Although pandemic deniers are always louder than the silent majority, most people respect the guidelines regarding mask wearing and social distancing, and believe in the purpose of them as well. However, in terms of the most important factor regarding the spread of the disease, i.e. the number of social contacts, we are much worse off than we were in the spring. Moreover, Hungary is very much divided when it comes to vaccination. Find out the latest research regarding the pandemic here at Telex. Translated by Dominic Spadacene.

Although pandemic deniers are always louder than the silent majority, most people respect the guidelines regarding mask wearing and social distancing, and believe in the purpose of them as well. However, in terms of the most important factor regarding the spread of the disease, i.e. the number of social contacts, we are much worse off than we were in the spring. Moreover, Hungary is very much divided when it comes to vaccination. Find out the latest research regarding the pandemic here at Telex.

Nearly five percent of Hungarians have been tested for the coronavirus so far, but according to a recent national survey few have direct acquaintances who were infected: by the end of September, only 0.7 percent of those surveyed had had a family member with COVID. However, given the popularity of certain pandemic deniers (viral realists, as they call themselves) or the often overwhelming outrage found under coronavirus-related news articles, it might seem that by the second wave Hungary has basically terminated the social contract that helped keep the pandemic under control in the spring. It is clear that in early autumn, after people had loosened up over the summer, the public mood about the necessary measures had changed. Citing this and the preservation of the economy, the government has also loosened its grip on the reins.

However, based on nationally representative data from recent research the situation does not seem to be so bad when it comes to peoples’ attitudes. According to the survey, 86 percent of people wear a mask or respect social distancing when in an enclosed space. 92 percent of those who take such precautions believe that they can protect themselves to some extent from the virus by doing so, and even more are hopeful that such measures help them to protect their environment from contamination. The vast majority, therefore, believe in the fuzzier rules of self-regulation, mask wearing, and social distancing.

Pandemic Forecasters

Telex is the first to publish new data from nationally representative surveys of the MASZK epidemiological modeling group at the Bolyai Institute of the University of Szeged, led by Gergely Röst. Röst’s team has been often featured in the media in recent months, as they are the ones providing the government with analyses of the possible courses that the pandemic might take. Although Orban’s administration is reportedly paying less attention to researchers and is more consumed by economic and political considerations since fall started, the group remains the country’s number one domestic source of information regarding the expected evolution of the coronavirus situation.

The model’s aim is to predict the spread of the virus as accurately as possible, which is essentially determined by the number of social contacts. It is also the starting point for Alessandro Vespignani, one of the most renowned experts on virus propagation in the world today. The Italian scientist began constructing a system 15 years ago that is projected to be able to predict the spread of viruses in the same way that meteorology predicts the weather.

Among other things, his scenario analysis is now used in the USA as well, and he continued his postdoctoral research in Boston with the Hungarian Márton Karsai (Associate Professor of CEU), who is responsible for social research related to the coronavirus in the MASZK group together with Júlia Koltai (Institute of Social Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Eötvös Loránd University, CEU). People’s behavior during the pandemic is continuously examined using nationally representative samples and online questionnaires (the MASZK online questionnaire can be filled out here, which also helps Hungary’s efforts against the spread of the disease). Last but not least, the change in the number of social contacts is also monitored, which is a key issue according to scientific literature. This is what dropped radically in Hungary back in March, when the coronavirus appeared in the country and strict restrictive measures were quickly adopted.

Keep a safe distance!

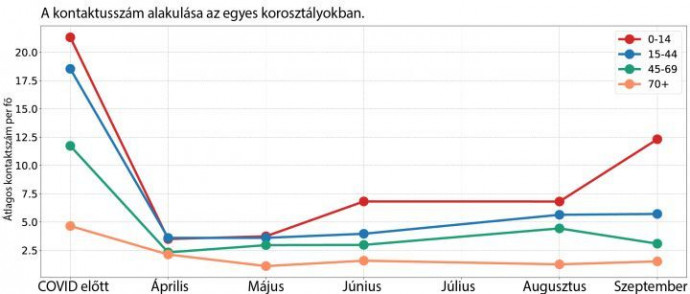

In the graph below, it’s not so much the numbers themselves that are interesting (they are based on self-reported questionnaire data, which has an inevitable margin of error) but rather the emerging trend. Compared to pre-COVID times, the number of social interactions fell by 90 percent in March and April. As the situation started to lighten up during the summer, the number began to bounce back but still remained well below previous levels. By September, with the start of school on the horizon, it started to take off among children.

Prior to the outbreak, people came into contact with an average of six people per day for at least 15 minutes within the critical distance, excluding individuals in their household. It dropped to barely half that in March, which is to say that people were quick to isolate themselves at home during the first wave. “Mid-May was the turning point – people were very disciplined up until then. Then in the summer they started to loosen up more and more: there was a good 30 percent increase from June to August, and at the beginning of September the average number of contacts jumped by another 60 percent,” reported Márton Karsai to Telex.

“The overall picture that emerges from the data is that people went away on vacation, came home, and spread the infection all across the country,” adds Júlia Koltai. According to researchers “it wasn’t the start of the school year that caused the second wave, although it did provide the wave a tremendous boost. It is much more difficult to control the situation as it is now more of a community-based infection, rather than one limited to institutions. And the higher number of contacts reinforces that.”

An often cited aspect of the second wave is that it began its spread among young people, from where the average age of those infected is now creeping up. The MASZK questionnaires also show that it was mainly younger people who traveled during the summer: seven percent of those surveyed traveled outside of the country in July and August, most of them in their forties (12 percent of them) or young adults (10 percent). The number of social contacts among the elderly is still much lower than prior to the pandemic, but it is not a good sign that it is starting to rise as well. In this respect, encounters between the elderly and the young are particularly serious, and this number has also increased during the time leading up to September.

“In terms of contact, we are doing nowhere near as well as we were doing in March. It’s surreal how much more vigilant we were about taking precautions when the infection rate was much lower compared to now. It’s also a question of objective educational constraints: schools were closed then, and many people were working from home. The border lockdown and the 11pm-curfew for bars will be much less effective at controlling social contact,” said Júlia Koltai.

Exemplary mask discipline

The latest round of questionnaire research regarding the pandemic was finished in late September. At that time, six out of ten respondents said that during the preceding period they had been in an enclosed space with people outside of their household. More than half of them also claimed to have worn a mask and kept their distance. Nearly a quarter of them only wore a mask, and a tenth of them only kept their distance; so in total, 86 percent of them took some sort of precaution. One in seven believes that they can completely protect themselves from infection in this manner, while half believe that it’s effective only to a great extent, and 28 percent believe even less so. Compared to this total of 92 percent, an even greater amount, 95 percent, say that the precautions they take can protect their environment to some extent from becoming infected.

So most people have confidence in masks, but the minority who admit to not taking any precautions at all, justify doing so mostly due to a lack of confidence in the masks or because they find them uncomfortable. Nevertheless, the overall situation regarding mask wearing is much better than it was in the spring. (To be fair, not even Hungary’s Operational Group defended masks at that time.) Interestingly, there is not a real correlation between level of education and attitude towards mask wearing. The majority of all social strata seem quite disciplined, with women slightly more so than men.

How do they know?

The questions of the Hungarian Data Reporting Questionnaire (MASZK) are examined in two forms: an online questionnaire (accessible at this link) which shows behavioral changes in virtually real time, as well as a monthly survey of a nationally representative sample of the population. The researchers draw conclusions based on the results of the questionnaires, which are similar in content, getting the best out of the two methods. The research is led by Márton Karsai, Associate Professor of the Department of Network and Data Science of CEU and Júlia Koltai, research fellow at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Centre for Social Sciences, assistant professor at the ELTE Faculty of Social Sciences, and visiting lecturer at CEU. The research group also includes Orsolya Vásárhelyi (CEU, University of Warwick).

Many people are apprehensive about vaccination

When it comes to a future Covid-19 vaccine, the picture is reversed: based on their current understanding, more men would vaccinate themselves than women. Overall, however, there is a great deal of uncertainty regarding the matter of a vaccine, and until September this has only increased among Hungarians. There are many more unknowns about coronavirus vaccination than with a traditional vaccine that has already been established.

This is, for the most part, simply due to the fact that a vaccine still does not exist to this day. In comparison to the standard development process, the radically accelerated pace might cause apprehension among many regarding the extent to which the technical safety protocol will apply. Even the expected duration of protection is not clear, so the issue is much more divisive in every country compared to usual vaccination opposition.

Commissioned by the World Economic Forum, Ipsos has already conducted a global survey on the subject in August, according to the results of which 74 percent of the world’s population (in fact, only 27 countries were included in the survey) would vaccinate themselves. However, large differences were apparent between the countries. While China stood at one end of the spectrum (97% willing to vaccinate), nations in our region stood at the other: following Russia and Poland, more people in Hungary said they did not want to be vaccinated against coronavirus (44% compared to 56% willing to vaccinate) than in any other country surveyed.

This coincides with the results of the Hungarian questionnaire research designed for pandemic modeling. According to the latest data compiled in September, a quarter of the people in Hungary would get the vaccine immediately, and a further two out of every ten would do so after some time (most of the latter would wait at most three months). More than a third of respondents (37%) would not vaccinate themselves, and roughly 20 percent are still uncertain about the issue. An even smaller proportion of parents would vaccinate their children: 18% would do so immediately, followed by another 18% who would do so after some time; all the while, almost half of parents (46%) would not vaccinate their children at all.

Despite the arrival of the second wave, the proportion of those who are for the vaccine fell further following August, and the number of those who are uncertain increased dramatically (a month earlier they made up only 8 percent, so it is two-and-a-half times its previous value). Willingness to vaccinate is greater among those with chronic diseases, residents of Budapest, and those with a college degree, and it is lower among residents of small towns.

At the same time, the popularity of the flu vaccine has grown significantly. A separate campaign is raising awareness about the danger of simultaneous outbreaks of two epidemics as well as the free flu vaccine promised to be ready by the second half of October. As a result, already 27 percent of respondents say they would like to get the shot, whereas only 16 percent of people recalled to have been vaccinated against the flu last year.

This is important; however, in terms of the course that Covid-19 will take in Hungary and future restrictive measures, the crucial questions are: when will there be a coronavirus vaccine, how will the public’s attitude towards it change going forward, and how will our behavior evolve in the meantime? Because of the moderately effective governmental measures, it is now even more true that our health and that of our environment depend largely on us.

This article is the translation of the following Hungarian publications:

„A magyarok többsége nem akarja beoltatni magát Covid ellen” – published by Telex on 05/10/2020

(Cover image: A doctor wearing protective equipment cares for a patient in a ward set up to receive patients infected with the coronavirus at the capital’s St. László Hospital on May 8, 2020.)