing was in charge of deciding the fate of all residential properties in Budapest, including those left vacant by Jews who had been moved to yellow star houses. "Among other things, the Government Commissioner for Housing – who was under the Ministry of Interior – was authorized to appoint new tenants. If someone wanted to rent an apartment, they could only do it if the officials determined that they were entitled to do so," explains András Sipos.

A certain villa in Denevér street in the XII district, which was already listed on the data sheets found in 2015 is a good example. The recently discovered documents, which include a letter from a gardener reveal interesting details about the history of the villa.

"The owner of the summer home was the director of a company, who was originally Jewish but had converted to Christianity. He lived in the street called Klebelsberg Kunó (today's Hold). The building also included an apartment for servants, which is where the gardener who sent a letter to the office of the Government Commissioner in July 1944 was living. In his letter, he explained that after the German occupation, the villa had been rented by a lieutenant who lived in the same house as the owner.

The gardener claimed it was a sham rental, while the lieutenant's mother said that the Jewish owner no longer had any belongings there, since they, as tenants, had bought the furniture from him, and that the villa had been rented before the occupation. The lieutenant presumably did this so that no one could claim the house and no Germans could move in. The gardener also sought to have the Government Commissioner's office cut off a one-room apartment in the villa for him so he could move over from the servants' quarters."

The documents also reveal that the office had its own investigators help in solving these cases. "This was also news to us. The reports found in the wall clearly indicate that in each case the office sent its own detectives to investigate. This is what they did in the case of the villa on Denevér street too. The investigators’ detailed report also includes the gardener's testimony," Sipos says, adding that the documents also show how serious the housing situation was at the time.

"The application of an official, sent to the office in January 1944, has also turned up. In it he states that he is living in a damp shop with his two children, that everything keeps getting wet and that his children are constantly falling ill. He describes himself as a corporate officer with a good salary. This means that he was able to afford a better flat. It's not that he had financial problems, it's just that they had no place to go.

The reason he approached the office was because he was told that there was an apartment in the house where he was staying that might be good for them. The tenant of the property was staying with his father, and only came by occasionally to look around."

According to the historian, this is a good illustration of how things worked at the time.

One could simply pick out an apartment and then submit an application to the authority, hoping that after an inspection and a check of their documents, the place would be allocated to them.

This is also evidenced by another recently discovered housing application, the writer of which considered the place where they lived to be small. They asked the authority to allow them to move into the flat next door. "It says that the flat was vacant after the Jewish family living there had to move out," the historian explains.

Why was the housing situation at the time so difficult?

Nowadays there are many empty flats all over Budapest which remain unoccupied for years, because most people cannot afford to buy or rent property for exorbitant sums. Eighty years ago, there were no flats available to rent, so even those who could have afforded to rent one could not find one.

"During the years of the war, the already dire housing situation worsened rapidly as tens of thousands more people arrived in the capital because of the war industry boom and the jobs available.

The city's population peaked on the eve of the German invasion at around 1 million 380,000. Regular bombing began in April 1944, and although many people left the city, it still became increasingly overcrowded. In addition, those who had to find a new home because the house they had been living in had been hit by bombs also had to be relocated," András Sipos explains.

Hiding the documents was likely an organized operation

As mentioned in a 2015 Index article, there are several theories as to who hid the documents in the walls of the Housing Authority's offices and why. According to András Sipos, the documents found at the end of January and their location suggest that the papers were not used as insulation between apartments. The idea that the tenants of the apartment building wanted to somehow get rid of the documents can also be ruled out.

"Since the documents were hidden in the same exact way in different apartments far apart from each other, there is no doubt that this was an organized effort linked to the government's Housing Authority. As to why the documents were hidden, that remains a mystery to this day."

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!