It is easy to give an answer to the question of whether 'szaloncukor', the characteristic Hungarian Christmas bonbon is a Hungaricum: technically no, because it is not included in the official list of Hungaricums in the Hungarian Heritage Repository. (The discussion on what the point of having a list of Hungaricums is and whether it even makes sense at all shall be figuratively wrapped in tissue paper and coloured foil and will not be opened up in this article.)

However, if the question of whether these Christmas bonbons are a Hungarian invention is brought up, we can find a viewpoint from which the answer is yes. As an ornament on a Christmas tree to be consumed (sometimes secretly at the expense of family members), Christmas bonbons are almost certainly a Hungarian custom. Still, all the elements of this custom can be found in other nations, too, from much earlier times.

Candy cooked from sugar

Let's start with the candy itself! The ancestor of the Hungarian Christmas bonbons is fondant and is French in origin, where it was already known in the 14th century. In fact, fondant is a more attractive form of plain sugar: it's a sugar paste that has been oversaturated by cooking and then cooled. At this point, it is necessary to recall a statement from primary school science lessons that is difficult to remember: a solution is oversaturated if, at a given temperature, it contains more solute than the solvent can dissolve. In this case, the solvent is water and the solute is sugar. The water is boiled, a lot of sugar is poured in, and the sugar dissolves at a high temperature. The solution is then cooled until the sugar in it begins to crystallise, but the cooling liquid is continuously stirred during the process to prevent the crystals from forming bigger pieces. The end result is a thick sugar paste with a pleasant (microcrystalline) texture, which of course still has a net taste of sugar, but can be packaged as a sweet after the addition of flavouring and once it has hardened.

Exactly how and when fondant became Christmas bonbon is not known, but the French also have a nice legend about the custom of packaging candy by the piece. According to this legend, sometime in the late 18th century, after the French Revolution, there lived in Lyon a master confectioner called Papillot, whose valet got entangled in a love affair with a woman much like cocoa butter gets entangled with chocolate coating. The woman lived above or opposite the confectioner (and according to some sources was a relative of Papillot), so the valet saw her often. He had a peculiar way of courting: he would write love notes on pieces of paper, wrap a sweet in it, and bombard his sweetheart with the wrapped treat. How successful this manoeuvre was is not known, but Mr Papillot noticed that someone was pilfering sweets and caught the valet in the act. Then, however, he took a liking to the idea and started selling individually wrapped treats, the inside of the paper always containing some kind of wisdom or joke. The papillote, reminiscent of Christmas bonbons but typically more chocolate-based, became a popular sweet that is still popular in France today.

Whether wrapped or unwrapped, the most popular theory is that fondant probably arrived in Hungary through Germany in the early 19th century. Several Hungarian articles mention the name of French master confectioner Pierre André Manion, who took the know-how to the Germans, but this is highly doubtful, as refutations of the claim can also be found, and it is also suspicious that Google throws up zero hits for this name on French-language sites. Another theory is that Turkish confectioners also cooked fondant-like sweets and that this may have influenced the first Hungarian fondant sweets (which were also called soft candy).

The Christmas tree also arrived in Hungary in the 19th century, sometime in the 1820s. According to the memoirs of Baron Frigyes Podmaniczky, one of his aunts put up the first Christmas tree in 1825, other sources say that it was Teréz Brunszvik who did it in 1828, and the third wife of Emperor Joseph the Great, Maria Dorottya, was also among the first to do so. The trees were decorated with paper ornaments, fruit, nuts, cookies and other snacks, as was the German custom.

Up to the tree!

Thus, the fondant and the bow-like wrapping are French, and the Christmas tree and the idea of hanging food on it came from the Germans, but it was probably the Hungarians who put it all together in a formula. So if it makes you feel any better, you can call the Christmas bonbons hung on the Christmas tree an unofficial Hungaricum.

And another Parisian influence: in the Hungarian Reform Era (from the 1820s to the 1840s), the parlour or living room of Hungarian bourgeois homes was called a salon, according to the French manner. In this room, there was often a bowl of sweets, even wrapped fondant, for guests to snack on. And since the Christmas tree was typically located in this room, the candy in the parlour found its way and joined the rest of the stuff hanging on the tree. Exactly when this happened we don't know, but it must have happened sometime around the time of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. As early as 1870, renowned novelist Mór Jókai wrote that his family had a “salonzuckerl” hung on the Christmas tree – a word he had no difficulty in coining, because salonzuckerl already existed in German, though not on the tree.

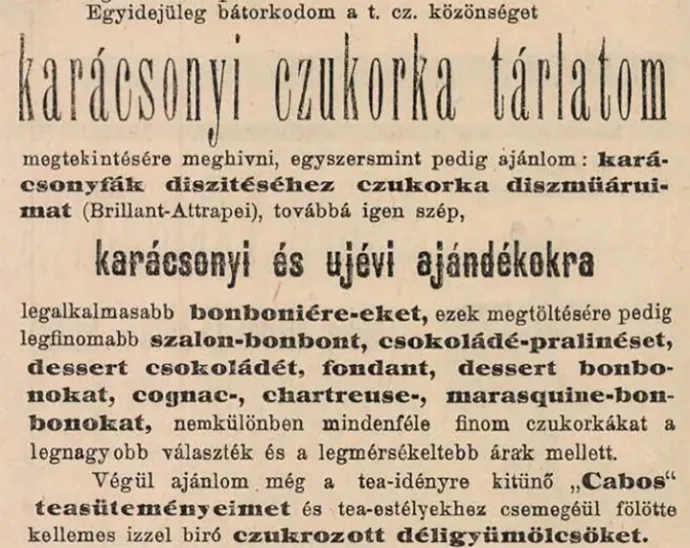

At the end of the 19th century, Christmas bonbons spread like wildfire in Hungarian bourgeois homes. At first, it was fondant sugar without chocolate coating, and it was made by hand. Then a German entrepreneur Frigyes Stühmer opened a steam-powered chocolate factory in Pest in 1883, and a few years later the first Hungarian fondant-making machines were started up here. One of Stühmer's clients, Emil Gerbeaud, also opened his own chocolate factory in 1886, where fondant production was introduced as well.

Christmas bonbons quickly became diverse sweets, with each famous confectioner having their own recipe, and customers could even order a combination of different flavoured sweets in a box. Poorer citizens cooked their own Christmas bonbons at home, and they had more and more ideas to choose from.

After the two world wars, the mass production of Christmas bonbons resumed in the 1950s, but there were far fewer varieties than at the end of the 19th century. It was then that chocolate-dipped Christmas bonbons really began to take off, although the uncoated version continued to be popular for a long time. From the 1970s onwards, jelly Christmas bonbons became the biggest hit. (The jelly-like texture is due to gelatine, which is the raw material for all animal connective tissue, so the bonbons' jelly-like texture is the same thing that makes aspic so nicely transparent – although in recent years vegan-friendly vegetable gelling agents such as pectin or agar-agar have become more common.)

The huge selection from 130 years ago is now back for the holidays. There are over 150 varieties of mass-produced Christmas bonbons, but this is only the tip of the sugary iceberg because the number of artisan bonbons made in confectioneries can be several times higher. Hungarians spend billions of forints on Christmas bonbons during the festive season, and according to an article by Inforadio in 2018, this amount was just under 6 billion in that year, with an average of 1 kilo of bonbons per household.

In the early 2010s, more attention was paid to the trans fatty acid content of Christmas bonbons after it was found to be too high in most products. In principle, this should not be a problem since 2014, when regulation came into force that capped the amount of trans fatty acid (up to 2 grams per 100 grams of food).

And for our readers who are brave enough to try to make a batch of homemade “szaloncukor”, we recommend the recipe linked here.

If you found this article useful, and would like to receive quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!