The oldest olympic champion of the world, the 101 year-old Ágnes Keleti is feeling well: she exercises every day, and she can still do the splits. Her son says that her decision to move back to Budapest from Israel in the 2000’s, definitely extended her life.

Many famous athletes' career was determined by a coincidence in their early life. Ágnes Keleti wanted to be a cellist. She was so talented that she had even played at the Hungarian music academy, but at a Christmas program in her high school years, she made a mistake. She was supposed to play Saint Saens’ “The Swan” when she suddenly froze and was unable to continue. Had this not happened, she might have played in a symphonic orchestra or might have become one of the country’s best cellists.

Instead, she became one of the most successful athletes of her time, and her name is known all over the world. If she had been a bit luckier, she would most likely have more than five olympic golds in her cabinet – she might have collected up to 8 gold medals in total. Even five gold medals is no mean feat, and to this day there is no other Hungarian athlete who won four gold medals at a single Olympics. It is a strange twist of history that her success was not truly celebrated at the time, as after 1956 she didn’t step on Hungarian soil until 1983, and she is barely known in her homeland.

She started practicing gymnastics at the age of 16 – at first only for her own entertainment. That is, until Zoltán Dückstein, a respected trainer of the day noticed her. In 1940, at the age of 20, Keleti was already the Hungarian champion. If the Olympics had been held that year, she would have been part of the national team – had she been allowed to compete in spite of the Hungarian law at the time, which forbade Jews from doing such things. Due to her Jewish descent, the years that followed were not about sport, but survival.

Fighting for survival

She became an apprentice at a furrier’s and even worked in an ammunition factory – she applied every trick in the book to ensure her survival. She did not wear the stigmatizing yellow star on her chest, but gave all her money and valuables for the papers of a Piroska Juhász. She watched as the Hungarian Arrow Cross (the Hungarian far-right ultranationalists) took away her uncle and cousin. It was then that she knew for sure: the fake papers may save her life. Her well-off father, who was part-owner of a factory, died in Auschwitz.

Keleti, who was born Klein had to memorize the names of Piroska Juhász’ parents, and all the relevant data of her new persona. She knew that if she made a mistake, she would be found out, and that would equal death. In 1944 she hid in the small village of Szalkszentmárton, and even though it was risky due to the bombings and the fighting, on a few occasions she traveled to Budapest to see her husband. She became a housemaid – as it turned out, at the house of the city’s deputy commander. During the war, especially during the bombings while they hid in the basement, she often thought about gymnastics and did what she could to stay strong, thus inadvertently preparing for the life ahead.

„Two wax dolls were lying in the street: a mother and her daughter, holding hands, wearing pink nightgowns. They were frozen. We put them on the cart along with other corpses, and rolled them to the mass grave at Erzsébet square. To this day, this is the worst memory of my life” – she once said about her traumatic experience. She doesn’t like remembering this season, but as she once put it: she knows that in spite of all the horrors she witnessed, she is considered lucky. The siege of Budapest ended in January, and in spring her husband returned from the Mauthausen concentration camp weighing 33 kilograms.

By fall, one of the gyms was in good enough condition for holding trainings. They managed to get approval for the most respected coach of the time to be allowed to return from forced resettlement (at the time, the communist government forcibly resettled intellectuals considered dangerous for the system to faraway villages) and the national team was together again. When the team traveled to the 1948 London Olympics, they did so with the chance of winning, but Keleti sustained an injury. They had hoped that her torn ligament would heal in time, but that did not happen. So she watched from the stands as her team came in second behind Czechoslovakia. If she had been able to present her routines, they would have almost certainly won, and she also had a chance of winning medals individually. According to recollections, there was some scorekeeping bias at the tournament, but it made them all the more determined to return home with gold medals in 1952.

The first olympic gold

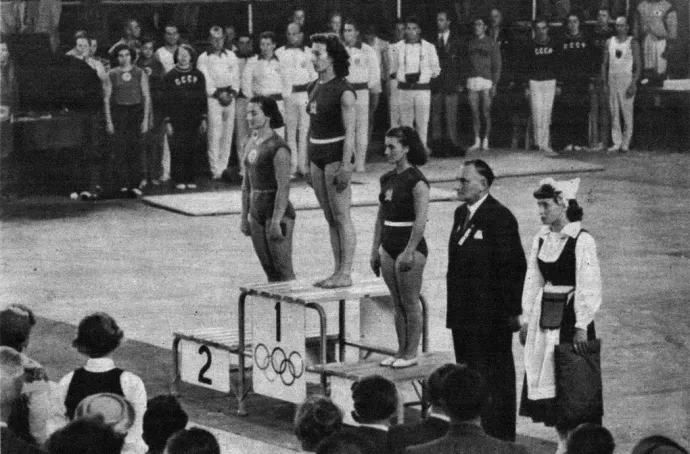

At the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki, Keleti was already 31 years old and she was determined to fulfill her dream of becoming an olympic champion. Although due to political pressure, the team was planning on allowing the Soviets to win the gold in uneven bars, Mátyás Rákosi (Hungary’s communist leader at the time) changed his mind at the last minute, and he told the team leaders to do all they could to ensure the Hungarian team’s success. Margit Korondi won the gold. In an iconic photo, Keleti is standing on the podium in third place, but even though she had just achieved the best result of her life, she is obviously not happy. A few hours later Keleti won the gold for her floor routine. Of all her gold medals, this one is dearest to her heart. She made a mistake on the balance beam, so she didn’t win a medal there, and the rhythmic gymnastics team only won a bronze because of a dropped club – which also gave them plenty of motivation for the next four years.

Retiring didn’t even cross her mind. Instead, she kept thinking about her sister Vera, – seven years her senior – who was living in Australia and whom she could see again if she were to qualify for the Melbourne Olympics. They were already planning on continuing their lives on the smallest continent along with their mother.

Four gold medals from one olympics – a Hungarian record

As they were approaching the olympic hall, she told her husband: “I didn’t sleep at all last night. Everything came back. The first time I had made it to the national team in 1938, and then all the humiliation in the years that followed. But this is about much more than that. This is my last competition”.

She concluded her last competition with four gold medals, and if she had not had one faulty jump, she would have had a fifth one in the individual all-around category as well. In spite of this, she still holds two important records:

- no other Hungarian gymnast has ever won gold at two consecutive Olympics.

- to this day she has the most (10) olympic medals (more than Krisztina Egerszegi and Danuta Kozák)

Her results are significant in the international realm as well: She is in third place in the all-time rankings of female gymnasts behind the Russian Larisa Latinyina and the Czechoslovakian Vera Caslavska, but she precedes the living legend Nadia Comaneci. While the Romanian also has five gold and three silver medals, Keleti also has two bronze medals, while Comaneci only has one. Ágnes Keleti was included in the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame with this short film:

While in Australia, she turned her back on sport and worked in a record player factory until she left the country and after a short stopover in Germany, immigrated to Israel. There she reformed the country’s gymnastics and then helped prepare the Italian team for the 1960 Olympic Games. The first time she was able to come home was in 1983 when the world championship was held in Budapest. After 1990 she started visiting Hungary more often, and moved back home at the beginning of the 2000s. Her son, Rafael believes that if it were not for all the excitement, receptions, recountings of her experience since then, she might not be alive today.

Humor, love of life, laughter.

These terms summarize her character best. A good example of humor is that she said the secret of long life is keeping the mirror far away. She said that if she doesn’t look in it, she can imagine herself however she wants. Another good example is her answer to the question: “Since you like traveling so much, where would you still like to go?” her answer: “To Heaven, but that can wait.” – was the answer. Laughter has been with her throughout her life. Once, in the nineteen-fifties, the head of the examination committee had to rebuke her for laughing so openly at something an examinee had said – given that she was part of the committee.

When her one hundredth birthday was nearing and her family had brought it up, she responded with

“Who even lives that long? Do you know how long that is?”

By now she seems to have accepted the fact that she has pulled this off as well.

(Our source for the article was the book entitled: Keleti 100 (authors: Sándor Dávid and Dezső Dobor.)

If you enjoyed this story about a remarkable Hungarian, make sure to subscribe to our newsletter to receive similar content straight in your inbox!

The translation of this article was made possible by our cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.