As Hungary lauds its 'Eastern Opening' policy, statistics fail to show benefits

May 07. 2021. – 01:06 PM

updated

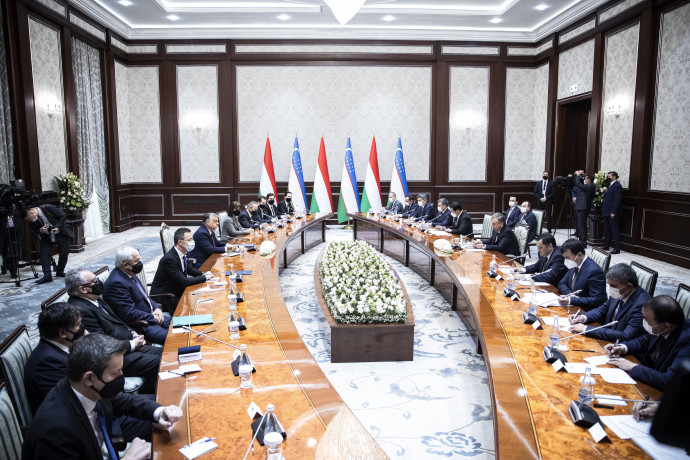

We are entering a new era (in the history) of the world economy. The government’s Eastern Opening policy, launched eleven years ago, has contributed significantly to Hungary being among the winners. This strategy is aimed at building the strongest relationship possible with Eastern economies, which are the fastest growing economies in the world

– said Péter Szijjártó in late March on a visit to Uzbekistan. During the same visit, the Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán visited the Uzbek-Hungarian Scientific Potato Research Center in Tashkent, presumably a cornerstone of the strong economic ties mentioned by Szijjártó.

This sort of rhetoric has been a mainstay of Hungarian foreign policy since Fidesz’s ascent to power in 2010. In speeches even before the 2010 election, Orbán asserted that “Eastern winds are blowing” in the world. The Hungarian economy is heavily reliant on Western capital and demand, whereas the West, according to Orbán, is in economic and political decline. Hence, in order to safeguard Hungary’s development, the country should reorient itself towards Eastern markets, so the theory goes.

This idea is far from radical: from Germany to Serbia, many European countries pursue trade and investment opportunities in rapidly growing East Asian economies. Following the “winds” of the world economy is especially important for a country like Hungary: a small, open economy, which, for better or worse, had been pinning its economic development on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and trade since the fall of socialism in 1989, and has ended up being one of the most trade dependent countries of the world.

But while the Orbán government invested considerable political capital into cozying up with Eastern regimes, going so far as to veto European Union (EU) statements condemning human rights abuses in China and elsewhere, the economic gains of the Eastern Opening appear non-existent:

Hungary’s economic reliance on the EU has not changed since 2010, and the promised Eastern opportunities have never materialized.

Data do not lie

Trade statistics offer a sobering contrast to Szijjártó’s rhetoric. Emerging Asian economies absorbed only 2.4 per cent of Hungarian exports in 2020 – the exact same amount as in 2010. The Chinese export share shows a similar story: it went from 1.6 per cent in 2010 to only 1.7 per cent in 2020.

In contrast, Hungary’s reliance on exports to the European Union grew in the same period, from 73 per cent in 2010 to 77.3 per cent in 2020.

Due to the combination of lacklustre exports and modestly rising imports, Hungary’s trade balance with East Asia has been worsening in recent years. And while Hungarian exporters are in the red with the East, they are running a growing surplus with the EU.

In light of the abysmal trade data, Péter Szijjártó has recently been focusing on rising Eastern investment in Hungary. In a Facebook post last December, the foreign minister wrote that “we have never had such a successful year in terms of investment.” In another post, he said that China was the primary source of new direct investment in Hungary in 2020, while South Korea was the leading foreign investor in 2019. He also claimed that “almost half (48 per cent) of the cumulative value of large investment projects are linked to companies from Eastern countries – China, Korea, Japan and India”.

The national accounts appear to suggest otherwise. According to data from the National Bank of Hungary, the majority of the FDI stock in Hungary is held by companies located in the EU; and their share in the total FDI stock had actually grown between 2014 and 2018, the latest year for which data based on the location of the ultimate investor is available.

When it comes to FDI inflows, the relative importance of Asian investment has been on the rise since 2018, but not for the right reasons. While the value of investment coming from Asia has remained constant at around a billion euros for each year between 2018 and 2020, the inflows from Europe and the Americas shrank considerably. In 2020 alone, German investors repatriated (or wrote off) 1.9 billion euros worth of FDI, while in the previous year, Hungary registered an outflow of 1 billion euros towards the Americas.

In other words, investment has been drying up. While according to Szijjártó 2020 was Hungary's best year in terms of foreign investment, the national accounts show that FDI inflows were at their lowest since 2015. Based on the same dataset, China was far from the largest investor in 2020: only 2 per cent of FDI inflows came from the mainland, and a further 9.6 per cent from Hong Kong.

We have asked the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade about the disparities between the national accounts and Szijjártó’s Facebook posts, but have received no reply.

There are a few possible explanations for Szijjártó's claim, albeit open source data does not support these.

First, most of the FDI in Hungary is held by multinational companies, which often carry out their Hungarian investment activities either through a Western European subsidiary, or a special purpose vehicle based in a tax haven. This complicates calculations, although such data should be corrected in the statistics breaking down the location of the ultimate investors.

Second, foreign investment often changes hands through international mergers and acquisitions, for example when a Chinese company acquires a German company which has operations in Hungary. According to Szijjártó, 12 of the 16 Chinese companies active in Hungary came here through acquiring German, French and American assets. Such transactions might take time to show up in the data. On the other hand, these cases do not lead to new inflows of capital into Hungary, and as such, they do not have a direct economic or financial effect.

Eastern winds – blowing from the West

Apart from the gap between rhetoric and data, there are more fundamental flaws in Szijjártó’s and Orbán’s theory: ‘Eastern’ investment does not necessarily reduce Hungary’s reliance on Western markets; and Western investment often contributes to raising Hungarian exports to Asian economies.

The reasons are fairly simple. Asian investors usually choose to invest in Hungary either to produce goods for Western European markets, or to serve as a supplier for European production networks in the electronics and the auto industry. Hence, goods produced by Eastern companies in Hungary end up being exported to the EU, deepening the reliance of the Hungarian economy on Western demand.

On the other hand, Western investors are more likely to export their Hungarian production to East Asia. The best example is the German auto industry, which has considerable production bases in Hungary through Audi and Daimler, and accounts for a large share of Hungarian exports to Asian economies.

Another important flaw in the government’s rhetoric is that Eastern investment does not appear to be more productive than Western one. According to a recent study by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on investment by companies from emerging economies in Hungary, most of Eastern FDI is concentrated in lower value-added manufacturing, and research and development activities by emerging investors are scarce. They are also unlikely to use local suppliers and tend to work with their global partners, reducing the likelihood of positive spill-overs for Hungarian firms.

While Szijjártó often proclaims that Hungary is winning the race for Eastern investment, the nationality of the investor appear to hardly matters for the development of the Hungarian economy at large.

Race to the bottom

In spite of this, the foreign minister remains well-regarded among businesspeople for his efforts in courting investment according to reports in the Hungarian press. In all likelihood, this has less to do with his captivating speeches, and more with the government’s generosity when it comes to foreign investors.

An important form of this generosity is government funding for greenfield investment in manufacturing. Szijjártó has announced five such Chinese projects in Hungary last year, with a combined value of 330 million euros. The government offered a total of 64 million euros in grants for these projects, in effect assuming a fifth of the project costs. This is hardly a new phenomenon: according to data compiled by K-Monitor, an NGO, the government spent over a billion euros in grants for foreign investors since 2010.

Hungary’s allure as an investment destination is further elevated by low taxes and low wages. The Hungarian corporate tax rate, at 9 per cent, is the lowest in the EU and among the lowest in the world, while larger foreign investors routinely receive further tax breaks. Unit labor costs are the third lowest in the EU; while the Hungarian currency, the forint lost over one fifth of its value vis-a-vis the euro since 2010, further lowering the cost of doing business here.

This sort of development strategy, when a country tries to lure investment by keeping taxes and wages low, is not a Hungarian specialty, but is well-known among development economists as the ‘race to the bottom’. According to its critics, such a strategy is ill-suited for a middle income country aspiring to catch up to developed economies: such places might be better served by raising productivity through investment in education and training and research and development, while providing a sound business and regulatory environment for local companies to flourish.

The translation was produced in cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.