American murderer who blamed role-playing game for his actions released from prison after 38 years – Telex finds out

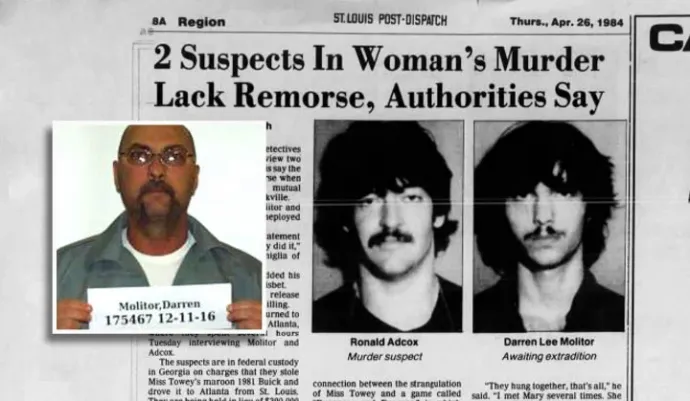

For our crime podcast about a case in Hungary, Telex wanted to interview an American murderer sentenced to life imprisonment, but it turned out that he had been released on parole. When he was a 17-year-old teenager, Darren Lee Molitor killed a young girl, and then added to the voices of moral panic around role-playing games, claiming that Dungeons and Dragons had corrupted his mind.

Darren Lee Molitor, the American sentenced to life imprisonment for murder, who became notorious in the US in the 1980s for blaming the game Dungeons and Dragons for his crime, is not behind bars for the rest of his life and has been released on parole, according to a Missouri prison source. He was released two months ago, on 16 September, Telex was informed.

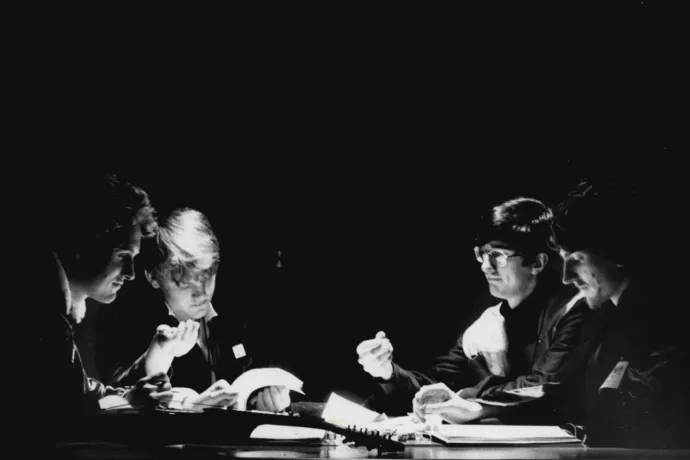

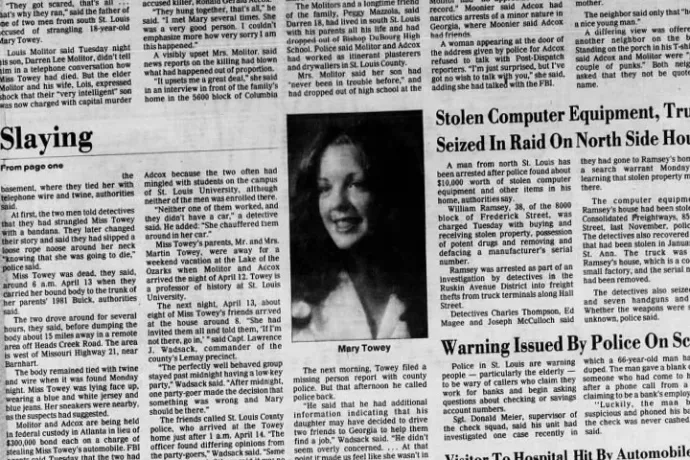

Born in 1966, Molitor caused the death of a girl about his age when he was 17 in April 1984. A group of young people in Missouri were preparing for Friday the 13th. They gathered, drank, and smoked marijuana. Some went to the home of one of the group, 18-year-old Mary Towey. They wanted to prepare for the party Towey was planning to throw on Friday the 13th.

It so happened that Darren Lee Molitor and a boy named Ronald G. Adcox stayed in the house all night, listening to music, drinking, smoking marijuana, and practicing martial arts. Mary went to bed around 2 a.m., but woke up early the next day, took a shower, and soon joined the boys, who taught her martial arts moves and then chased her around the house. The girl ran down to the cellar, where they caught up with her, overpowered her and tied her hands and feet.

"Messing with her mind"

Molitor kept repeating afterwards that they were just “messing with her mind". Mary was left tied up in the cellar for a long time, as the boys went upstairs and continued drinking, while she kept shouting from downstairs for them to untie her. At one point, Molitor went down and tied an ace bandage around her neck. Although he later claimed to have checked and found it loose enough, the tape proved fatal. While Molitor was back upstairs drinking beer, smoking pot and listening to music with his partner, Mary died downstairs.

The next time Molitor checked on her, he found her dead. Her death was caused by the lack of oxygen to her brain due to the tight tape. Molitor and the other young man, Adcox, panicked, gathered some valuables from the apartment, put the body in the trunk of the girl's own car and drove away from the house. They buried Mary in a wooded area.

However, the body was found, the FBI began searching for the boys, and they, Molitor and Adcox, turned themselves in to the detectives. Molitor eventually confessed to what he had done, but denied responsibility.

Instead of putting himself in the spotlight, he put the focus on a game called Dungeons and Dragons.

Originally launched in 1974 and played by millions, the game was at the time being declared something of a bogeyman after some high-profile incidents, thanks to a number of opinion leaders who were in the limelight a lot. Concerns about the alleged effects of role-playing games escalated into a moral panic in 1980s America.

Public consensus traces the beginning of the panic to the disappearance of a 16-year-old boy named James Dallas Egbert in 1979. Egbert was a young man of rare talent but with severe mental problems. As it turned out later, it was wrongly suspected that his disappearance was linked to the role-playing games he liked and the tunnel system beneath the Michigan University campus. Egbert was found safe and sound about a month after his disappearance and, as it later became clear, he had not been wandering in the tunnels at all.

The fact that he turned up did not mean that his life was sorted out. In 1980 he eventually committed suicide. Somehow, the tunnel fantasy captured the imagination of so many that, instead of the young man's real tragedy, this fictional story became fixed in people's memories and seeped into pop culture, most notably through the 1982 film Mazes and Monsters, in which Tom Hanks had one of his first roles.

Demons, witches, occultism, violence, murder – these are the things critics have accused Dungeons and Dragons of introducing to unsuspecting young people. Aside from the Egbert case, the main fuel for the moral panic was the suicide of a Virginia high school student named Irving Lee Pulling in 1982.

The boy's mother, Patricia A. Pulling, blamed the tragedy on role-playing. She founded Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons (BADD) and spoke out against the game at every opportunity, claiming it had corrupted her son.

Satan's tool

Darren Lee Molitor's case was unique in that he was not framed from the outside, but claimed himself that his thinking and personality had been distorted by Dungeons and Dragons. He wanted to have two so-called experts on the subject heard in his court case.

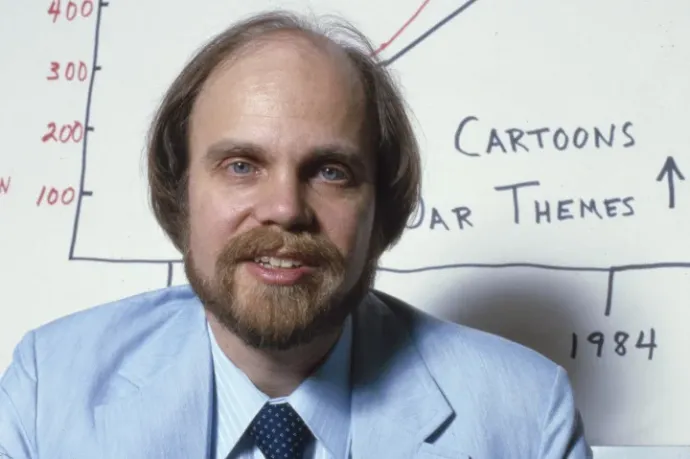

One was to be Patricia Pulling herself, and the other was to be a psychiatric doctor, Dr Thomas Radecki, who was later convicted of criminal offences and banned from practising. If given the opportunity to appear, Pulling would have discussed the violence in the game, and Radecki would have testified that, in his opinion, role-playing desensitises players, preventing them from assessing the danger of their violent actions.

However, the court, in agreement with the prosecution, concluded that these two so-called expert witnesses would be irrelevant to the murder case. Molitor even tried to appeal the case, but the Court of Appeal also found that the original decision was correct, if only because Radecki, although a doctor, had no specific knowledge of the accused. He had never examined him or spoken to him, nor had Patricia Pulling.

Darren Molitor claimed before his sentence was pronounced that his trial was not fair, without the expert hearings he had requested. In 1985 he wrote an essay on the subject. In it, drawing on more than three years of experience with the game, he wrote that he believed that for most players, Dungeons and Dragons became an escape from reality, a release from anxiety and tension, which was a good thing, but that it was very dangerous, especially for young people, to expose the mind to all the violence that was part of the game.

But the essay also has stronger elements: in it, Molitor outright calls the game a tool of Satan, and at the end warns everyone against playing it.

We looked for Molitor, but couldn't find him in the prison

For nearly four months, Telex has been preparing a crime podcast, which is expected to be published in the first half of next year. The topic is a Hungarian case nicknamed "the role-playing murder" in the media. In the podcast, we will also look in detail at role-playing games themselves and the prejudices surrounding them, mainly because of the nickname of the case and an argument that also appears in the judge's reasoning.

We thought it might be interesting to try to get Molitor, serving a life sentence, to tell us how he looked back on his life and the crime he had committed after almost 40 years – whether he still thought that role-playing had got him where he was.

We contacted the Missouri state correctional facility where Molitor was listed in the prisoner registry. The response from the facility revealed something that has not been widely publicized in the United States: Molitor has been released back into society under probation supervision. We have tried to contact him through his probation officer and will report back if we succeed.

The translation of this article was made possible by our cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.