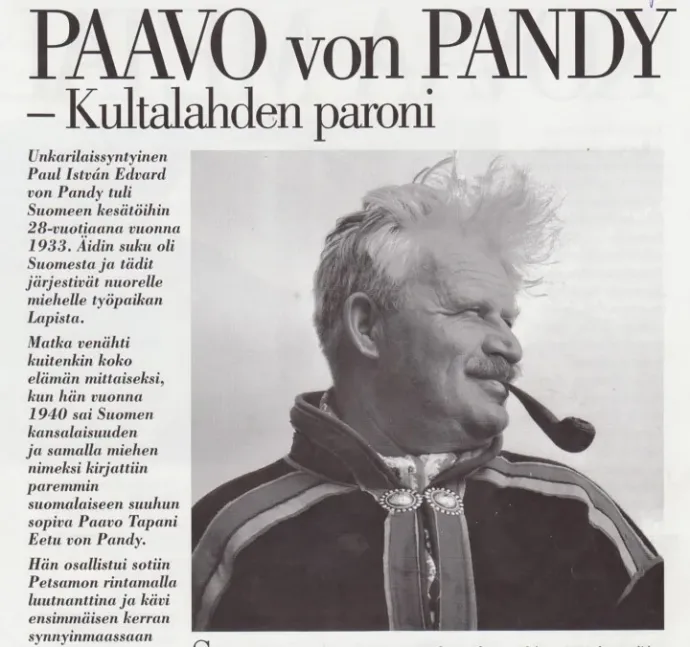

His father was the eponymous chief physician of a hospital, his mother the daughter of the first Finnish ambassador to Berlin. He went missing at the age of 15, was a Finnish-German soldier at 35, and then spent twenty years traveling the world, giving over a thousand lectures on Lapland. The life of Pál Pándy, aka Paavo von Pandy, is anything but ordinary.

Arcanum Digitális Tudománytár (Arcanum Digital Library) is Hungary's biggest press database, where you can search and browse through tens of millions of pages of newspapers and magazines from the past centuries, whether daily or weekly newspapers, sports magazines or women's magazines. This article is largely based on Arcanum's processed and searchable sources.

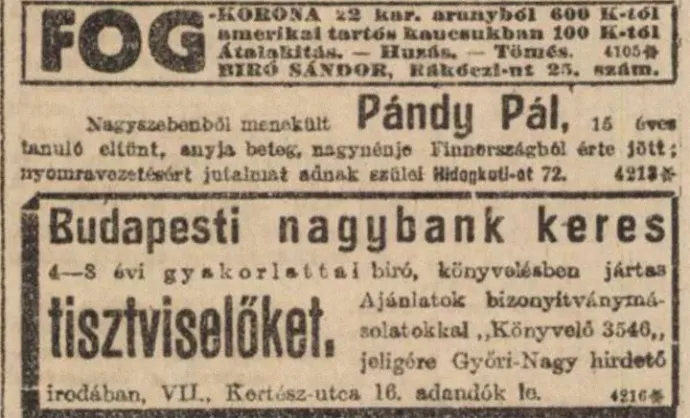

Pál Pándy, a 15-year-old student has disappeared from Sibiu and is missing, his mother is ill, his aunt came from Finland to pick him up; his parents have offered a reward for information leading to his whereabouts" – this short notice appeared in Pesti Hírlap in November 1920. The next news about this Pál Pándy took 23 years to arrive, as this is when his name appears in a report from Lapland in Finland in the 15 January 1943 issue of Magyar Nemzet:

Back at the "Pohjanhovi" hotel in Rovaniemi, a Finnish military officer approaches me.

– "I apologize," he says in Hungarian, "I have just found out that there is a Hungarian guest in the hotel.

– Are you Hungarian? – I ask, examining the Finnish uniform he's wearing, covered with medals.

– My father is Hungarian, but my mother was Finnish, and I am now in the Finnish army. I came to Finland a few years ago.

The editorial staff of the Rovaniemi newspaper hosted a lunch at the hotel that day, and we took Pál Pándy with us. We were especially delighted to hear his excellent Hungarian – he had lived in Transylvania for many years. His half-brother is the chief engineer of Hangya in Budapest, and his brother, Kálmán Pándy is the press attache of the Hungarian Embassy in Stockholm.

The comment about him "having lived in Transylvania for a long time" makes it clear that it's the same Pál Pándy (we also found information on a Pándy Pál from Budapest in Arcanum, who was very active in the scouting movement in the 1920s and 1930s). Linguist György Fodor’s study, published in Finnugor Világ in March 2021, and some newspaper articles about Pándy in Arcanum reveal quite a career.

Pál Pándy was born in Gyula in 1905, and his father, originally from Békés County, was a prominent neurologist of the first half of the 20th century, and made his mark in the field of laboratory diagnostics. He also met his future wife thanks to his professional career: he studied Swedish mental health care in Stockholm in 1903, after the death of his first wife, Anna Izabella Dömötör in 1902. Aino Maria Edvardintytär Hjelt, a twenty-year-old Finnish nurse was a nursing student at the same place. And it's really just a side note that she was the daughter of Edvard Hjelt, Finland's first ambassador to Berlin. They married in 1904, while still in Helsinki, but then moved to Hungary, which is where the Pándy children – four boys in all – were born. Pál was the oldest, born the year after the wedding.

His father, Kálmán Pándy became department head at the Lipótmező mental hospital in 1905, and from 1911 he was director of the State Mental Hospital in Sibiu, Transylvania, for eight years. He didn’t visit Finland often, but his wife and their children spent their summers in Tuusula, Finland, at the lakeside home of Finnish relatives (about 30 kilometers from Helsinki).

This environmental diversity, unusual for the time, may have been one of the reasons why Pál Pándy, who inherited the title of baron from his father, not only became a true polymath – he studied horticulture and political science before joining the border service – but also mastered several languages, and by the middle of his life was fluent in eight (in addition to Hungarian and Finnish, he learned Swedish, English, French, Italian, Spanish and Romanian). He most likely learnt the latter out of necessity, following the changing borders after the First World War (when – as a result of the Trianon peace treaty – Hungary lost a big part of its territory to Romania -TN). Although in 1919, the family was already living in Budapest, as his father had first gotten a job at the Ministry of Public Welfare and then at the rehabilitation center for former alcoholics in Rákoskeresztúr.

I haven't been able to find clues as to why and for how long the then 15-year- old Pál "disappeared" in 1920, nor about when and under what circumstances he turned up. It was 1920 though, the borders of the state have just been redrawn, the former idyllic life in Sibiu was a thing of the past, and for a teenage boy, this change – a significant part of his childhood suddenly becoming nothing – must have been a major break. Pándy never completely got over this, at least according to György Fodor's previously mentioned study, which talks about him leaving Hungary in 1931 and adds that 'from then on he was mainly to be found in Finland'. In 1934 he bought a property in Ulkuniemi in Lapland, but it was not until 1936 that he settled there permanently, on the shores of Lake Inari, not far from the Arctic Circle. So instead of choosing to live close to his mother's family, he chose Lake Inari, which is about 900 kilometers north of Helsinki.

It was here that the Magyar Nemzet journalist encountered him during his visit in 1943. The Second World War was ongoing, and Finland was fighting against the Soviet Union and for its independence at the time. Pándy, who was married by then, started working in a country house, then set up an inn in Virtaniemi, and had a special reputation for being able to direct tourists from all over the world in their native language. At the end of 1939, during the Winter War, he joined the Finnish army as a volunteer (he spent his military years mainly as a German-Finnish interpreter until the end of 1944). In early 1941, he was granted the coveted Finnish citizenship, which he had not received before, despite his origins. After Hitler's troops left Lapland, Pándy returned home and had the foresight to destroy all traces of his military service in the war – thus surviving the Red Army's settlement not only in his neighbourhood but also directly at his farm.

By the 1950s, he had established a model farm here. By this time he had long adopted all the local manners and customs, wearing traditional Sami clothing, smoking Sami pipes, fishing, hunting, raising reindeer and goats, growing potatoes, turnips, horseradish, asparagus, spinach and even peppers near the Arctic Circle. He remarried in 1951 – it is not known when he lost his first wife – and later had three children with Klaudia Lauronen, also a Finn: first they had two boys, Jorma and Mikko, and then a daughter, Annikki Maari, named after his mother.

Until 1970, there was no mention in the Hungarian media of the Hungarian nobleman, who had moved north and slowly became a Sami, and who, according to the records, never boasted of his noble origin. The first time he was mentioned was a single sentence in "Élet és Tudomány" (Life and Science) magazine: "During my visit there I heard about an eccentric Hungarian with an adventurous past named Pál Pándy, who had settled down permanently on the shore of a fabulous, remote bay of Lake Inari thirty years ago and has since then continued his life as an "honorary Laplander", dividing his time between his library and his reindeer". And in 1970, in the 18 April issue of the weekend appendix of Magyar Hírlap, a major feature on him appeared under the title A Hungarian Robinson, with the subtitle: A blooming garden beyond the Arctic Circle, with drawings by the author, Lajos Vincze (at the time there were no photos in the paper, only hand-drawn illustrations).

The article talks about why he left Hungary in the 1930’s, and it also explains that he doesn’t only manage his farm, but spends a lot of time advertising Lapland internationally. The answer to the first question is: “I left Hungary in the 1930’s as a freshly graduated lieutenant of the Military Academy. I originally came here to visit my Finnish grandmother.

It slowly, unassumingly dawned on me how impressed I was by the Finnish perspective and the humane way of evaluating things. I found the simple purity of it infusing my being, and by the time my holiday was over, my whole being was already in a state of rebellion. My life at home, in Hungary seemed a meaningless, suffocating cage full of shackles, my so-called vocation an unbearable mistake.

My father was a progressive, highly respected doctor. He understood that my rebellion was unbreakable and final. All he asked was: what are you going to do to start this "new" thing, son? It was a tough question. I will go out and prove that more than lichen can grow in the most miserable soil of the continent – I answered."

Pándy, who gave the author the impression of a "well-groomed Dutch gentleman enjoying a holiday in a fine robe and slippers", was, according to the article, at this time " working to prove the future of Lapland in Vienna, Hamburg, Switzerland, London, Prague. He spoke at colleges and universities and regularly welcomed scholars from Europe and overseas in his home in Lapland."

The same was reported by Korunk magazine in 1984, when it wrote of Pandy, then 80 years old, and his wife, ten years younger than him, that "the two seniors are old only because we call them old on the basis of their achievements, because they are otherwise living the same life as fifty years ago, only at a slightly slower pace. Pál Pándy was still chairing "Lapland consultations" at universities in Switzerland, Germany, Austria and Italy a few years ago, and he is still part of the world's intellectual bloodstream."

When tourists began to visit in greater numbers in the 1950s, Pándy said that his "German friendships made during the war came to life", and visitors could learn about everyday life in Lapland in German. 'The charismatic man, who told delightful stories, wore Lapland clothes and had a naturally easy-going manner, quickly won the hearts of the tourists', and not only did he speak many languages, but he was also very good at telling stories. "An entry in the guest book describes Paavo von Pandy, then in his mid-life, as 'a Hemingway character ready for Hollywood'."

It was during that time, through talking to tourists that he saw the growing interest and realized how little people knew about Lapland. So from the second half of the 1950s until 1978 he became a kind of traveling ambassador for the area, giving 1 027 lectures in almost twenty years in many countries around the world. He lived on his famous farm until 1984, and moved to the town of Nellim for the last two years of his life with his wife.

He had truly become a traveling ambassador and unofficial diplomat for Samiland – even the Finnish papers have referred to him as "The ambassador of Lapland" on several occasions. Indeed, according to a study referred to several times, Paavo von Pandy even received votes in the 'Lapps of the Century' poll. Along with all this, the family has also kept Hungarian traditions alive. In 2017, when Aamulehti magazine did a major report on the family, their daughter Annikki prepared goulash for the Finnish journalist.

If you enjoyed this article, and want to make sure not to miss similar ones in the future, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!