'After we closed for the day, there was a knock on the door, I opened it, and there stood a thousand migrants'

As we tread in fresh tire tracks through a field, we pass a sleeping bag and several empty Serbian mineral water bottles that had been left behind, then cut through the woods along the Ipel river. It's clear that several people have already trudged the route ahead of us. Although I am trying to shield myself, my hands get stung by nettles and my shoes get muddy, but we finally reach a very wobbly wooden bridge. We nevertheless walk over it and are now in Slovakia.

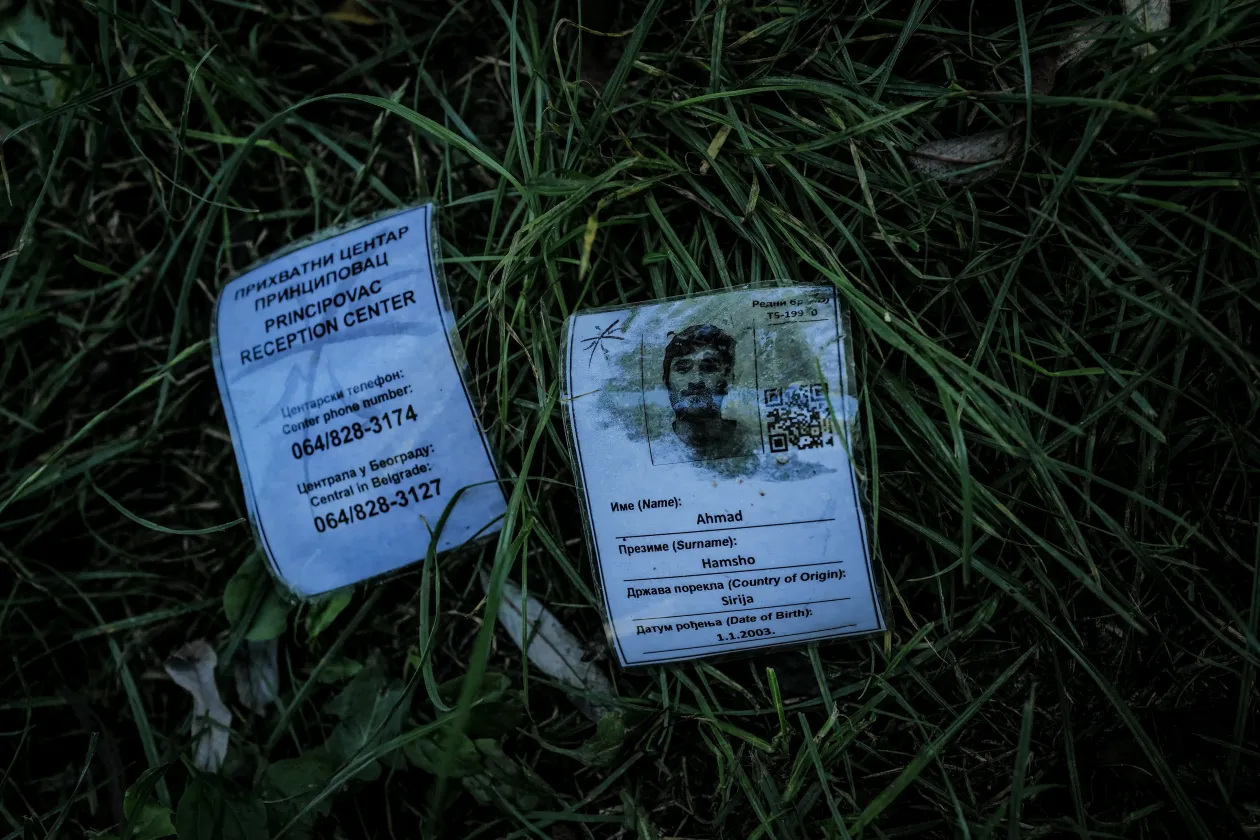

We spot sloppily discarded chocolate wrappers and some clothes scattered in the grass, and right next to them two identity documments issued in Serbian to the names of Mohammad Ahmad, born 1 January 2004, country of origin Syria, and Ahmad Hamsho, born 1 January 2003, country of origin Syria.

We are in southern Slovakia, in the border village of Ipel'ské Predmostie, one of the villages along the border with Hungary, where migrants have been arriving illegally in droves in recent weeks. It started around the spring, but then in the summer they started pouring into Slovak border villages steadily, with the country's technocrat government now putting their figures at several thousand a week. Most of them end up in and around the villages on the banks of the Ipel river: if they don't use the bridges, they simply wade across the shallow river. This is why a state of emergency was recently declared in the district.

Some Slovak parties say that Hungarian police deliberately refrain from stopping suspicious vans, and that this is how Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán intends to influence the upcoming Slovak elections. The current situation with migration and Hungary's recent release of 1,400 people smugglers from its prisons have already prompted the Slovak head of state to want to talk to Hungarian President Katalin Novák.

We cross to Ipel'ské Predmostie from Drégelypalánk on the Hungarian side, where a proper bridge is being built next to the wooden bridge. "They use both the wooden bridge and the new one, still under construction foring cross. Two weeks ago they caught people smugglers here who had been wanted for some time. The migrants jumped out of their cars at the bridge. Sure, it's bad for them, but it's worse for us because they're harassing the locals. I read it on Facebook," two women pushing a stroller outside a shop in Drégelypalank tell us.

"They come here in groups every day. Sometimes they have newborns with them. Whenever the police come, we know it's because they're here. My question is: how do they have money for this? Don't they have jobs? I don't understand" – a resident of Hont, a few kilometres away throws up his hands as he retreats into the shade of his gate. "Such is the world we live in. We'll end up wishing for the Kádár (Hungary's communist-era leader – TN) regime to come back," an elderly woman sitting under a tree joins in the conversation. "It's mostly old people who live here. And women are more easily hurt, aren't they? Anything could happen, we just don't know".

It is immediately clear in both Hungarian villages that people are afraid when they see the foreigners travelling in groups, although they add that they have not had any atrocities with these people so far, because they are just passing through the settlements and their surrounding area, they have no intention of staying here. They only have one goal: to cross into Slovakia without being busted by the Hungarian police. What awaits them – or has awaited them until recently – across the border is the "certificate of residence in Slovakia", which has been mandatorily issued for them. They are expecting this document to allow them to stay in the Schengen area.

When the dog barks, they know they're here

Ipel'ské Predmostie is a small village of about 600 people in Slovakia. This is where the wobbly wooden bridge that we also used to easily cross from one country to the other leads. Just a few hundred metres away there are already houses. As we arrive, a woman comes out of one of them to feed her sheep, which are penned up on the roadside. She tells us that migrants come here at night or at dawn, and they know this because that's when the dog barks. They just pass in front of their house and then go to the bus stop. They come in groups of twenty or thirty, mostly young men, and there is usually a woman and a child with them as well, she says, adding that they are scared, and don't dare go out in the evenings any more.

There were only two of them when the strangers first showed up in the village in April. Then two more came, and finally they started coming in bigger and bigger groups. "I don't know if those first ones were the guinea pigs, but after them, the groups started coming more and more often,"the mayor, Viktor Lestyánszky says. We were there on a Thursday, but they had a larger group come through the day before. "They had a mobile phone, I assume it had some kind of map on it, and the planned route was marked out for them. They are well prepared by the way, at least they certainly don't seem like they have no knowledge of the situation. We can't even be sure whether the person holding a mobile phone hasn't been here before," he says. The day after our visit, on Friday, there were four groups, totaling around a hundred more, and on Saturday a group of children came through: there were fifteen of them, aged between seven and fifteen, with one adult leader.

The mayor says the migrants have money, they go to the village shop to buy things, but he says it is impossible to travel thousands of kilometres without it anyways. "At the same time, we know that those who help them are not doing it for free. You know what I'm talking about". So they do have money, but no papers. They get rid of those along the way.

And what do they say about themselves? That they are all from Syria. And because it is a country at war, under international law they cannot be deported back there, the mayor explains, adding that each group of arrivals wants the same thing: to have the Slovak police called on them. That is why they are no longer hiding on the Slovak side at all. And the police have to organise buses to take them from the villages, so that the authorities can then start arranging for them to get the residence certificates they expect redemption from. They don't want to stay in Slovakia anyway, it's just a transit country for them, their final destination is Germany, he says.

"I'm often criticised for being too open and pro-migrant. This was never true. But I do believe that if any of us were dropped off in Syria, we would give all we have to get out of there. There are two sides to every coin. This one may even have more. One is that we should try to be humane and consider the fact that somebody really did take a risk to get here from Syria thousands of kilometres away. Two weeks ago, there was a mother here with a tiny baby who was around 8-10 months old. That's not something a normal person would do, to embark on such a journey with the infinite uncertainty of whether they'll be able to feed and nourish their baby. I doubt it's even possible for a mother to continue breastfeeding under such stressful circumstances. It's either a case of utter desperation or madness on her part," says the mayor, as tears well up in his eyes. “And the other thing is, what if one bumps into such a group at, I don't know, five in the morning in complete darkness? What do we assume about them? There's been no atrocity here, but things do pop into one's head. One of my acquaintances says he bought pepper spray for his wife. That's also a natural reaction. It’s a very complex issue.”

The mayor of Ipel'ské Predmostie has set up a kind of crisis committee with the heads of the other affected villages. Some of the other Slovak villages where illegal migrants have been arriving in droves from the direction of Hungary in recent weeks are Vel'ká Čalomijca, Koláre, Lesenice and Vrbovka.

In just three weeks, a total of four hundred and twenty people arrived in Lesenice, which has a population of five hundred. The first group went straight to the football field, allegedly because they could hide from the rain, mayor László Majdán explains in his office, adding that they likely pass the wire to each other along the way, because those who came after them automatically went to the field. There is water to drink and showers, and they can also use the toilet. "Then, of course, it's happened that some of them left their underwear, socks and diapers behind, which the local authorities then had to clean up. Once they even built a fire in the middle of the outdoor, but covered, stage."

"It was the first of September. After we had closed for the day, around two in the morning, there was a knock on the door. I opened it, and there stood a thousand migrants. But I didn't let them in," Vivien, who works behind the bar in a local pub says, perhaps exaggerating the numbers a little. A boar skin is stretched out on the green wall by our heads. Meanwhile Katka, who was also there that night, enters, saying they were both scared and didn't dare go home alone. One of them had seen a video on Facebook of what she thought was a migrant chasing someone in the street. She doesn’t know where exactly the video was taken, but believes it was in Slovakia.

The next moment they grab something from under the counter. "The axe isn't here to beat migrants with, but I went home with it that day. What am I supposed to do if the lights in my street go out? – Katka wonders. Vivien was escorted home that night by a male friend. They say that the foreigners are much more likely to speak to them when they are not accompanied by a policeman or when they are in a large group

After a while, the mayor got tired of the fact that "the state didn't care about us, they weren't doing anything, all they were thinking about was the elections. So we all met up there, in Ipel'ské Predmostie to have a talk. We all shared about our problems, but didn't come up with anything.” So he called up four or five TV channels to go out there. "Until then, there was nothing on TV or in the media, not a word about the migrants. The next day, the politicians started calling us, they came down to see us, they even invited me to Bratislava, and I had to make a statement on live television," says the mayor, with a photo of Slovak President Zuzana Čaputová hanging on the wall behind him.

In agreement with the others, he says that the people coming to Lesenice are not malicious, they just want the police, who sometimes take a long time to get there. "It's quite a big district, it's quite spread out territorially. It's happened before that I called them at 7 in the morning and they got here at 2:30 in the afternoon. And then they still need to compile the data, the names. That's also totally ridiculous. Everybody's birthday is on 1 January, only the year changes: 2007, 2004, 2005. And then there are the names: every third one is Ali and Ahmad. At one time, out of 179 of them, 35 were named Ahmad, and 40 were named Ali," he says.

Referring to the Slovak police chief, Majdán adds that the police have identified two terrorists and three people wanted for murder among those who had turned up in the area. "So we are afraid. They went to the shop, they paid with 50, 100 euro notes, they cleaned out the shop, they bought bread, rolls, cigarettes. There were twenty-five of them, so the women working there weren't exactly happy that so many of them went in". But the mayor says that since he was interviewed on TV a few days ago, they have avoided coming through Lesenice for some reason.

They still go to nearby Koláre, however, when the Ipel's water level is low enough, because that's the only way to get to the village. About 250 people live here, and there were times when 150 people came at once, other times there were 120 of them, and before that ninety-two. Thirty people had arrived the day before we were there, and they looked for the building with the flags to find the mayor's office, where they were seated on the grass in the yard, the mayor, Renáta Keresteš tells us.

At least 250 people have so far arrived in the neighbouring village of Vel'ká Čalomijca, where they herded them together on the football pitch. "But the biggest problem is that the locals are scared because it's an unfamiliar thing, and people aren't sure what to think. It's a strange feeling when you have 576 villagers and then several hundred migrants arrive. We are truly Christians, we try to help with the little bit we can, they are human beings after all. People have mixed feelings, you know, there's no denying it. We go out to the village and around the dam in the evenings to see if there's any movement," mayor Roman Pásztor says, describing local life.

They're all Syrians and they're all heading to Germany

As we go from village to village along the border, we hear that a bigger group of migrants has just arrived in the village of Kiarov, half an hour away, and they haven't all been taken away by the police bus yet. We hurry over to talk to them, and find sixteen of them sitting in the shade of a wooden monkey bar and slide, with a police car with two grumpy policemen a few metres away. As we step up to the vehicle, they roll down the window, and as soon as we tell them who we are, they roll it back up.

Of the sixteen people, one is a woman, three are children, the rest are young men. One of them speaks some English, he says they are from Syria. All of you? – I ask. Yes, he replies. He says they left four months ago and walked to Slovakia. Did you have any help? No, nothing, we were just looking at the map on the phone, he replies. They have no documents, they say. A few metres away, I find a document on the ground, also issued in Serbia, the same as the one from the wooden bridge, but they say it's not theirs.

Where do you want to go? To Germany. Why? "Germany no war". I tell them that there is also no war in Slovakia, or even in Hungary, to which one of the little children interjects: they have family waiting for them there. And why did they ask for help in Slovakia? Because the police are nice here, the man replies. "In Hungary, back to Serbia, in Serbia, back to Turkey", he says, admitting that they come to Slovakia because if they were caught by the police in Hungary, without the proper papers, they would be forced back to Serbia (According to the European Court of Justice, Hungary has violated its EU obligations with these asylum rules). In Slovakia, however, the laws are different – at least, they believe they can move freely within the Schengen zone with the residence document issued there.

The man says he doesn't know what will happen to them. The practice is that a bus picks them up and takes them to a collection point. Until Thursday, this was in Vel'ky Krtiš, about half an hour away, in a compound on the outskirts of the town, along some out of use railway tracks. We decide to drive there ourselves, but there are two policemen blocking our way at the fence. We aren't allowed inside, we can only take a few photos from the outside, and they tell us they can't give us any information.

Napunk had earlier reported that the Slovak Interior Ministry rented the premises from a company at the end of August without consulting the city council or without the hall being equipped to serve as a temporary residence for immigrants. Even the town's mayor, for example, only found out about the situation on his return from a holiday in Croatia.

Several people told us that about 800 people were crammed into the concrete compound without showers and water, and only a few mobile toilets set up along the walls. This caused discontent, and some have even escaped by cutting through the wire fence.

"About 10 of them escaped, they were running back and forth through here, some even got as far as the post office in town, but the police caught them in the end," two women playing with children by the side of a nearby apartment block tell us. They also say that while their daily lives have not been disrupted by the establishment of a makeshift camp in their immediate vicinity, they are still afraid for their children. Not far from them, an older woman is walking with her daughter, so we approach them to ask them about the camp. The younger one starts to shush us, and sends her mother a little further ahead: she then falls back, saying that although her mother knows that there is such a camp in the city, they didn't tell her how close it was, practically next to the apartment blocks. But she says they haven't sensed much of what's going on in Vel'ky Krtiš, and that it hasn't disrupted their lives.

The mayor of Lesenice, on the other hand, tells us that the locals of the town have 'rebelled', they even signed a petition saying that they don't want this place here. As a consequence, the place is now being dismantled and the people who've been crammed in there are being moved out. When we arrive, a small group of people is boarding a bus which has seen better days – several of them don't like us taking their picture as they pass by: some pull the curtains, others give us the finger. Some of them smile. They are supposedly being taken to Nové Zámky and Prešov.

Is politics involved?

But how are so many people crossing from Hungary to Slovakia? There already are theories about this, at least from the Slovak parties. Elections are due in Slovakia in just a few weeks, on 30 September, and illegal migration has become a hot topic in Slovak public life. According to the Híd/Most party, the reason why so many migrants have appeared in Slovakia is because the Hungarian police have been idle. The party's president has even claimed that Viktor Orbán is trying to influence the Slovak elections this way.

The Sme Rodina (We Are a Family) party also claims that the Hungarian authorities are aware of what is going on and has accused Hungary of "deliberately putting Slovakia and other EU countries at risk". "The Hungarian police aren't stopping the suspicious vans – they don't want any paperwork for themselves, while they know full well that the migrants are heading for Slovakia," the party's president wrote on Facebook, saying Slovak police believe the Hungarian authorities have been instructed not to detain refugees heading for Slovakia. Orbán's ally in Slovakia, Robert Fico, who leads the polls with his party Smer, is campaigning by demanding the closure of the Slovak-Hungarian border as soon as possible.

We also brought up these allegations with the mayors of Slovak villages hard hit by migration.

The mayor of Ipel'ské Predmostie can't imagine the police being ordered from higher levels not to apprehend the arrivals, "but I can imagine them just letting it happen. I can imagine that, yes". According to the Slovak authorities, there were 11,000 illegal entrants registered in Slovakia in the whole of last year while this year they are already at more than 24,000. The mayor concludes by saying that 'the math is clear for everyone': he claims that of the 24,000, about 20,000 have entered the country in the last two months, 'almost out of nowhere', with the vast majority of them crossing along the 150-kilometre stretch of the Ipel, placing an 'infinite burden' on the 50 or 60 Hungarian settlements and their mayors.

What the mayor of Vel'ká Čalomijca doesn't understand is why the large influx into the region suddenly started in the last few days, but he also says: "I think the Hungarian side is doing what they can. They can't stop it there, it's impossible to catch everyone there, the border between the two countries is 655 kilometres long. We are happy that Hungary has done its job. I have nothing against Viktor Orbán, I am neither for nor against him. But we are grateful for his policies, while everyone is attacking him and Brussels hasn't supported him in stopping the flow of migrants." In his opinion it's a "conspiracy" that it has to do with the Slovak elections, although he admits that "the timing is interesting, but I wouldn't dare say it's by design".

The mayor of Koláre has similar views, and says that Hungary has already done enough by putting up the fence on the Serbian border, and "I'm sure you have other problems that are more important than these. Although it's true that this is also quite important".

The mayor of Lesenice doesn't want to get into politics, as the elections are coming up, but says, "what can I say, where would the Hungarians put them? Well, I'm not saying they're doing everything possible, but they're being clever about it, I think. Who wouldn't? Sometimes the bottom of the car is almost touching the ground, and we watch the police just stand there without stopping them. But from what I've heard, most of them are caught down there, on the Serbian border". But more and more people have been crossing the Hungarian-Serbian border in recent months as well, with cars and vans left on the side of the road being the most visible sign of the migration situation there.

The police is in dismal state

We spoke with a source who has insight into the situation on the Slovak-Hungarian border and into Hungarian police circles. They say the situation is "depressing" because there are not enough police and therefore it’s not possible to catch everyone. According to them, even senior officers are being transferred to patrol duty, while the border guards do not have the proper technology they used to have.

They say the current situation isn't even a shadow of what it used to be, and what would be needed now is an organisation like the border patrol to stop illegal migration. "We used to have border patrol detectives – the moment a stranger appeared, the phone would ring. There used to be barracks in every third village along the border, which were completely self-sufficient. They kept pigs, rabbits, chickens, it was a well-organised system. They had thermal imaging cameras, all-terrain vehicles. With the police taking over, this became a thing of the past".

After Hungary (and Slovakia) joined the Schengen zone, the classic system of border patrols was abolished in 2008, and the almost 10,000 border guards were integrated into the police force. According to our source, the cars have been scrapped, and they themselves still come across advertisements selling the green SUVs of the former border police.

Our interviewee also says that to their knowledge, the authorities apprehend only 2-3 percent of illegal border crossers, with the majority getting across the border easily. Sometimes the van only takes them as far as the border, where they are dropped off and told to walk, but there are some who cross easily even on public roads in minivans with Hungarian license plates. "Hundreds of cars drive between Hungary and Slovakia every day, but there is no systematic control, which would at least stop the minivans. Then there are the places where only a boundary stone marks the border with the other country, but it’s located in a ditch. No fence, no nothing, one may simply pee across into Slovakia".

Meanwhile, "they are building the new bridge at Drégelypalánk and Őrhalom and there is not a soul there. No policeman, no border guard, nobody. They can come and go as they please," our contact says, and when we visit these places, we can see that they are right. We can drive onto both bridges under construction without any problems or resistance, and the only ones we see there are the workers. The only problem is that neither of the bridges is finished on the Slovakian side yet, so driving across is not possible, but one can cross on foot without any difficulty.

Contrary to what some Slovak parties claim, according to our source, the enforcers at the bottom of the hierarchy (which is where the patrols belong) have not been ordered to either release or not apprehend those crossing the border, but there’s a possibility they are 'being bled dry from above so they'll be weak'. Who knows".

The Slovak police chief also admitted that the numbers of their police is not sufficient to stop the current mass migration at the border. For this reason, the country's expert government decided a few days ago to deploy 500 troops to the Slovak-Hungarian border to relieve the police, but they don't intend to introduce border controls. We cannot be behind every tree, but there will certainly be a bigger police and military presence. There may be checks at some crossings, but not everywhere. However, if, for example, a closed van arrives, it may be checked", Lajos Ódor, the Slovak Prime Minister of Hungarian descent said.

The PM did not wish to "speculate" on what was causing the sudden surge in numbers. "Refugees are not coming from Mars, they are arriving via Hungary, but they are also trying to enter Austria from Hungary in the same or perhaps even greater numbers," he said. According to Ódor, the strengthening of the Slovakian route may also be due to the fact that the Austrians have recently tightened border controls at their border with Hungary.

He also did not want to theorise about whether the number of refugees arriving in Slovakia may be affected by the Hungarian government's release of convicted foreign traffickers who were expelled from Hungary but it's not checked whether they actually leave the country.

We sent questions to the Hungarian Ministry of Interior about the situation at the Hungarian-Slovak border and asked about the number of police officers working there. We also asked what they thought about the allegations made by some parties in Slovakia that this is how the Hungarian government is trying to interfere in Slovak domestic politics in the run-up to the elections, or that they think the Hungarian authorities have been ordered to allow migrants to cross into Slovakia without being checked. We didn’t receive any answers before publishing our article.