They knew they were memorializing themselves, that they were the last Hungarian Jewish community in Mukachevo

For three years in the 1990s, photographer Éva Horvát documented the life of the last Hasidic diaspora in Mukachevo, (Ukraine) which has since died out. The community, which identified itself as Hungarian had suffered many traumas, yet there were still those who, in spite of the town's troubled history, after surviving the Holocaust and the Gulag, returned to Mukachevo to continue to follow their religion and go on despite their constant struggle with poverty. The Jewish community in Mukachevo had flourished from the 19th century onward, and its numbers declined steadily in the 20th century, especially after the 2nd World War and the break-up of the Soviet Union. The community eventually disappeared altogether. Éva Horvát pays tribute to the meeting of tradition and everyday life and how religion, the force that binds a community together, can help rise above so much trauma and hardship.

"This project started somewhat by chance, like almost everything else in life," Éva Horvát, who came into contact with the community through Miklós Rékai, an ethnographer of the Jews of Mukachevo, says. Rékai had been researching the lives of the remaining Hungarian-identity Jews in Mukachevo for a year when Éva Horvát was offered the opportunity to join the project.

"It was a really big opportunity. I was very interested in this community, whose identity was defined by their origins and traditions, while they were living in socially different living conditions. Their system of traditions was rooted in an identity from a very long time ago, while on the other hand, their lives were defined by the pre-war period, the Holocaust, communism, and the regime change as well," the photographer explains.

She spent three years documenting the life of the Jewish community in Mukachevo, including visiting their religious festivals. "We would spend three or four days with them each time, staying in their homes, living with them," she says.

Horvát regularly visited the last Jewish diaspora in Mukachevo between 1992 and 1995, and the Hungarian Museum of Ethnography held an exhibition of her pictures in 1995. Later, the pictures appeared in various collections in several countries, although not in Mukachevo: the people of Mukachevo came to Hungary to see them.

The photos are now being published as a book for the first time under the title "Fallen Oaks, Scattered Seeds" – we chose a selection of the text and pictures from the publication and spoke with Horvát about how she and Rékai experienced the three-year project. Éva Horvát's photographic material is a memorial to the last Hasidic community in Mukachevo, and provides us with a glimpse into the poverty of socialism and the collapse of Transcarpathia after the fall of communism. At the same time, the photos also give insight into the life of a community traumatized by war, whose members, in their own way, are holding on to what keeps them together – their traditions and their religion.

For a long time, Mukachevo was one of the centers of Hungarian-speaking Jewry, the bastion of Hasidism in Hungary, as the book describes it. It was in the 17th century that some Jews from Galicia and Ukraine came to the area of Mukachevo and founded a new community. They were trying to escape the rule of the Zaporizhzhya Cossack Bohdan Khmelnitsky and the ethnic cleansing that took place under him. The Jewish congregation was officially established in 1741, and the town was given a synagogue.

The community soon began to flourish: as the book describes, the number of Jews in Transcarpathia almost doubled between 1869 and 1910, from 64 903 to 128 791. "In 1778 there were already Jewish craftsmen in the area of Mukachevo. [...] The Jews are taking an interest in the public affairs of the city, and they also take a keen interest in the election of judges. In 1792, the Jews consumed wine at the rate of 9 pints", Imre Csetényi wrote in his 1928 text on the Jews of Mukachevo, in his work describing the presence of Jews in the area in the 18th century.

In 1941, the Hungarian army marched into Mukachevo, and the persecution and harassment of Jews began. As Horvát says, before the war, at least 50 percent of Mukachevo's population was Jewish, and the Holocaust became a huge watershed.

"When the Hungarians marched into Mukachevo in 1941, the Jews rushed to greet them, since they too had a Hungarian identity, and they worshiped the Hungarians…Even in the 1990s they considered themselves Hungarian, but they could have been Russian, Ukrainian or Czech too, as they had lived under so many different regimes. But they were Hungarian Jews. And it was the Hungarians who took them away in '41," the photographer says. Ferenc Jávori, a native of Mukachevo of Jewish origin and the author of the foreword to the book, says that "after the war there was still Jewish life in Mukachevo, but later everyone who could, emigrated". While from the 19th century onwards the Jews of Mukachevo were practically inescapable in Jewish correspondence in Central and Eastern Europe and in the Jewish religious world, after the fall of communism this diaspora disappeared completely.

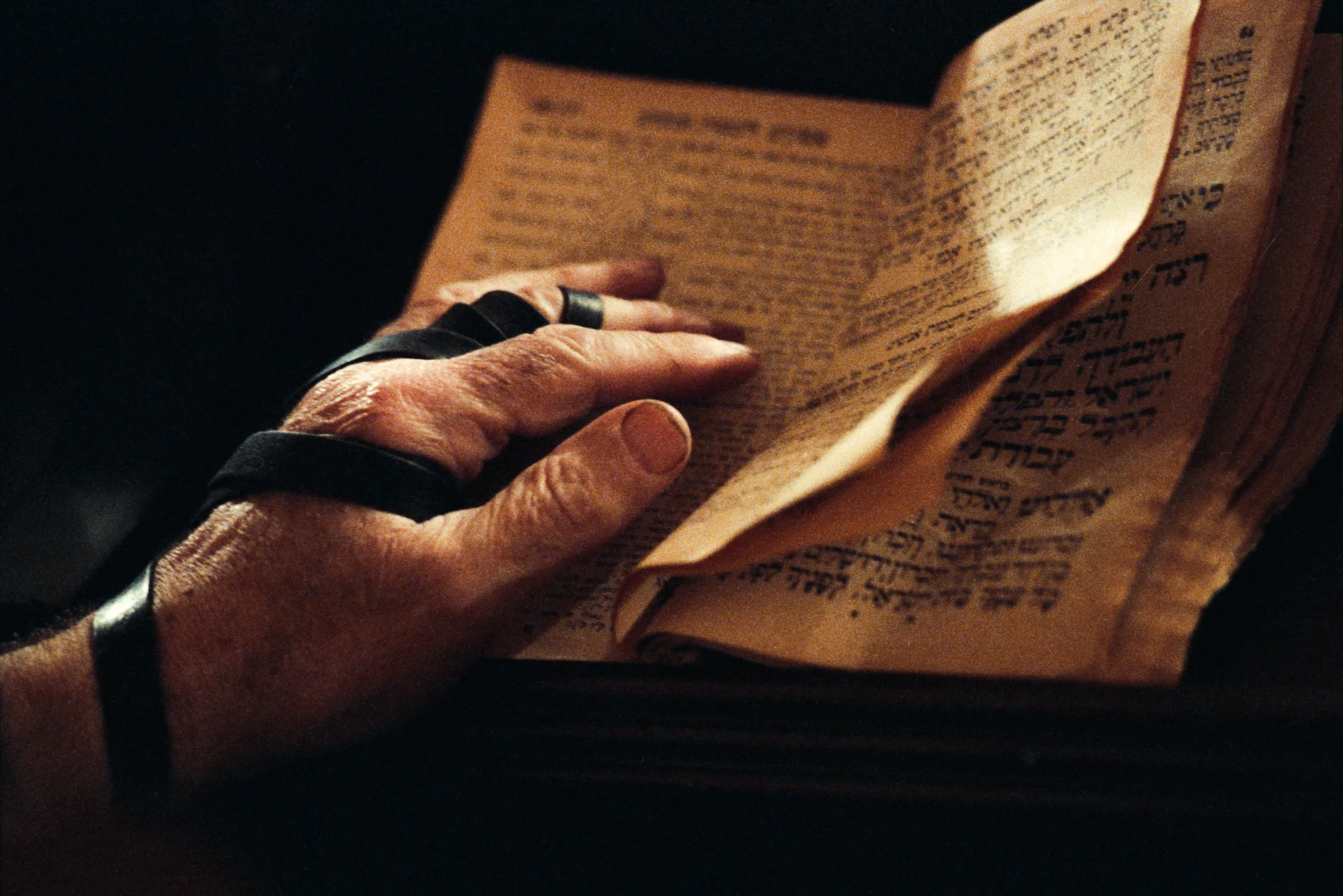

After the war, under communism, synagogues were given new functions. In Mukachevo, before the war, there were synagogues and places of worship, but after the Second World War there was no synagogue left, so the community of Mukachevo established a so-called "stiebel" (synagogue in a home). According to the book, the three windows to the right of the entrance opened into the men's room, while the women's room looked out onto the courtyard. Of course, there were exceptions, some prayed alone: the main character in the picture above, for example, was the last religious Jew in his family. As the book says, 'his son, with whom he lives, married a non-Jewish woman, and he, in order not to be a bother, or perhaps so that they would not disturb each other, prefers to retire to pray in the dim light of the room used as a pantry and a workshop'.

"When I first entered the stiebel, I entered the women's room, where they looked at me and said: Look, here is a young Jewish woman. And that was that," Éva Horvát recalls her first encounter with the community in Mukachevo:

"It was important that I myself am Jewish, although I come from an intellectual family in Pest. We had a lot of traditions, but it was in Mukachevo that I really discovered where the traditions in our lives came from."

Following the collapse of the Soviet market in the years after Ukraine's independence in 1991 – when the pictures were taken – Ukraine faced staggering poverty. "There was not a single shop open, not a single petrol station in Mukachevo during those three years. If you didn’t see too many goods for sale when you went to the market, it wasn't because they had run out of supplies, but quite simply, that was all there was. In Hungary you couldn't really see the collapse of socialism, but there you could," Horvát recalls. She adds: the poverty was terrible, but people protected themselves by trying to keep their spirits up even in the midst of this great poverty."

She recalls that during this period, urban life essentially disappeared, as there was no water supply, and this kind of poverty was also felt inside the apartments. “For exampl, we saw a woman who, instead of retiring chose to go to work in a factory so she could get a pint of milk to give to her grandchild. People didn't go shopping. Instead, they would go out to find something: groceries, or a sweater. Someone from each family had to sit by the tap to be there when the city turned on the water twice a day. There's a picture of Bumi cleaning the rooster in the bathroom – he did it there because there was no water in the kitchen.”

The rooster is one of the main motifs of the Kapparot, the day preceding the Day of Atonement. On this day, as the book describes, "the Eternal's mercy is most felt on the morning of the Day of Atonement and the preceding day, so the men take a rooster and the women a hen, say a prayer, and then spin the animal three times over their heads while repeating the Hebrew phrase "this is my exchange, this is my substitute..." three times". It is believed that the animal can redeem people from their sins.

Following the ritual, the animal was slaughtered according to tradition, and its meat was either donated to the poor or eaten as soup. The Jews of Mukachevo, like the city's population, were poor, so they cooked soup. If one did not have money for a rooster, or if there was no rooster on the market, one could replace it with fish: in Mukachevo, it was common to make a Kapparot with fish, which, as shown above, was done by women on the doorstep. Horváth says that there is no previous record of the fish being placed on the doorstep as part of the ceremony, this was a unique tradition of the Jews of Mukachevo.

“Some survived Auschwitz and lived through the Gulag, but still went back to Mukachevo. Later, these same people had to flee from the unlivable poverty of post-communism. The ones we see in the photos are the ones who chose to stay even under such circumstances. The community that survived in spite of all that history was mostly made up of Jews with a Hungarian identity. They had no rabbi, and could only follow their religion in secret during the years of communism” – Éva Horvát explains.

According to Jewish tradition, on the eve of Shabbat, on Friday, the woman of the house lights the Shabbat candles, and the holy day begins. After The Holocaust, some of the women among the returned members of the Jewish community no longer lit a candle on Shabbat. The spirit of anti-religious communism further reduced the number of candle-lighters in Mukachevo. The book tells the story of Hindu “whose loved ones, who were murdered in Auschwitz appeared in a dream and asked her how she could have given up on this ancient tradition. Hindu counted a total of thirteen living and dead relatives in her dream, and decided to start lighting the candles again. Beginning on the very next Friday evening, she lit thirteen candles, but – for fear of it being illegal to practice her religion – instead of the living room, she lit them in the windowless bathroom. She only dared move the candle holders to the living room after the regime change.”

Even after the fall of communism, members of the Jewish community of Mukachevo continued closing the living room curtains when lighting the candles. Horvát explains that “when it came to practicing their religion, theirs was a closed community. They didn’t want others to see this. Naturally, people knew they were Jews, and this was no problem. The Christians took cookies to the Jews, and the Jews gave cookies to the Christians. Once, we asked the Mukachevo Jews whether they celebrated Christmas. They said that they did. And who brings the gifts? – we asked. The Jewish angel, of course! – they replied. They had an answer to everything.”

“I was less interested in the religious part – that was a crutch. On one hand, I was interested in the tradition, and on the other hand, in how they lived, what their homes were like. It often happened that religion and everyday life blurred together.” – Horvát says. She explains that after the majority of the Mukachevo Jews who survived The Holocaust had left (mostly to the United States and Israel), those who remained became a completely unique diaspora: for example, they completely gave up on the external traditions of Hasidism.

“They stayed in Mukachevo, because it was their home. One always goes home to something. Maybe because they expect someone who had disappeared to come looking for them there. Or because leaving doesn’t even occur to them. Those who were better-off could leave sooner, the poor ones were those who stayed – Horvát says. They had already experienced their own reform, but they couldn’t be called reformed Jews. Giving up on external things or adjusting to trying to stay alive was not something they saw as reform.”

One of the above photos portraying men are of the Tashlikh, an old Jewish custom when the community walks to the waterfront following afternoon prayers on the first day of the new year. In Mukachevo, they went to the Latorica river: here they said a special prayer and shook the edges of their clothes – symbolically casting off their sins. In the photo below, Hindu is preparing "mishloach manot” or handmade food gifts.

"They kept their religion mainly according to their memories, there was no rabbi. A rabbi only came when it was evident that this diaspora was going to disappear," Éva Horvát says. According to Orthodoxy, a diaspora cannot cease to exist, which is why Rabbi Hoffmann Chayim Shlomo came to Mukachevo in the early 1990s.

“The fact that this diaspora, which represented the whole of Central Europe at one point or another, eventually died out is a sad story. But it is interesting that they knew that their story was important. They welcomed us, and I was able to photograph them precisely due to this moment of grace which existed because the people of this community were aware – as much as I was – that they were going to memorialize the Jewish community of Mukachevo."

"At the time, Mukachevo was completely different from Budapest. The majority of the Jews in Pest had already assimilated before the war, while in Mukachevo there was no need to assimilate, there was no one to assimilate to", Horvát explains. As she says, in Mukachevo, you could find everyone from the wealthiest to the poorest, living in completely different economic situations, but by '92 it was mainly the poor who were still there. “Compared to Pest, being Jewish didn't just mean being middle-class there. But the poor also read, studied, and practised their religion in the same way.”

When we asked Éva Horvát what it was that stuck with her the most from those three years, she said, "the creativity with which they lived. The way they were able to reconcile their religious identity with everyday life." In the picture above, for example, the man is standing at the door of the stiebel, both inside and outside. He did this because on holidays it is not allowed to use electricity, including the telephone: he didn't want to break this rule, and wanted to be on the safe side. But Horvát also told us about the time when they asked the community what they should bring for them from Budapest, because they always brought them something: "They told us to bring salami. When we asked them, 'What makes it kosher? "Well, the fact that I'm the one eating it," was the response. What they were doing was very realistic, they were not dogmatic about religion."

"To me, this book means that we have really erected a memorial to this community. It also means that when you take a picture, you may not know everything about the picture yourself. The people I show the pictures to, whether they are traditionalist Jews, researchers or rabbis, they always see meaning in the pictures. The significance of this book is also that these signs will be researchable."

– Horvát says, adding that her dream is to continue the project should the book be successful, to see what happened to the community. “I'd look for their descendants, go to Brooklyn, to Mukachevo, to Israel. Few people are in Mukachevo by now. It's interesting that a synagogue has been established since the community ceased to exist. That's where the descendants go back from time to time.”

During the holiday season, Horvát was also able to witness special events such as weddings. This photo, for example, shows the tradition of covering the bride's face (bedeken), just as the Jewish foremother Rebecca covered her face with a shawl when she saw her fiancé Isaac. But it also symbolizes that the groom loves the bride not for her appearance but for her inner qualities. According to Jewish tradition, after the wedding, the couple's happiness at being married is immense, so the celebration lasts for seven days.

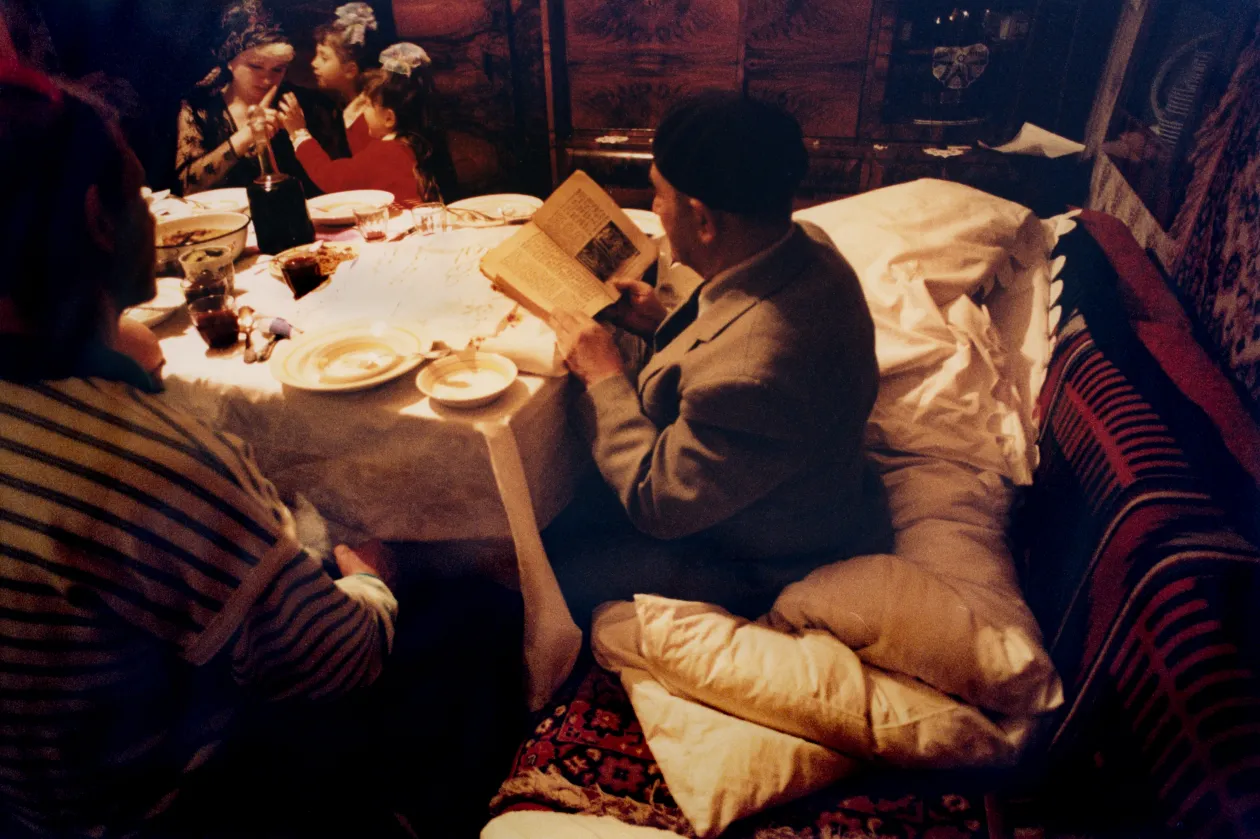

Pesach, the feast of unleavened bread, shown in the pictures above, carries similar beauty. For Jews, Pesach is an annual reminder of their liberation from slavery in Egypt, and on Seder night the older generations pass on the story of the Exodus to the next generations. To make it even more exciting for the children, at the beginning of the evening, the host hides part of a matzo-bread for the children to find. Pesach is governed by strict rules. Just as baking the Pesach bread from two simple ingredients is a serious matter, so too are the preparations: even in the poorest religious Jewish household, during this holiday they use a separate set of utensils, ones that have not come in contact with leaven.

There were only a few people left in the community who had lived through both The Holocaust and the Gulag. Éva Horváth says that while they told stories about their traumas, they did not live in the tragedy. Instead, they tried to remember the good things, like their childhood. "They were not taken away in '44, like the Jews of Pest, but as early as '41. They did not lament though, they just recounted how it had happened. They didn't give details, they preferred to remember their childhood, their school experiences, they preferred to live in the good stories," the photographer says.

Horvát then adds: “They told me about life before the war, about the scarcity of food and how they always looked forward to Saturday, not only because it was a holiday, but also because there would be cholent – so they could finally eat well. In regard to The Holocaust, they found it especially painful that it was the Hungarians who took them away – since they felt Hungarian themselves. They spoke eight languages, but in the synagogue they spoke Hungarian, in the community they spoke Hungarian. But one thing they didn't talk about was The Holocaust – not because not talking about it was like not remembering it. They didn't talk about it because not talking about it was as if they didn't have to suffer all that humiliation. It's as if they didn't have to live through all that inhumanity.”

Fallen oaks, scattered seeds – The book by Éva Horvát and Viktor Cseh will be published on 9 June 2023.