It so happened that in 1956, my maternal grandfather became president of the Workers’ Council at the Szeged Fur Company. According to family tradition, he was liked by his coworkers and was elected by popular vote, which ended up determining my grandpa’s fate, who was in his fifties at the time. Having been charged with counter-revolutionary behaviour, he was sent to the Interior Ministry’s internment camp (transformed from the former Hussar barracks) in Tököl. After his release he couldn’t get a job at home in Szeged, so he went to Budapest where he worked as an unskilled labourer.

I also made it to the Tököl prison – as a journalist, at the turn of the millennium. At the time, my grandfather had been dead for twenty years, and the prison had been functioning as a juvenile detention facility since 1963. Although I was there to interview teenage inmates, I spent much of my time there thinking about where my grandpa may have sat and I stared mesmerized at the walls and anything else my grandpa might have seen, touched, sensed: the doors, the handles, the benches, the tall trees.

I was reminded of this search when I saw Dániel Kovalovszky’s photo series entitled: “The set for a play from hell” (Egy pokoli színjáték díszletei). Ah, yes, the set!

Looking at historical sets is one of the most exciting things in the world, and one need not go far to do it around here, it’s enough to go out to the street. A good example is Kossuth square in Budapest, where on 25 October 1956, people sought safety from the volley under the arcades of the building of the Ministry of Agriculture. The building is still there today and it still has the same function as it had under each Hungarian government since 1889.

Or another good example – and we have already arrived at Dániel Kovalovszky’s photos – is the well-known view of the hill of Badacsony. It is a small addendum that the mountain's silhouette will forever testify of where the basalt for the streets of Budapest was quarried between 1949 and 1954 by the inhabitants of the Badacsonytördemic prison camp.

The sets photographed by Kovalovszky are even more exciting though. He worked on his two-part series for two years: the one entitled “Black Hole” is about elderly political prisoners, and the part entitled “Inheritance” is about the children of those who were once important players within the communist party or state leadership, but became victims of show trials. The photos show old or very old people (some of whom have died since being photographed) on carefully lit photographs. There is no background, nothing to distract from the face – almost as if they were all in some idealized afterlife.

Kovalovszky visited all the locations where those convicted in the fourties and fifties spent their days. He went to prisons and courts which are still functioning today, and took a closer look at the rooms which have preserved the atmosphere of the mid-twentieth century. He photographed unchanged prison doors, fences, walls, window frames, spyholes, stages, barbed wires – things which those imprisoned in the fifties saw daily. His goal was to find the last traces and the last living witnesses of the injustices of the fifties.

Anyone expecting dark toned images to match the subject is wrong. These photos are – as I have already said – the exact opposite of the heavy, confusing times they tell us about: they are bright, clear, transparent, almost otherworldly.

“The shabby, sterile world of the photographs helps to separate the subject from the reality of the present and evoke the mood of the time” – the author, who also had a grandfather, says of his work. Although his grandpa did not spend time in prison, when he was still courting his future wife, he had a rival: a young ÁVH (Államvédelmi Hatóság = State Protection Authority – the secret service of the People's Republic of Hungary from 1945 until 1956) officer. When the photographer’s future grandmother told him that she had already made a decision and does not wish to go on with the officer, he mentioned that he will gladly help “get rid of” his rival – who later became Dániel Kovalovszky’s grandfather.

A view of Badacsony hill and the former labour camp.

The labour-camp in Badacsonytördemic operated between 1949-1954. Given that the authorities at the time made sure to cover up as many traces as possible, very few documents survived. During the Rákosi-era for many years this was the place that supplied the basalt blocks needed in Budapest. The silhouette of the mountain clearly shows how much of it was illegally extracted. The mine was closed in 1960 and afterwards the whole mountain was declared a landscape conservation area.

A prison door from the era at “Csillag prison” in Szeged.

A dark vault carved into a rock inside the dungeon in Veszprém at level -3. They mostly held imprisoned clergymen here.

Portrait of former political prisoner János Straub. János spent a total of 16 years and two months in prison. During this time he was under strict custody for 180 days, and spent 180 days in a dark vault. He was convicted in a show trial for attempting to cross the border illegally, taking part in the 1956 revolution and for multiple counts of attempted murder. He was released in 1971.

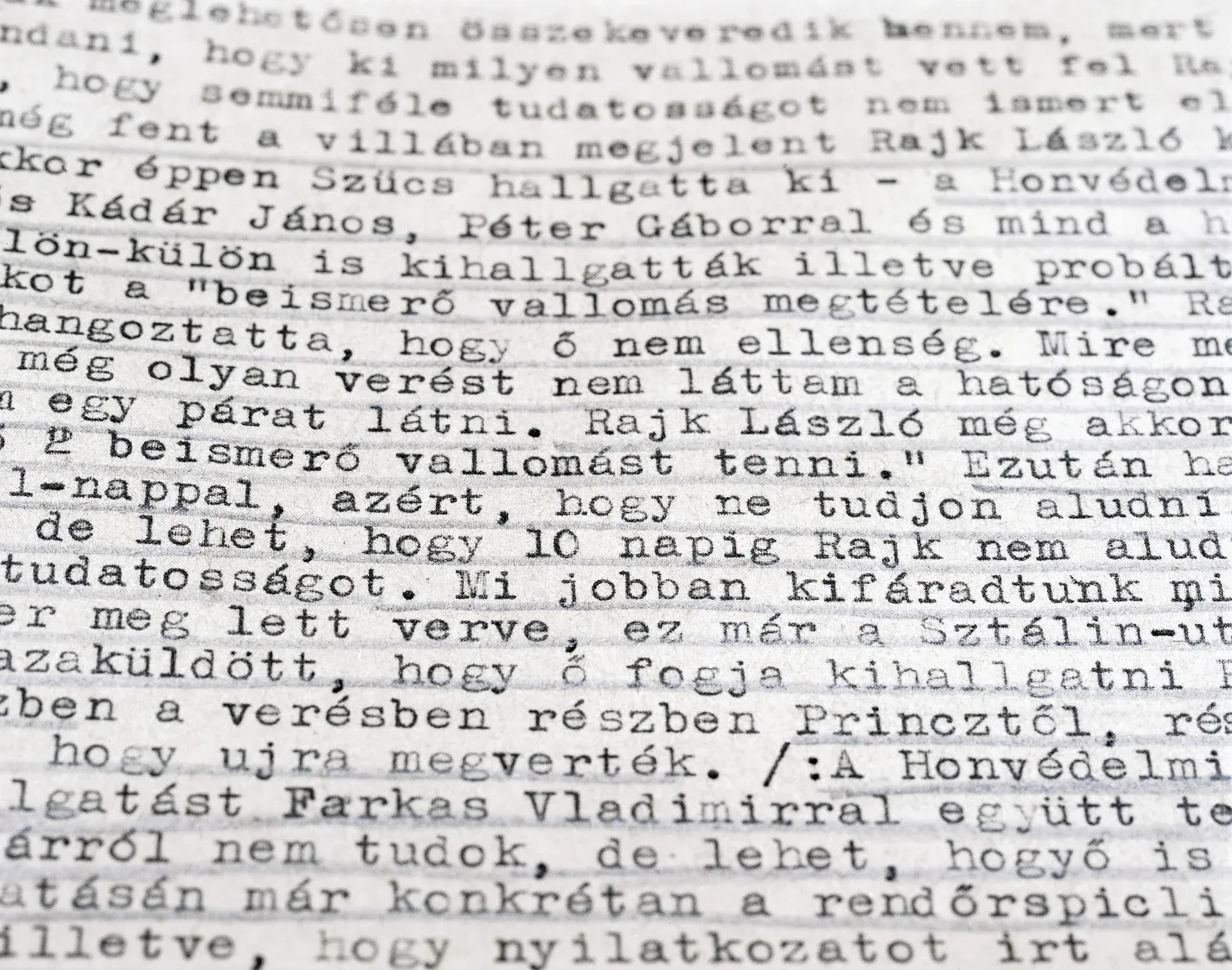

An original extract from the court record of László Rajk’s interrogation. (source: ÁBTL)

"In the first week he broke down due to psychological pressure, exhaustion and torture, and has made incriminating statements.”

The location of the camp at lower-Recsk today, east of Recsk, on the left side of the road leading to Sirok. Approximately 160-170 inmates worked here.

The gallows at “Kisfogház” (Small Detention House). Following the suppression of the 1956 revolution, between November 1956 and 1963, about 26 000 individuals were sentenced to shorter or longer prison sentences or to death. The death sentences were mostly carried out in the yard of “Kisfogház”. This is where Imre Nagy and his companions were executed in the early morning hours of 16 June, 1958.

Portrait of former political prisoner, Ferenc Balogh.

Ferenc was a 23-year old university student when he was arrested in 1951. His arrest happened ten days before his planned wedding with his then-fiancée. He was accused of organizing catholic youth camps. He spent two years at the Kistarcsa internment camp, and his parents knew nothing of their son’s whereabouts for a long time. He was released in 1953, after Imre Nagy ordered the closure of all internment camps and work camps. After his release he married his fiancée, who was – as a result – immediately kicked out of university.

A quote from Ferenc:

“The ÁVH arrested me at 2 am on 11 May, 1951. One does not forget that. I was questioned for three months day and night. Afterwards they made me sign my internment document. At first I didn’t want to sign it, but I saw that if I don’t do it, they will beat my head to pieces. They beat my head against the wall, and kept kicking me. When I was in the cell, I had to lie motionless, because if you moved, they made you get up and hold a sharpened pencil against the wall – with your forehead.”

A detail of the former prison camp in Csolnok.

Portrait of painter and tapestry artist, Katalin Jánosi. Katalin is the granddaughter of communist politician and prime minister Imre Nagy.

In the short time of his first premiership, Imre Nagy created and tried to implement the only positive economic and political programme of the era. He closed all the internment and forced labour camps and curbed the all-out rampage of the State Protection Authority (ÁVH) by merging it with the Ministry of Interior. The reviewing of show trials and the rehabilitation of those who were innocently convicted or executed had begun. He also stopped the forced relocations and announced religious tolerance.

The location where the Tiszalök labour camp used to be. The area is an agricultural area today.

The Tiszalök internment camp operated between 1951-1953. It was established with the goal of building a dam and a hydroelectric power station. The prisoners were mostly POWs handed over to ÁVH by the Soviet authorities in December 1950 and the beginning of 1951 whom ÁVH did not release. Most of the captives were Germans (Schwaben who had joined the Waffen SS during the 2nd WW).

The facade of the Markó street prison. After 1945, the Markó street prison became the center of the people’s democratic justice system. It was here that war crimes against the people were tried, and death sentence convictions were passed. Among others, former prime ministers Ferenc Szálasi and Béla Imrédi were both executed here. By 1946, the prison was so full that there were between 1800-2000 prisoners in the building originally designed for 700. They often held between 30-35 prisoners in a cell intended for 6-7 people.

The cells were infested with lice and bed bugs, and the overcrowding made their eradication impossible.

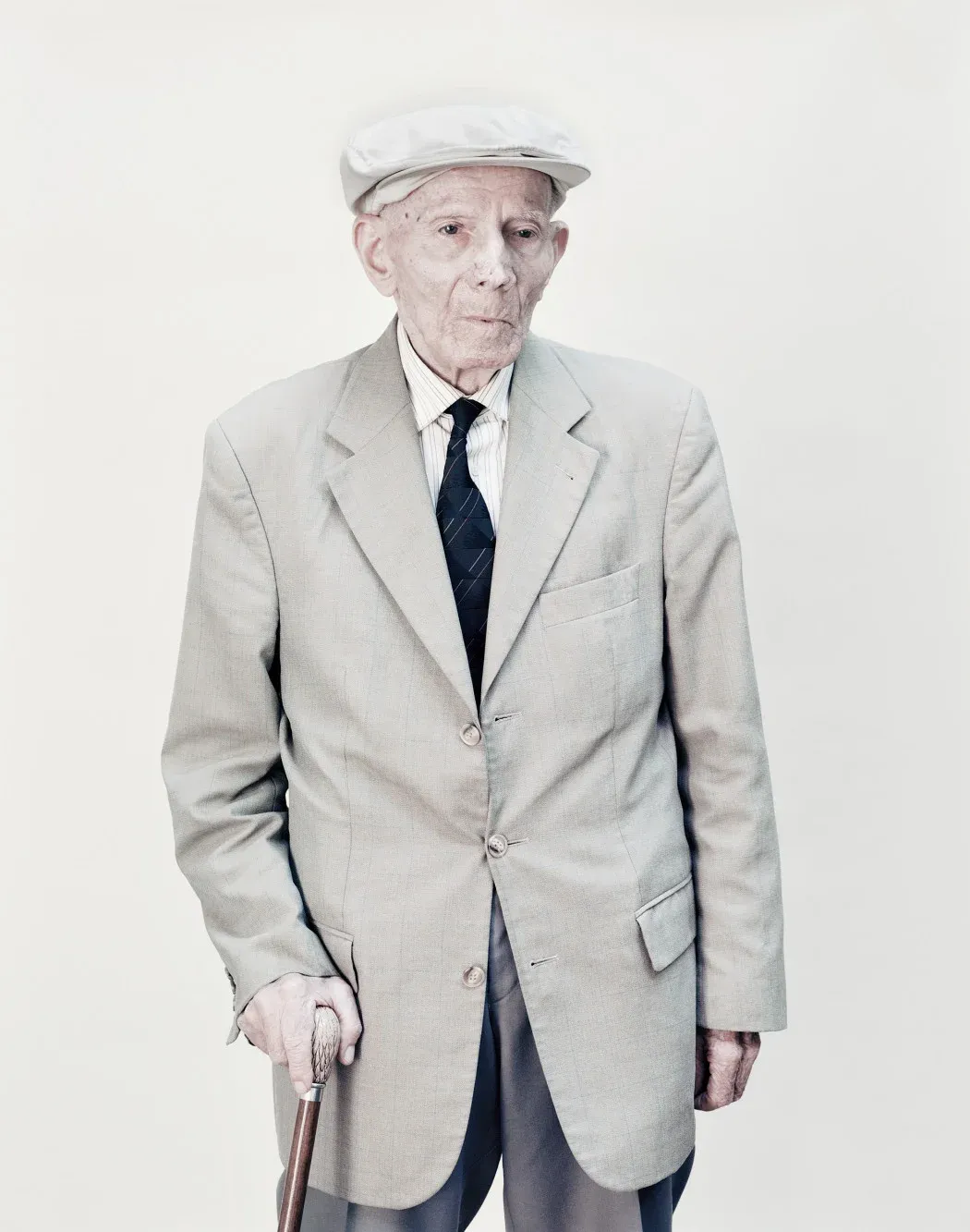

Portrait of political prisoner Ottó Békei Koós.

The location of the Rajk-Brankov show trial at the Vasas headquarters in Magdolna street. This is where the judges’ bench stood.