“It took me a total of four hours to get there on two buses, and the same amount of time to get back every day. The work was tiring, I spent hours taking apart old electronics, but at least I got some money to help my family.”

– this is a quote from The Guardian which recently wrote about the experience of a 16-year-old Ukrainian girl who spent her summer as a refugee child working in a factory in Hungary.

According to the article, Alisa arrived in Hungary in April from Kharkiv, Ukraine's second largest city, which she and her family had left after weeks of Russian bombardment around their home. They first stayed in a hotel in Budapest and then were taken in by an elderly couple in the countryside. Their hosts had initially said they could stay as long as they needed accommodation, but they were eventually asked to leave because of the spiralling utility costs. The girl's parents are planning to return to Ukraine, but as they don't know if their home in Kharkiv is still habitable, they are initially just going to Lviv to stay with friends. Alisa will stay in Hungary for the time being to continue her studies at an art school.

Telex tried to contact the girl interviewed in the Guardian article, but we were unable to get in touch with her. A source who knows the girl confirmed the report of the British paper, but declined to give any further details. Thus, we have no information about which factory Alisa worked in, under which job title, under what conditions and whether she was working legally at all.

As refugee children are always exposed to increased risks, the case may raise concerns about exploitation and illegal child labour, while it should also be borne in mind that it is perfectly legal in Hungary to work from the age of 16, and summer student work in a factory is quite a common experience for many Hungarian teenagers.

In this article, we have sought to find out, with the help of experts, what can be known about the situation of Ukrainian refugee children in general and the dangers of child labour.

Families made homeless by the war

Children fleeing war are always at increased risk of exploitation as well as violence and abuse. UNICEF published a leaflet on this issue in Hungarian at the beginning of the Russian-Ukrainian war in the spring. Among other things, it was pointed out that concerning minors arriving in Hungary from Ukraine it is also true that

- being threatened does not end for them once they have left the specific conflict zone,

- they can easily become targets for human traffickers,

- and they are also at risk of forced labour.

The head of the Anti-Trafficking Programme of the Hungarian Baptist Aid told Telex that the risk factors for refugee children are vulnerability, lack of language and local knowledge, and the lack of social embeddedness, and of a safety net based on familiarity. Agnes De Coll also said it should be borne in mind that Ukraine was already an "emitting country" for trafficking and exploitation before the war, and

“those fleeing extreme poverty, those looking for a way out, including minors, had already often headed west in search of a better life, a vulnerability that unfortunately some already exploited.”

The outbreak of war then exacerbated what had not been a rosy situation. Families, women and children who were previously living in stable financial circumstances are now forced to leave their homes. Even those who had prospects while living in Ukraine have become vulnerable," explains De Coll.

“They are fleeing the war, and their lives are now made hopeless by the fact that they don't know how long this situation will last, while they have nowhere to go back to and are living as quasi-homeless. They are trying to get a foothold somewhere without knowing how long they will stay, so they cannot plan for the long term, and this significantly weakens their self-reliance.”

Children arriving alone and accompanied by an adult

According to Ágnes De Coll, the good news is that, unlike war refugees from more distant countries in previous years, refugee children from Ukraine normally are not coming to Hungary via the green border. This is important because if there is a supervised border crossing, it is easier to spot unaccompanied minors, so they are more likely to enter the Hungarian child protection system. There, professionals will find out whether they were travelling alone or got lost en route, assess whether there is a possibility of family reunification and then look after them for as long as needed.

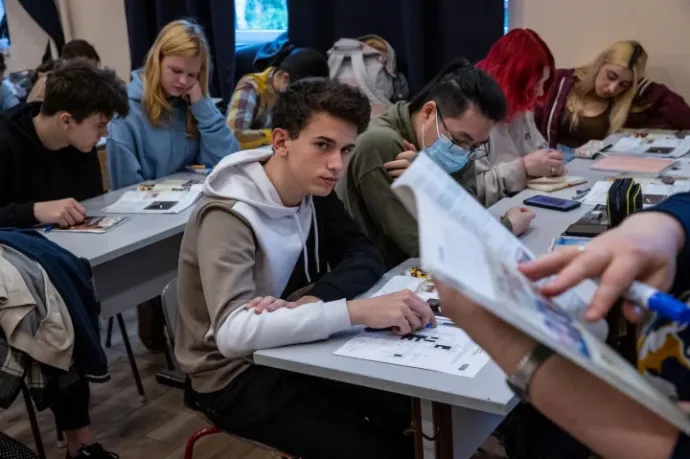

The programme manager of the Baptist Relief Service has also encountered situations where older children of secondary school age arrived in Hungary without an adult accompanying them, but their journey has been carefully planned. This was the case, for example, of the 15 teenagers whose parents contacted the Baptist Church in the hope that the children would be able to continue their studies in Hungary during the war. The result of this successful negotiation was that

these 15 high school students are now studying at the Kőrösi Csoma Sándor Bilingual Baptist High School in Budapest, and living in the temporary dormitory set up by the church.

The situation is different for children arriving with a family or accompanied by an adult. If they register as asylum seekers, they may be entitled to accommodation, care and regular cash assistance, but as the report of Átlátszó shows, many do not take advantage of this. This is partly because they do not know about it, and partly because work and accommodation arrangements are not coordinated. And the latter is of paramount importance, since the so-called "regular subsistence allowance" that refugees from Ukraine can receive from the Hungarian state is HUF 22 800 (56 euros) per month for adults and HUF 13 700 (33.9 euros) per month for children.

This means that if a refugee mother with three children does not have a job, and it is difficult to work a job if you have three children to look after, she has to make ends meet on 63 900 HUF (158 euros) a month.

Meanwhile, in January this year, experts estimated the per capita minimum cost of living for people living in their own homes at 130 thousand forints, (321 euros) and since then inflation has been breaking decade-old records in Hungary. Under these circumstances, it is not inconceivable that a teenager is willing to travel up to 8 hours a day to work in a factory and still be happy to support their family with money, as Alisa did according to The Guardian's report. This is especially the case when a 16-year-old girl is in a country where it is not otherwise considered blatant or automatically illegal for a young person of her age to work for the whole summer.

Illegal child labour does exist in Hungary

Although child labour is banned in Hungary, like in most countries that have ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, all our readers have probably encountered the institution of student labour and chances are that someone they know has taken a job legally at the age of 15 or 16. This is because, according to the UN, not all work done by minors is child labour. Only what can be defined as economic exploitation that endangers the child's education, health, physical, mental, spiritual, or moral development is characterised as such.

In Hungary, under current legislation, the minimum age for employment is 16, and according to the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights, the same applies to refugees from Ukraine (if they have asylum status or Hungarian citizenship). Anyone younger than this can only work for money in special cases, for example if they are a sportsperson, actor or involved in other artistic/cultural activity, or if they are over 15 and on a school holiday.

However, the operations director of the Children's Rights Foundation “Hintalovon”, Nóra Bárdossy-Sánta, also highlights the fact that the under-18s

- can only work with parental (legal guardian) consent, i.e. for a legal employment agreement to be established, in addition to the child, the parent must also sign the contract,

- they can work up to eight hours a day, but cannot be assigned to the night shift,

- they cannot work overtime,

- and they may not be assigned to work that could have adverse consequences for their physical stature and development.

Unfortunately, legislation protecting minors from exploitation is not always enforced. According to Ágnes De Coll, it is clear that the risk of exploitation also exists for children fleeing from Ukraine, especially in the agriculture, construction and catering sectors, but the Hungarian Baptist Aid' programme manager is not aware of any such cases. The expert adds that

“unfortunately, one does not have to flee war or even come from abroad to be a victim of child labour in Hungary.”

As an example, De Coll cites the case from the Hungarian village of Ócsa, reported by the police in August this year, where two adult men were forcing teenagers to work on construction sites six days a week, 10-12 hours a day. Although the children were housed in a shed, most of them did not feel exploited as they were paid for their work and lived in more comfortable conditions than the homes they had left behind. The Hungarian Baptist Aid programme manager said the story from Ócsa also shows that it is not enough to protect refugee children and children from extreme poverty with legislation, because

"if a child comes from a situation of complete hopelessness, it may seem like a good thing for him or her to have somewhere to earn money and even have shelter, no matter how bad the circumstances."

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!

The translation of this article was made possible by our cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.