Making Fidesz hip, no matter the cost

- Hungarian governing party Fidesz has been trying to win more sway with the youth for years, but so far they haven’t been able to come up with a surefire outreach strategy.

- The situation came to a head after local elections last fall when the party’s commentators pointed out the defection of young voters as a contributing factor of the results.

- Since then, Fidesz has been trying harder to win over the youth: “political adjustments” were made to attract those under 30-35, and behind the scenes they’ve begun the construction of a media arsenal more ambitious than ever before.

- The resulting projects have been gradually launching since mid-2020. Both new and repositioned players backed by hundreds of millions of forints (hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of euros) in capital have emerged on the government’s side.

- This article presents what Fidesz has recently been trying to convince young voters of and how they are doing it.

- Originally published in Hungarian on 8 October, 2020. Translation contributed by Dominic Spadacene.

“We need to make young people understand that being rebellious is hip, that they don't have to follow the mainstream just because it's easier. Those who don't like conventional stuff and want to be truly rebellious and cool have no choice but to be conservative,” said István Kovács, head of the recently launched, pro-government Megafon Központ (Megaphone Center) in an interview this summer. As self-contradictory as the statement may seem, it has now effectively become an unquestionable truth within the opinion-shaping bubble aligned with Fidesz.

The administration has been trying to hammer the “being conservative = cool” idea down various channels for some time now, but their efforts on this front over the last few months have turned out to be unusually concentrated by previous standards: training a right-wing social media brigade, launching a TV channel aimed at those under 30, and releasing a redesigned, tabloid-like pro-government news site are some of the ways in which they are trying to convey the rebellious, right-wing lifestyle and other party messages. This is not merely by chance: the projects that have roots in Fidesz’s youth panic from last fall are now coming to fruition.

A high priority matter that backfired

Political parties generally already have a hard enough time winning over young people as it is, but this can be especially true for one that has been in power for over 10 years and defines itself as conservative: it simply isn’t the image that people in their teens and twenties are instinctively drawn to. Having recognized this problem, Fidesz has been trying for years to come up with a working model for attracting young voters and generating a steady flow of future successors. Naturally, the most obvious tools for this are the press and online platforms, and for at least four to five years Fidesz strategists have been seeing to it that their media portfolio contains an element which exclusively targets those under 30-35 years old. They have also been careful to build up a pro-government presence on social media.

While the youth vote issue had previously only been a blip on people’s radar, sometime after the local elections last fall the situation suddenly changed. The pro-government media was inundated with voices saying that the tools in place were insufficient, that the right was unable to engage young people (unlike the liberal-left opposition, especially the Momentum party), and this could have serious consequences. To the extent that this fear is well-grounded, we will address this question at the end of this article.

The intensifying internal dissatisfaction initially brought about some changes in personnel as well as slight changes in policy. It was quite the spectacle to see Fidesz make an effort to appoint young people (as well as women) to various positions, such as the appointment of Alexandra Szentkirályi as government spokesperson this past winter. Another example was the party's attempt to embrace environmental issues that they previously would have written off. Some of their measures met with rather ambiguous success, such as the appointment of Zsófia Rácz as Deputy State Secretary of Youth Affairs, who at the time was 22 years old and not yet graduated from university. These particular qualities required parliament to modify a law, which caused considerable backlash. In principle Rácz’s task is to address the youth in their language and convey their needs to government decision-makers. According to her Facebook page, the Deputy State Secretary diligently visits events that align with the administration’s politics (inaugurations, children's camps, a free summer university put on by a youth organization standing in close ties to Fidesz), but her activities so far have not been of much note. She doesn’t speak to the independent media, where she could in fact address the young people who are sceptical of the government, nor does she give the overall impression of the hip, casual, outspoken and relatable figure that the right so dearly lacks within its ranks.

The 888 fiasco

Of course, this sort of role doesn’t have a place in the government’s work, so following the “we are losing the youth”-panic last fall, it was only natural that they would start to incorporate more distinctive voices in the public sphere. The natural platform for such projects is online media, specifically the portion targeting those under 30-35 years old, where Fidesz had not been entirely without a voice as it were. However, four years into their first large-scale undertaking, it can be said that 888.hu did not live up to expectations.

Created under the supervision of political scientist and Fidesz strategist Gábor G. Fodor (GFG), the news portal clearly aimed at engaging young people from the very beginning: a provocative style and variety of topics, a relatively strong emphasis on video content, a heavy social media presence and a staff consisting of twenty-year-olds all could have made 888 suitable for this role, but an oversight was made somewhere along the way. Initially, the portal managed to draw attention to itself at least through scandals (shortly after its launch, the site cropped up everywhere after posting nude photos from the youth of the wife of then MSZP president, József Tóbiás). Later, however, the project, which in the meantime had been absorbed first into Mediaworks and then into KESMA (Central European Press and Media Foundation), faded into total obscurity. According to our sources, its loss of attraction is due to the fact that since the beginning of 2019 (when one of the site’s defining personalities, Gellért Oláh, resigned following a scandal involving the Nazi salute) roughly the entire staff of the site had to be replaced as a result of dissatisfaction with GFG’s leadership and the handling of the Oláh case. Presently, most of the site is populated with content by interns who upload news pieces from the MTI (a state news agency) and foreign press digests that lack authorship. The site’s informational page no longer includes the names of any journalists at all.

Even if 888 had never contributed anything else of lasting quality, they at least have always had that motto so overplayed these days (being conservative, right-wing, Fidesz as a young person is hip and rebellious): the page originally launched with the slogan “join the rebels”. Since then, the space has seen the arrival of new candidates who have a shot at success on other platforms and with far more financial support than ever before. Nevertheless, even though these projects are backed by hundreds of millions of forints (hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of euros) in capital, it still takes a pretty wild imagination to foresee Pesti TV (just to be clear: a television channel), the recently facelifted and influencer-campaign injected Origo or the right-wing social media celebrities trained by Megafon Központ obtaining a broad, twenty-year-old fan base.

Right-wing Facebook fighters take on the liberal tsunami

One of the new players on the scene is Megafon Központ, which, in addition to its intensive Facebook campaigning, has caused a stir on account of the startling amount of media coverage it received compared to other new initiatives. The founder, István Kovács, toured almost every pro-Fidesz mainstream media outlet. From Mandiner to Origó and Pesti Srácok all the way to the M1, he was interviewed everywhere. In his interviews he had the opportunity to explain the goal of the new organization: to amplify right-wing voices on social media. Megafon’s message is consistent with the administration’s narrative: although the majority of people are right-wing (or more precisely, Fidesz supporters), “conservative voices” are being suppressed in the public sphere, and despite the many years of a Fidesz-led government, liberal and left-wing speech still tends to dominate the media.

This interpretation has been a constant in the history of the party and the administration. For years, Viktor Orbán has regularly brought up the significant predominance of the left, thus legitimizing the ruling party's advances in the media industry as well as tactics like the creation of KESMA (the Central European Press and Media Foundation), which brought together more than a hundred media products. Last year, the prime minister seemed pretty much satisfied with the state of affairs when speaking of the domestic press: “maximum 60 percent is left, but it’s more like 50 percent, and 40-50 percent is Christian-conservative right.” However, there have been some developments since then (e.g. the shortened financial leash of Index or Klubrádió’s loss of its radio frequency) which suggest that the steamroller hasn’t come to a stop.

Megafon is now trying to inculcate the idea that the liberal left’s dominance is even detectable on social media (and moreover, that such content is funded by a coordinated network), and they want to help those who would stand up to it. As their website reads:

“Is the content funded by the Open Society network coming at you like a tsunami on your social media? Do you feel like doing something about it? Do you have a lot to share but just don’t know how to get started? Or perhaps have you already tried but haven’t yet been able to achieve breakthrough success? Interested in content production for Facebook, Instagram, and other online platforms?

Megafon Központ is here to help! We don’t want to tell you what your opinion should be, but we would like to make sure that your voice is heard as well!”

Megafon announced a free, four-day training session for September, which reportedly had more than two thousand registered. Kovács’s team selected the most promising 100 from among them, who were divided into six groups to take part in the social media crash course later this year. So there’s a chance we’ll come across the content of highly refined right-wing youtubers and “professional Facebook fighters” in the coming weeks.

But where are they getting the money for this? Behind Megafon stands Megafon Digitális Inkubátor Központ Nonprofit Kft. (Megafon Digital Incubator Center Nonprofit Ltd.), which was registered in May. Founder István Kovács stated in interviews that he had “sought out many businessmen” while raising financial resources. What he didn’t reveal, however, was who invested in the company (as he stated, “those in question don’t wish to attach their name or face to the fact” that they’ve invested) and just how much money is at stake. Following its launch, Megafon ran an intensive Facebook campaign, which is why we wanted to find out how much money they advertised their posts for. However, according to Facebook’s Ad Library (where all advertisement spending can be officially tracked), as of yet, the center has not run a single ad.

We wrote to the email address provided by Megafon to find out how this is possible, how much they advertised for, as well as approximately how much money they received for the project and from whom. At the time this article was published, we still had not received a response. István Kovács had previously revealed to Pesti Srácok that, at least by the time of its launch, neither István Tiborcz nor Lőrinc Mészáros had put any money into Megafon, but their donations would be warmly received if they supported the center’s goals.

Another youthful, pro-government entity that hasn’t received as much publicity but has similarly recently appeared on Facebook is Axióma Intézet (the Axiom Institute). Its associated private company and the Axióma Kulturális Alapítvány (the Axiom Cultural Foundation) were founded last year by Áron Giró-Szász, the Prime Minister's representative in charge of "tasks related to liaison and support for Christian movements and Christian communities". Axióma is less concerned about current politics and rather deals with ideological and moral issues as well as the construction of a conservative identity in a manner uncommonly moderate for pro-government media. Based on the topics it addresses (e.g. dating) and their presentation, it appears to target the more contemplative youth. Its principal activity is the production of brief animated, informational videos, in which they tend to present rather simplified versions of complex issues in a conservative light (their informational orientation is well illustrated by their video on abortion, for example), but they also occasionally present debates between Fidesz and the opposition on various divisive topics. Since producing such content is a labor-intensive undertaking, we inquired at Axióma about where its funding comes from. When asked about their financing, the institute wrote that as a private foundation, they sustain themselves via private donations. “We are in no way connected to nor conduct any business with the state or any politically involved organization. In order to carry out our work, we prefer to focus intently on community funding,” they wrote.

Winning young people over with TV ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

The flagship and largest investment of the Fidesz youth project is clearly Pesti TV, which after much preparation launched on September 14. With the fading of 888, the team at Pesti Srácok have begun to emerge as a prickly editorial staff quite vigorously targeting the under-35 age group. On its own, however, PS doesn’t fit the bill as a high-impact outlet capable of carrying out the full-court press that’s in the works. Its daily level of engagement is similar to that of 888 at about 30-40 thousand users. Their content, on the other hand, is more often is able to incite discussion on online platforms (in terms of reviews and enthusiastic or outraged Facebook reactions), and several of their contributors have already tried their hand at TV (e.g. on Hír TV’s “Keménymag” [Hardcore] or “Informátor” [The Informant]), so it might have seemed like a logical move to shift in the direction of video.

One thing that remains a mystery, however, is why Fidesz expects a TV channel to be effective in engaging young people in the year 2020.

Although Pesti TV can be watched online, it does not have an official account on the platform most adored by those in their teens and twenties: YouTube. Instead, its content is uploaded on various accounts that are not clearly identifiable (this is presumably related to the fact that YouTube doesn’t allow Pesti Srácok to register on its site since the incident involving a blurred pedophilic video published to illustrate an article). The primarily TV-based model, even with an online presence, may prove to be a barrier to increasing engagement in an age group that practically doesn’t watch TV at all, even simply for the kinds of shows it offers. After the channel’s launch, it seems that despite their efforts and self-definition of “#influencer television”, the channel’s content didn’t prove to be that appealing to the youth: its backbone consists of lifestyle-oriented studio programs and talk shows, into which they try to smuggle topics that appeal to those in their teens and twenties (for example, several programs plan to include exchanges with influencers, and there is also talk of a show for gamers), but at the end of the day, the shows can’t escape their studio feel. That is not to say that the genre of people talking about something (+ a few video clips) is bad in and of itself. A significant portion of Youtube is indeed made up of such content. An important ingredient, however, is that the participants, having organically grown their own fanbase, are addressing first and foremost their own followers, and further, that the entire setup is much more casual than any sort of TV format.

For now it remains uncertain how this resuscitation of classic TV genres and Pesti TV’s image design will pan out in this arena in the long run, but based on its initial broadcasts, the project doesn’t appear that compelling (bold, defiant, etc.), and that’s putting it mildly. Without turning this article into a TV critic’s commentary, here are some of the shows along with their brief summaries from the channel’s website:

- Boomer Rebellion: “Young versus old: different generations around a table battling it out on various topics. On this show, our older, wiser counterparts are faced with issues that interest and affect young people. Traditional, right-wing values, past affairs and events having historical significance, meanwhile, also get to have a say in the matter. Substantive, youthful, fundamental, value-imparting. This is the Boomer Rebellion!”

- Crocodile Brain: “The countryside rebellion with Szabolcs Fábry. On this show, we counter with our most resolute, hardest-hitting responses to the mudslinging liberal-left and their opinion leaders, who consider the right-wing voting countryside obtuse, “crocodile-brained”, indiscriminate good-for-nothings. Szabolcs Fábry and his guests take up the gauntlet and settle the score!”

- Who ate the missionary?: “‘Because the spread of democracy sometimes encounters unexpected difficulties…’ ‘Who ate the missionary?’ is the parade of irony and memes on Pesti TV, where, with a pen dipped in sarcasm and a sharp tongue, we dissect the memes and political content enjoyed by young people that have spread like viruses on social media and the broader Internet. Right-wing publicists versus memes and the youngest generation. Dóra Zelenka and Botond Bálint are in the studio.”

- The Sane Rebellion: “A Pesti TV program about public figures that raises its voice against abnormality and takes a stand for normality. We present the emerging opinion leaders of the Hungarian right who are taking a stand on social media and demanding that their voices be heard. This is the show where we face off with the liberal-left mainstream, where we don’t allow the liberal elite to determine what the norm is, how to think, and who we have to adjust to. This is your place – rise up with us!”

The question of financing in the case of Pesti TV is even more intriguing, as television is a more expensive genre than running a newspaper or managing social media, even if it's a low-budget studio. Based on the estimates of our industry sources, the launch of a channel of this calibre, when all costs are taken into account, could fall between 800-1000 million forints (2-3 million euros).

One of the owners of the channel’s production company, Progress Media Hungary Ltd, is Miklós Vaszily, a media manager with ties to the government. With that said, one thing is for sure: substantial capital was invested into the project by the other owner, a trustee who manages Lőrinc Mészáros’s money. As reported by G7,

Bizalom Vagyonkezelő (Trust Asset Management Company) has invested 500 million forints (almost 1.4 million euros) in Progress Media, which is likely what Pesti TV is tapping into at this point.

Whether they had any other significant start-up costs apart from the construction of the studio and acquisition of equipment, it cannot be said for sure, but according to our industry sources, it can cost 280-300 million forints (750,000-825,000 euros) in order to be included in Antenna Hungária MinDigTV’s package. The opposite is true with cable TV providers, who are still the ones to pay national channels a larger sum in order to keep them in their basic package. In the TV2-RTL Klub tier, this is around 600 forints (around €1.70) per user per month for the complete package, but even the smaller commercial channels can ask for 100-120 forints (around €0.30). As far as we know, Pesti TV offered itself for free compared to this, so naturally they didn’t have a hard time getting into the package, especially considering the fact that in Hungary these days it wouldn’t seem like a wise decision to turn down a channel backed by Lőrinc Mészáros’s money. We asked the director of Progress Media Ltd. about the arrangement under which they were included in the basic packages, to which Gergely Kovács, managing director, replied that contracts are trade secrets, so he cannot provide information about the kind of agreement that has been concluded with broadcasters.

In terms of financing, a more compelling question is whether Pesti TV can generate enough revenue from advertising to cover its constant operating costs and, if not (or if just by artificially pumping in state advertisements), whether it will be able to deliver results that make it worth operating for Fidesz.

With the Hír TV – Echo TV merger, it became apparent that although the government media pocketbook seems endless from the outside, in reality, efficacy considerations sometimes prevail.

Against this background, the launch of the new television project was somewhat surprising, and it can be safely assumed that something will be expected from it in exchange for long-term support: first and foremost, that it shows itself to be capable of fortifying the young Fidesz base. With regard to market-based financial returns, it’s not reassuring that in the days following its launch, Pesti TV's audience share in the 18-59 age group ranged from 0.06 to 0.2 percent according to Nielsen. Based on statistics from September 23, an average of 1395 people over the age of 4 were watching the channel every minute (for comparison, TV2 lead that day with a number of 171,000).

Origo’s awkward makeover campaign

Even during the time before the government’s influence, Origo, which was acquired in 2015 by businesses with ties to Fidesz, was not well known for its youthful content. It was considered among the moderate news portals striving for objectivity. Ever since the publication was fully integrated into the pro-government communications apparatus in 2016, it has possibly shifted even further away from engaging the under 30-35 age group – that is, if it weren’t for the tabloid articles that run in prominent places on Origo’s front page and even appear on its Facebook page. It appears that the media strategists of KESMA and Fidesz wish to change the image, as Origo underwent a complete redesign in early September, and in all respects it tries to suggest that the site offers fresh, colorful, light and fashionable content. Unlike the previous two examples, here they aren’t trying to push the convoluted “be pro-government: rebel against the mainstream” message. Rather, they just suggest that Origo is neutral and entertaining – a website that anybody can get into.

The teaser campaign for the new design is also conspicuously aimed at young people. Origo banners have been running on other Fidesz platforms for weeks, and they’ve also prepared stock-photo-like promotional images and at least one advertisement spot.

However, these aren’t what backfired, but rather the campaign’s most modern tactic: influencer marketing. Someone at Origo’s advertising agency thought it would be a good idea to ask Instagram celebrities to advertise the news site, but this campaign strategy likely ended up doing more harm than good. Besides #origo, the paid posts (including those of Adrienn “Viva” Pintér, Rebeka Markó, the youtuber by the name Unfield, who later deleted his post, and Tímea “Miss Hungary” Gelencsér) were tagged with #ujatmutatunk (lit. “we’re presenting something new”). This gave an idea to those who were irritated by Origo’s advertising about how to disrupt the campaign: soon enough, Instagram was flooded by middle finger emojis directed at Origo underneath the hashtags. [translator’s note: the response plays off the pun “ujjat mutatunk”, meaning “we’re showing the finger”, calling to mind Origo’s original hashtag.] And yet the misfired advertisement stunt could not have been cheap either. According to a source familiar with influencer marketing, a paid Instapost is valued at roughly 3-6 forints (1-2 euro cents) per follower, so advertising on profiles with hundreds of thousands of followers can amount to millions of forints (thousands of euros).

The under-30 Fidesz base: weakened but still strong

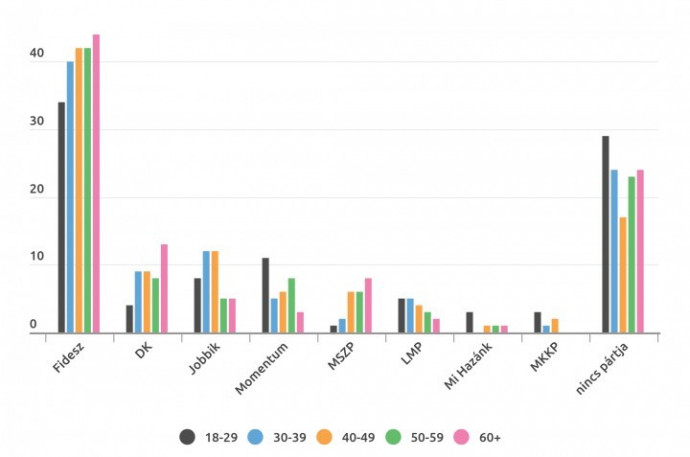

But does the ruling party really have any reason to fear that its power could waver in 2022 because of younger voters? If you take a look at the numbers, it is truly apparent that

on the one hand, Fidesz is significantly weaker with the 18-29 age group than with the older ones; on the other hand, the ruling party is still by far the strongest with this age group as well.

In the 2018 parliamentary elections, Fidesz received 49 percent nationwide, but among voters under 30, it only managed 37 percent. There is no truly fresh data on the subject, but at the time of Medián’s spring survey, Fidesz was strongest among the oldest voters, those over 60 (at 44 percent), while among the youngest group, those under 30, it received only 34 percent. Although the difference between the two values does not look good for the ruling party, it is worth adding that no other party has been able to approach this amount. Standing second among the youth, even Momentum only managed to gather 11 percent. Meanwhile, the proportion of those who are uncertain is largest among those under 30 (29 percent), which could mean that well-targeted messages still might earn a number of voters in this category.

Party support by age groups, March 2020:

If we consider those between the ages of 18 and 35 as the youth vote, about 1.9 million people will fall into this group for the 2022 election. No political party can afford to pass on this demographic, so for the next year and a half, these voters will certainly be seeing a great deal of political messages from all sides. However, even when considered together, the parties making up the opposition will not have as much funds to address young people as Fidesz. To the extent that the project to build a cool and rebellious Fidesz image using the tools described in this article is successful, we will find out by the next parliamentary elections at the latest. It may even be more than enough for the ruling party to halt the erosion of its popularity and carry its 2018 numbers in the targeted age group. But considering the quality we’ve seen so far, it could easily be the case that even if they succeed, it will not be thanks to the propaganda aimed at young people, no matter how much money they pour into it.

We asked Fidesz’s press division to explain why they’ve been reaching out so actively to young people in right-wing media lately, and whether this is related to the fact that many Fidesz opinion leaders talked about having lost touch with young people following last year’s local elections. We also asked whether there was an appeal to entrepreneurs associated with the party to support right-wing media aimed at young people, and how, according to their own measurements, the party’s support now stands among voters aged 18-29. At the time this article was published, we still had not received a response.

(Title page and cover image illustration: szarvas / Telex)